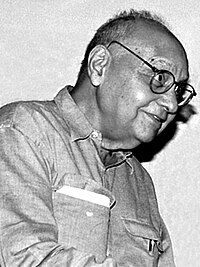

Aditya Prakash (architect)

Aditya Prakash | |

|---|---|

Aditya Prakash | |

| Born | Aditya Prakash 10 March 1924 |

| Died | 12 August 2008 (aged 84) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Indian Institute of Architects Gold Medal |

| Buildings | Tagore Theatre |

| Projects | Chandigarh Capital Project (1952-63), Punjab Agricultural University (1963-68), Chandigarh College of Architecture (1968-82) |

Aditya Prakash ([ɑːd̪it̪jə pr̩ːkɑːɕ];10 March 1924, Muzaffarnagar – 12 August 2008 in Ratlam), was an architect, painter, academic and published author. He belonged to the first generation of Indian Modernists closely associated with Chandigarh and the developmentalist practices of postcolonial India under Jawaharlal Nehru. He designed over 60 buildings all in north India. His paintings are held in private collections worldwide. His architecture and art adhered strictly to modernist principles. As an academic, he was one of the earliest Indian champions of sustainable urbanism. He published two books[1] and several papers on this topic.[2] His archives are held at the Canadian Centre for Architecture at Montreal, Canada. Phantom hands has released a limited collection of his chairs.

Early life

[edit]Prakash began studying architecture at the Delhi Polytechnic (now School of Planning and Architecture) in 1945. In the middle of his course, India's independence forced the English faculty leading the Polytechnic to return to England. At their suggestion, Prakash also moved to London in August 1947 and began to attend evening classes in architecture at the London Polytechnic (now Bartlett), while working with W. W. Woods. After becoming an A.R.I.B.A. in 1951, Prakash moved to Glasgow where he briefly worked and studied art at the Glasgow School of Art, before joining the Chandigarh Capital Project team as Junior Architect on 1 November 1952.[3]

The Chandigarh Capital Project Team

[edit]The Chandigarh team was headed by Pierre Jeanneret, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, under Le Corbusier's overall leadership.[4] The European were supported by an Indian staff of about 60 people. Jeanneret, Fry and Drew were the 'Senior Architects', and Le Corbusier had the title of 'Architectural Advisor'. There were nine Indian 'Junior Architects' and 'Junior Town Planners'. These were M. N. Sharma, A.R. Prabhawalkar, B. P Mathur, Piloo Moody, U.E.Chowdhary, J. L. Malhotra, J.S. Dethe, N.S. Lamba, M. S. Randhawa, R.R.Handa and Aditya Prakash.[5] P.L. Verma was the Chief Engineer, and P.N. Thapar (ICS) was the Chief Administrator of the Project.

According to Aditya Prakash the Capital Project Office was strictly hierarchical, but one in which there was an "open environment" where projects were "explored in their own right". There was a steady atmosphere of research which allowed Prakash to make his own observations which were welcomed by Le Corbusier, even if they stood to potentially challenge him.[6] Prakash explained: "Le Corbusier wanted to show a modern democratic India, and he succeeds by using equal elements to create a rippling, beautiful rhythm. He was rather brash and impatient – he treated us like uninitiated children – but he helped us to realize our own country."[7]

Working with Le Corbusier

[edit]Initially Prakash worked under Jane Drew on the design of the General Hospital and some of the housing of Chandigarh. After that he was given his own design jobs beginning with the District Courts in Sector 17. Conducted under the supervision of Pierre Jeanneret, this project transformed Prakash's design approach prompting him to rethinking architecture and urbanism as a "system". On the design of the Tagore Theatre, Pierre Jeanneret preferred Prakash's design over his own. Prakash felt indebted to Jeanneret for his large-heartedness and humility.[8]

In 1952 Aditya Prakash was assigned to work with Le Corbusier on the design of the School of Art. The process of designing this building with Le Corbusier, especially the rhythm of the piers and the section, was a formative experience in Aditya Prakash's career.[9]

Death

[edit]Prakash died on a train in Ratlam, India, on his way to perform in a play called Zindagi Retire Nahi Hoti.[2]

Personal life

[edit]Aditya Prakash is survived by his wife Savitri Prakash and three children. His son, Vikramaditya Prakash is a notable architectural historian and a scholar at the University of Washington, Seattle.[10] The Aditya Prakash Foundation is based in Chandigarh with a central focus on advancing the understanding of the heritage of Modern Architecture. It is maintained and run by the family and has also been involved in many academic projects related to Chandigarh.[11]

Career

[edit]Prakash worked in the Chandigarh Capital Project Office from 1952 to 1963. During this time he designed several public buildings in Chandigarh, including the District Courts Building in Sector 17, the Jang Garh (Marriage Hall) in Sector 23, the Indo Swiss Training Centre in Sector 30, the Government of India Textbook Press in Industrial Area Phase – 1, The Central Craft Institute in Sector 11, The Tagore Theatre in Sector 18, the Chandigarh College of Architecture in Sector 12, the Architecture "Corbu" Hostel in Sector 12 and the Behl House in Sector 18.

He was also responsible for creating the Frame Control of Chandigarh.[12]

One of Aditya Prakash's key designs was that of the Chandigarh College of Architecture (CCA) which was based on the design of Le Corbusier's Chandigarh College of Art. The budget allocated to CCA was smaller than that for the College of Art. To meet the reduced budget, Prakash decided to scale down the whole building. To do this he had to study Le Corbusier's Modulor, and he created a new 'Indian Modulor' adjusting the original dimensions to fit the Indian brick size.[13] Prakash was closely associated with the design of theatres in Chandigarh. He designed the basic forms of Chandigarh's KC Theatre, Neelam Theatre and Jagat Cinema. His most significant project in Chandigarh was the Tagore Theatre which he designed in 1961 for the centenary of an Indian poet and philosopher Dr. Rabindranath Tagore.[2] This building was designed on strict functionalist lines focused on the interior spaces and their acoustic and visual order. The Tagore Theatre became involved in controversy when it was completely gutted and made into an auditorium by another local architect.[14]

From 1963 Aditya Prakash moved to Ludhiana to design the new Punjab Agricultural University. Agricultural universities "that formed the academic core of this transnational transfer of knowledge". During this time he became very interested in architectural photography and acquired a Rolliflex TLR and an Argus C3 to photograph his buildings under construction. Here the square frame of the Rolliflex frames the views and the rectangle of the Argus directs the eye out towards the landscape.[15]

In 1968, Aditya Prakash returned to Chandigarh as the Principal of the Chandigarh College of Architecture. Early in the 1970s Prakash became an ardent champion of sustainable architecture and urbanism, as what he called 'self-sustaining settlements'. He published several articles and wrote a critique of Chandigarh planning under this title. He also studied the villages surrounding Chandigarh[16] and the informal sector of the city, particularly the 'rehris' or mobile carts.[17]

After retiring from CCA in 1982, Aditya Prakash opened his own private design practise under the name of Arcon Architects, which designed several projects in North India, including a housing complex for the Reserve Bank of India in Chandigarh, Milkfed Milkplants, Rohtak and several administrative buildings for the Agricultural University in Rohtak.[18]

Aditya Prakash's archive was acquired by the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal in 2020.

One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash written by Vikramaditya Prakash was published by Mapin Publishing in 2021. This book was awarded a grant by the Graham Foundation.

Aditya Prakash exhibited his art in several galleries all over India, including the Taj Art Gallery in Mumbai. His work was included as a part of the 2022The Project of Independence exhibition at MoMA Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the 2024 Tropical Modernism exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

In 2023 Phantom Hands released a limited edition of chairs designed by him known as the AP Collection.

Ideas

[edit]- Frame Control : Aditya Prakash designed the visual character for the city by developing frame controls. This "strategy manifests itself through the 'frame' as the organizing element of the city, producing an intersection of gridlines that are superimposed onto the various scales that comprise the public realm". "The building frame scale is regulated by Chandigarh's architectural controls, which are broken into four main categories. Along the V2 streets and in the commercial city center, a system of architectural and construction controls were placed on all buildings. Residential and commercial structures along the V4 market streets are regulated by full architectural controls. Residential plots up to 10 marla in size are governed by frame controls concerning the façade. Schematic controls are applied to special purpose buildings like petrol pumps and cinemas that do not fall under other categories."[19]

- Self-Sustaining Urbanism – Aditya Prakash described the planning in Chandigarh as "escapist" and championed the idea of self-sustaining cities with "extensive recycling, mixed-use developments, stimulation of the informal sector, integration of agriculture and animal husbandry into the urban system, and rigorous separation of motorised and all forms of non-motorised traffic".[15]

- Rehris or the Mobile Shops – These are informal markets and mobile shops that Prakash strongly advocated to be included in the design of the city.[17]

- Linear city – The design proposal for Haryana was one where Prakash sought to empower the pedestrians by proposing to raise the vehicular transit by about 10 to 12 feet above the main road network. In his opinion, that would give the pedestrian and the non-motorized vehicles the necessary relief in an otherwise vehicle intense route. The central part of the sector was important to him as he envisioned a completely self-sustaining city. He commented: "It is important for a city to be self-sustaining in terms of free air, water and the basic necessities like food. All the waste materials of the city can come to this particular area to get recycled, even excess water for that matter…. The informal sector can also be utilized for animal husbandry to a lesser degree."[20]

References

[edit]- ^ Prakash, Aditya Reflections on Chandigarh Navyug Traders, New Delhi, 1983, and Prakash, Aditya Chandigarh – a presentation in free verse Marg Publications, Bombay, 1975

- ^ a b c "In memory of Aditya Prakash". Domusweb.it. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Aditya Prakash, 85, a Prominent Indian Architect, Dies | News | Architectural Record". Archrecord.construction.com. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Aditya Prakash: The Indian Modernist | Shape of Now". Vanibahl.wordpress.com. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Prakash, Vikramaditya Chandigarh's Le Corbusier – The Struggle for Modernity in Postcolonial India University of Washington Press, Seattle, 2002

- ^ "SoundCloud – Hear the world's sounds". soundcloud.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- ^ Tim Mcgirk (3 March 1996). "LE CORBUSIER'S PUNJABI DREAM – Arts & Entertainment". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Khan, Hassan-Uddin, Bienart, Julian, Charles, Chorrea Le Corbusier – Chandigarh and the Modern City, Mapin Publishing, Ahmedabad, 2009

- ^ Prakash, Aditya Working with the Master Inside Outside, Apr/May 1985

- ^ "Vikramaditya Prakash, PhD". Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ APF. "The Aditya Prakash Foundation Blog". Theapfoundation.blogspot.in. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Prakash, Aditya Living Architectural Controls Vol 15. Issue No.1; December 1961. pp. 39–41

- ^ Chalana, Manish, and Tyler S. Sprague. Beyond Le Corbusier and the modernist city: reframing Chandigarh's 'World Heritage’legacy. Planning Perspectives 28, no. 2 (2013): 199–222.

- ^ Not'Tagore Theatre', Please The Hindustan Times (newspaper), Chandigarh, India, September 2008

- ^ a b Site by IF/THEN and Varyable (12 November 2013). "Double Framed | ARCADE | Dialogue on Design". Arcadenw.org. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Prakash, Aditya, Rakesh, Sharma Improving the Chandigarh's Peripheral Villages Ekistics – the Problem and Science of Human Settlements, Community And Home, Vol 39, Number 235, June 1975

- ^ a b Prakash, Aditya. 1974. 'Mobile shops in Chandigarh'. Architects' Year Book, 1974, V.14, pp. 78–84; with Illus., Tables.

- ^ AP Foundation Archives

- ^ Prakash, Vikramaditya Commercialization, Globalization and the Modernist City: The Chandigarh Experience. University of Washington Chandigarh Urban lab, 2011.

- ^ "The Sunday Tribune – Spectrum – Lead Article". Tribuneindia.com. 15 June 2003. Retrieved 6 February 2014.