Green sturgeon

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Green sturgeon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Acipenseriformes |

| Family: | Acipenseridae |

| Genus: | Acipenser |

| Species: | A. medirostris

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acipenser medirostris Ayres, 1854

| |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

The green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) is a species of sturgeon native to the northern Pacific Ocean, from China and Russia to Canada and the United States.

Description

[edit]

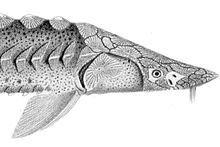

Sturgeons are among the largest and most ancient of ray finned fishes. They are placed, along with paddlefishes and numerous fossil groups, in the infraclass Chondrostei, which also contains the ancestors of all other bony fishes. The sturgeons themselves are not ancestral to modern bony fishes but are a highly specialized and successful offshoot of ancestral chondrosteans, retaining such ancestral features as a heterocercal tail, fin structure, jaw structure, and spiracle. They have replaced a bony skeleton with one of cartilage, and possess a few large bony plates instead of scales. Sturgeons are highly adapted for preying on bottom animals, which they detect with a row of sensitive barbels on the underside of their snouts. They protrude their very long and flexible "lips" to suck up food. Sturgeons are confined to temperate waters of the Northern Hemisphere. Of 25 extant species, only two live in California, the green sturgeon and the white sturgeon (A. transmontanus).[5]

Green sturgeon are similar in appearance to white sturgeon, except the barbels are closer to the mouth than to the tip of the long, narrow snout. The dorsal row of bony plates numbers 8–11, lateral rows, 23–30, and bottom rows, 7–10; there is one large scute behind the dorsal fin as well as behind the anal fin (both lacking in white sturgeon). The scutes also tend to be sharper and more pointed than in white sturgeon. The dorsal fin has 33–36 rays, the anal fin, 22–28. Green sturgeon has a smaller adult size than the white sturgeon.[6]

Green sturgeon can reach 210 cm (7 feet) in length and weigh up to 160 kg (350 pounds).[7]

Diet

[edit]Sturgeon, as benthic feeders, have specialized subterminal mouths that allow them to suction and grind a variety of hard-shelled prey like crustaceans and clams.[8][9] While their primary diet usually consists of mollusks and crustaceans, sturgeons can alter their food sources depending on availability. For instance, juvenile and subadult white sturgeon often consume Corophium amphipods[10] and mysid crustaceans like opossum shrimp, whereas adults feed more on clams and fish eggs. After the invasion of the overbite clam, this clam then became a dominant food source for adult white sturgeon.[11]

Adult green sturgeon feed in estuaries during the summer.[12] Stomachs of green sturgeons caught in Suisun Bay contained Corophium sp. (amphipod), Crago franciscorum (bay shrimp), Neomysis awatchensis (Opossum shrimp) and annelid worms.[13] Stomachs of green sturgeon caught in San Pablo Bay contained Crago franciscorum (bay shrimp), Macoma sp. (clam), Photis californica (amphipod), Corophium sp. (amphipod), Synidotea laticauda (isopod), and unidentified crab and fish.[13] Stomachs of green sturgeons caught in Delta contained Corophium sp. (amphipod), Neomysis awatchensis (Opossum shrimp).[14] Radtke 1966 also reported that while the Asiatic clam (Corbicula fluminea) was abundant throughout the Delta, Suisun Bay and San Pablo Bay, it was not utilized as a food source by green sturgeons. The same study also reported that juvenile green sturgeon primarily consumed Corophium amphipods and some opossum shrimp, showing dietary overlap with juvenile white sturgeon but not with larger ones.[14][15] Both species exhibit dietary flexibility.[16]

Isotope analyses were done by Miller and colleagues in 2024 to study further dietary distinctions. Green sturgeon, due to their more marine-based lifestyle, showed greater reliance on marine food sources compared to white sturgeon. While white sturgeon tended to feed at lower trophic levels in the short periods, both species appeared to feed at the same trophic level over longer periods. This suggested that white sturgeon may shift seasonally to feed on prey like the overbite clam in the San Francisco Bay. Additionally, larger sturgeon of both species showed a greater reliance on marine dietary sources as they grow, though length did not significantly impact the trophic level at which they feed in.[17]

Other interesting aspects

[edit]The green sturgeon, like other sturgeons in the family Acipenseridae, possesses both mechanoreceptors and electroreceptors.[18] The lateral line system in sturgeon comprises two distinct types of sensory receptors: electrosensory ampullary organs (AOs) and mechanosensory neuromasts (NMs). These structures help sturgeon thrive in their aquatic habitats by providing critical information about their surroundings. AOs enable sturgeon to perceive weak electric fields, a capability that is crucial for detecting the electrical signals emitted by prey and predators. These signals include low-frequency membrane potentials and muscle activity, allowing sturgeon to locate food sources or sense nearby threats.[19][20] NMs, on the other hand, are sensitive to water movement and pressure changes around the fish. This mechanosensory function helps sturgeon detect water displacement caused by objects, such as obstacles. The electrosensory and mechanosensory systems enhance sturgeon's ability to forage, avoid danger, and navigate complex environments.[21]

Protected status

[edit]On April 7, 2006, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) issued a final rule listing the Southern distinct population segment (DPS) of North American green sturgeon as a threatened species under the United States Endangered Species Act. Included in the listing is the green sturgeon population spawning in the Sacramento River and living in the Sacramento River, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and the San Francisco Bay Estuary. This threatened determination was based on the reduction of potential spawning habitat, the severe threats to the single remaining spawning population, the inability to alleviate these threats with the conservation measures in place, and the decrease in observed numbers of juvenile Southern DPS green sturgeon collected in the past two decades compared to those collected historically.[22] The southern DPS has been classified with a recovery priority of 5 under the ESA guidelines 55 FR 24296. This classification indicates a moderate extinction risk. Nonetheless, the potential for southern DPS to recover remains significant, particularly if measures are taken to reduce mortality sources and improve the quality and availability of critical spawning and rearing habitats.[23]

Critical habitat for the Southern DPS of green sturgeon was designated under the United States Endangered Species Act on October 9, 2009.

The northern DPS of the green sturgeon (which spawn in the Rogue River, Klamath River, and Umpqua River) is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service Species of Concern. Species of Concern are those species about which the U.S. Government's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Life history and habitat requirements

[edit]

Sturgeons life history strategy seems organized around reducing risks. Sturgeons live a long time, delay maturation to large sizes, and spawn multiple times over their lifespan. The sturgeon's long life span and repeat spawning in multiple years allows them to outlive periodic droughts and environmental catastrophes. The high fecundity that comes with large size allows them to produce large numbers of offspring when suitable spawning conditions occur and to make up for years of poor conditions. Adult green sturgeon do not spawn every year, and only a fraction of the population enters freshwater where they risk greater exposure to catastrophic events. The widespread ocean distribution of green sturgeon ensures that most of the population is dispersed and less vulnerable than they are in estuaries and freshwater streams.

The ecology and life history of green sturgeon have received little study, evidently because of the generally low abundance, limited spawning distribution, and low commercial and sport fishing value of the species.[5] As an anadromous species, green sturgeon enters rivers mainly to spawn. and is more marine than other sturgeon species.[5]

A report commissioned by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) reported in 1995 that for the Klamath River, green sturgeon life history could be divided into three phases: 1) freshwater juveniles (< 3 years old); 2) coastal migrants (3–13 years old for females and 3–9 years for males); and 3) adults (>13 years old for females and >9 years old for males).[24]: 15

Northern DPS green sturgeon migrate up the Klamath River between late February and late July.[5] The spawning period is March–July, with a peak from mid-April to mid-June.[5] Spawning takes place in deep, fast water.[5] Preferred spawning substrate is likely large cobble, but it can range from clean sand to bedrock.[5] Eggs are broadcast and externally fertilized in relatively fast water and probably in depths greater than 3 m.[5] Female green sturgeon produce 59,000–242,000 eggs, about 4.34 mm (171 mils) in diameter.[25][26]

Temperatures of 23–26 °C (73–79 °F) affected cleavage and gastrulation of green sturgeon embryos and all died before hatch.[27] Temperatures of 17.5–22 °C (63.5–71.6 °F) were suboptimal as an increasing number of green sturgeon embryos developed abnormally and hatching success decreased at 20.5–22 °C (68.9–71.6 °F), although the tolerance to these temperatures varied between progenies.[27] The lower temperature limit was not evident from the Van Eenennaam et al. 2005 study, although hatching rate decreased at 11 °C (52 °F) and hatched green sturgeon embryos were shorter, compared to 14 °C (57 °F). The mean total length of hatched green sturgeon embryos decreased with increasing temperature, although their wet and dry weight remained relatively constant.[27] Van Eenennaam et al. 2005 concluded that temperatures 17–18 °C (63–64 °F) may be the upper limit of the thermal optima for green sturgeon embryos. Growth studies on younger juvenile green sturgeon determined that cyclical 19–24 °C (66–75 °F) water temperature was optimal.[28]

Green sturgeon fertilization and hatching rates are 41.2% and 28.0%, compared with 95.4% and 82.1% for the white sturgeon.[29] However, the survival of green sturgeon larvae is very high (93.3%).[29] Female green sturgeon invest a greater amount of their reproductive resources into maternal yolk for nourishment of the embryo, which results in larger larvae.[25] Five-day-old green sturgeon larvae have almost twice the weight of white sturgeon larvae (65 milligrams or 1.00 grain versus 34 milligrams or 0.52 grains) .[25] This greater reserve of maternal yolk and larger larvae could provide an advantage in larval feeding and survival .[25] Compared with other acipenserids, green sturgeon larvae appear more robust and easier to rear.[25] Juveniles continue to grow rapidly, reaching 300 mm (12 in) in 1 year and over 600 mm (24 in) within 2–3 years for the Klamath River.[24] Juveniles spend from 1–4 years in fresh and estuarine waters and disperse into salt water at lengths of 300–750 mm (12–30 in).[24]

A conceptual model of early behavior and migration of green sturgeon early life intervals based on the Kynard et al. 2005 study follows: Females deposit eggs at sites with large rocks and moderate or eddy water flow that keeps the large, dense, poorly adhesive eggs from drifting, so eggs sink deep within the rocks. CH2M Hill (2002) assumed that hatchling green sturgeon embryos drift downstream like hatchling white sturgeon embryos. This was incorrect. Hatchling green sturgeon embryos seek nearby cover, and remain under rocks, unlike white sturgeon which drift downstream as embryos (i.e. newly hatched green sturgeon do not exhibit pelagic behavior like newly hatched white sturgeon).[29] After about 9 days fish develop into larvae and initiate exogenous foraging up- and downstream on the bottom (they do not swim up into the water column, unlike white sturgeon). After a day or so, larvae initiate a downstream dispersion migration that lasts about 12 days (peak, 5 days). At the age of ten days, when exogenous foraging begins, green sturgeons are 19 to 29 mm (0.75 to 1.14 in) in length (mean 24 mm or 0.94 in).[29] At the age of 15 to 21 days, green sturgeon are 30 mm (1.2 in) or greater in length.[29] At the age of 45 days, metamorphosis is complete and green sturgeon are 70 to 80 mm (3.1 in) in length.[29] All migration and foraging during the migration period is nocturnal, unlike white sturgeon. During the first 10 months of life, green sturgeon are the most nocturnal of any North American sturgeon yet studied, and this was the case for all life intervals during any activity (migration, foraging, or wintering). Post-migrant larvae are benthic, foraging up- and downstream diurnally with a nocturnal activity peak. Foraging larvae select open habitat, not structure habitat, but continue to use cover in the day. When larvae develop into juveniles, there is no change in response to bright habitat, and no preference or avoidance of bright habitat. In the fall, juveniles migrate downstream mostly at night to wintering sites, ceasing migration at 7–8 °C (45–46 °F). During winter, juveniles select low light habitat, likely deep pools with some rock structure. Wintering juveniles forage actively at night between dusk and dawn and are inactive during the day, seeking the darkest available habitat.

For the Klamath River green sturgeon, an average length of 1.0 m (3 ft 3 in) is attained in 10 years, 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) by age 15, and 2.0 m (6 ft 7 in) by 25 years of age.[30] The largest reported green sturgeon weighed about 159 kg (351 lb) and was 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) in length.[30] The largest green sturgeon have been aged at 42 years, but this is probably an underestimate, and maximum ages of 60–70 years or more are likely.[5]

Little is known about green sturgeon feeding at sea, but it is clear they behave quite differently than white sturgeon.[31] Green sturgeons are probably found in all open Oregon estuaries, with a lot of movement in and out of estuaries and up and down the coast.[12]

Conservation

[edit]Several conservation efforts have been implemented to protect the Southern Distinct Population Segment (sDPS) of green sturgeon, addressing key factors that threaten the species.

Commercial fisheries have been prohibited in the Columbia River and Willapa Bay since 2001. Harvest of green sturgeon in California has been prohibited since March 2007. Beginning in March 2010 and to protect green sturgeon on their spawning grounds, the Sacramento River sturgeon fishery was closed year-round between the Keswick Dam and Hwy 162 bridge (approximately 90 miles or 140 km).[citation needed] The prohibition of green sturgeon retention in both commercial and recreational fisheries in the US and Canada has been a significant step in reducing overexploitation.

The decommissioning of the Red Bluff Diversion Dam and the introduction of conservation measures under the ESA 4(d) rule have further protected their critical habitats. California has enacted strict regulations, including year-round bans on sturgeon fishing in key river sections, restrictions on tackle, and increased fines for poaching. Oregon and Washington have also increased monitoring of incidental green sturgeon capture.

Several restoration projects have been completed in California's Central Valley that might have potential benefits for green sturgeon. These projects include barrier modifications, wetland habitat restoration, and fish screening to prevent entrainment. Although these efforts are primarily aimed at protecting salmonids, they offer benefits to sturgeon. For example, the removal of the Red Bluff Diversion Dam has clearly improved fish passage for the species. However, there is still a lack of screening criteria specific to green sturgeon, and the overall benefits of these measures remain unclear.

Efforts to prevent the entrainment of green sturgeon in water diversions have included salvage operations at facilities such as the Tracy Fish Collection Facility and the Skinner Delta Fish Protective Facility. Although the number of green sturgeon salvaged is generally low, these actions help protect individuals from harm.[32]

Threats

[edit]Altered Water Flow: Water flow alterations caused by impoundments and diversions affect migration, spawning, and habitat conditions. These changes impact juvenile and adult sturgeon in several key areas, including the San Francisco Bay Delta Estuary and Columbia River Estuary. High spring flows are crucial for successful spawning,[33] and their reduction due to water management poses threats.

Altered Prey Base: Non-native species and climate change significantly disrupt the sturgeon's prey base. Contaminants and invasive species in estuaries alter food resources, and changes in salinity due to climate change further degrade prey availability, threatening both juvenile and adult sturgeons.

Altered Water Temperature: Impoundments and climate change result in altered water temperatures, impacting the sturgeon's reproductive success and larval development.

Contaminants: Agricultural runoff, urban development, and industrial discharges expose green sturgeons to harmful chemicals like mercury, PCBs, and pesticides, impacting their growth and reproductive abilities. Bioaccumulation of these toxins through their prey also poses severe long-term health risks.

Sediment and Turbidity Changes: Impoundments and dams reduce sediment delivery to estuaries, impacting feeding grounds. The reduction in turbidity also increases predation risks. Research is needed to fully understand these impacts on green sturgeon survival.

Migration Barriers: Dams, barriers caused by impoundments, and other structures block the natural migration routes, reducing access to spawning areas. Notable barriers include the Anderson Cottonwood Irrigation District Dam, Keswick and Shasta Dams, and Daguerre Point Dams, which prevent green sturgeons from reaching historical spawning grounds. Bypass systems like Yolo and Sutter further complicate migration.[34]

Water Depth Modification: Sediment buildup from sources like urban runoff and agriculture or caused by removal of riparian and human activities reduces the depth of pools needed by sturgeon for spawning in the Sacramento River Basin. Impoundments limit natural scouring events, reducing pool depth and habitat quality. This poses a significant threat to adult sturgeon and impacts younger stages by altering water turbidity and substrate. Research and monitoring are crucial to assess the full impact.

Loss of Wetland Function: Invasive species, such as Spartina alterniflora and Egeria densa, may disrupt wetland functions in feeding estuaries like Willapa Bay and the San Francisco Bay Delta Estuary. These invasions reduce prey availability and degrade water quality, posing a high threat to adult and sub-adult sturgeon. Further research is needed to determine the exact extent of these impacts.[35][36][37]

Overutilization: Although no current threats from overutilization are considered High or Very High, past fishing activities have impacted the population. Currently, there is no green sturgeon fisheries, except for the Yurok Tribe. Incidental catch and poaching remain moderate threats in some areas.

Predation: High predation rates affect eggs, larvae, and juveniles due to various fish species like Sacramento sucker (native) and striped bass (non-native). Marine mammals such as sea lions and sharks [38] are also potential predators for adults and subadults.

Inadequacy of Regulatory Mechanisms: Current regulations are considered inadequate to address many of the threats facing green sturgeon, such as migration barriers, water quality, and habitat protection. Key areas needing regulatory improvement include sturgeon passage, flow regulation, pollution control, and enforcement of poaching laws. Additionally, regulations concerning invasive species, agricultural diversions, and oil spill response need strengthening.

Entrainment: Green sturgeon are highly vulnerable to entrainment in water diversions.[39] Current screening methods may be inadequate to prevent sturgeon from being trapped and injured.

Electromagnetic Fields, competition, and disease are all potential threats to the green sturgeon. Offshore and near-shore energy projects pose potential risks due to electromagnetic fields, habitat competition from both native and non-native species is a high risk, and poor water quality and potential disease transmission from native and non-native species pose a significant future threat. More research is needed to assess the full impact for these topics.[40]

Current and historical distribution

[edit]

The green sturgeon is the most widely distributed member of the sturgeon family Acipenseridae, and is also the most marine-oriented of the sturgeon species. Green sturgeon are known to range in nearshore marine waters from Mexico to the Bering Sea, with a general tendency to head North after their out-migration from freshwater.[41] They are commonly observed in bays and estuaries along the western coast of North America, with particularly large concentrations entering the Columbia River estuary, Willapa Bay, and Grays Harbor during the late summer.[5][41] While there is some bias associated with recovery of tagged fish through commercial fishing, the pattern of a northern migration is supported by the large concentration of green sturgeon in the Columbia River estuary, Willapa Bay, and Grays Harbor, which peaks in August.[41]

Prehistoric fish distributions have been mapped by Gobalet et al. 2004 based on bones at Native American archaeological sites. Data were reported on dozens of sites throughout California and summarized by county. Sturgeon remains were observed in 12 counties, all in the Central Valley. Observations were concentrated at San Francisco Bay and Sacramento-San Joaquin and delta sites (Contra Costa, Alameda, San Francisco, Marin, Napa, San Mateo and Santa Cruz counties). Historical 18th-century accounts report the aboriginal gillnetting and use of tule balsa watercraft for the capture of sturgeon, and fishing weirs were also likely employed on bay tidal flats.[42] Most sturgeons were unidentified species but green sturgeons were specifically identified from Contra Costa and Marin County sites. Sturgeon remains (unidentified species) were also identified from lower Sacramento River counties (Sacramento, Yolo, Colusa, Glenn, and Butte counties). No sturgeon remains were found in samples from the upper Sacramento River although other fish species including salmonids were reported in those areas.

Green sturgeons which spawn in the Rogue River, Klamath River, and Umpqua River are the Northern DPS green sturgeon, while the green sturgeons which spawn in the Sacramento River system are Southern DPS green sturgeon.[41] Both the Northern DPS green sturgeon and Southern DPS green sturgeon occur in large numbers in the Columbia River estuary, Willapa Bay, and Grays Harbor, Washington.[41]

A number of presumed spawning populations (Eel River and South Fork Trinity River) have been lost in the past 25–30 years.[5] Moyle 1976 reported green sturgeon spawning in the Mad River, but does not mention the Mad River in 2002. Scott and Crossman 1973 reported potential spawning in the Fraser River in Canada, but Moyle 2002 reported that there was no evidence of green sturgeon spawning in Canada or Alaska. Green and white sturgeon enter the Feather River system annually and spawning of green sturgeon was documented for the first time in 2011.[43] No current use by sturgeon of Sacramento River tributaries, other than the Feather River system, has been reported. [44][5] No evidence was found to indicate that green sturgeons were historically present, are currently present, or were historically present and have been extirpated from the San Joaquin River upstream from the Delta.[44] There is no evidence of green sturgeon spawning in the Columbia River or other rivers in Washington. ,[5][12][45] In contrast to those studies, samples from green sturgeon collected in the Columbia River suggest the existence of one or more spawning populations in addition to the Sacramento system, Klamath, and Rogue populations, suggesting not all spawning populations have been identified.[46]

Individual Southern DPS green sturgeon tagged by the California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) in the San Francisco Estuary have been recaptured off Santa Cruz, California; in Winchester Bay on the southern Oregon coast; at the mouth of the Columbia River; and in Gray's Harbor, Washington.[30][5] Most tags for Southern DPS green sturgeon tagged in the San Francisco Estuary have been returned from outside that estuary.[5] Green sturgeons remain present in all documented historic habitats and ranges in Oregon.[45]

White and green sturgeon juveniles, subadults, and adults are widely distributed in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and estuary areas including San Pablo.[44] White sturgeon historically ranged into upper portions of the Sacramento system including the Pit River and a substantial number were trapped in and above Lake Shasta when Shasta Dam was closed in 1944 and successfully reproduced until the early 1960s.[44] Landlocked white sturgeon populations have been widely observed in the Columbia and Fraser systems but no landlocked green sturgeon populations have ever been documented in any river system,[44] indicating that green sturgeon likely did not historically spawn in the upper reaches of rivers prior to the construction of large dams as NMFS 2005 has assumed.

Taxonomy

[edit]According to recent genetic data,[47] the differences between the mitogenomes of the green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) and the Sakhalin sturgeon (Acipenser mikadoi) to correspond to the variability at the intraspecific level. The time since the divergence of the green sturgeon and the Sakhalin sturgeon may be approximately 160,000 years.

References

[edit]- ^ Moser, M. (2022). "Acipenser medirostris". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T233A97433481. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (2017). "Acipenseridae". FishBase version (02/2017). Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ^ Van Der Laan, Richard; Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ronald (11 November 2014). "Family-group names of Recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (1): 1–230. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3882.1.1. PMID 25543675.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Moyle 2002.

- ^ Grindle et al., 2021

- ^ Dees, L. T. (1961). Sturgeons. U.S. Fish Wildlife Service. pp. 526:1–8.

- ^ Moyle & Cech, Jr., 2003

- ^ Vecsei & Peterson, 2004

- ^ Radtke, 1966

- ^ Zeug et al., 2014

- ^ a b c Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2005a.

- ^ a b Ganssle 1966.

- ^ a b Radtke 1966.

- ^ Zeug et al., 2014

- ^ Miller et al., 2024

- ^ Miller et al., 2024

- ^ Gibbs & Northcutt, 2004

- ^ Crampton, 2019

- ^ Teeter et al., 1980

- ^ Wang et al., 2020

- ^ National Marine Fisheries Service 2006.

- ^ NMFS, 2018

- ^ a b c Nakamoto & Kisanuki 1995.

- ^ a b c d e Van Eenennaam et al. 2001, pp. 159–165.

- ^ Van Eenennaam et al. 2006, pp. 151–163.

- ^ Allen et al. 2006, pp. 89–96.

- ^ a b c d e f Deng, Eenennaam & Doroshov 2002.

- ^ a b c U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1993.

- ^ California Department of Fish and Game 2005.

- ^ NMFS, 2018

- ^ Heublein et al. 2017

- ^ Thomas et al. 2013

- ^ Grosholz et al., 2009

- ^ Moser et al., 2017

- ^ Durand et al., 2016

- ^ Huff et al., 2011

- ^ Mussen et al., 2014

- ^ NMFS, 2018

- ^ a b c d e National Marine Fisheries Service 2005.

- ^ Gobalet et al. 2004, pp. 801–833.

- ^ Seesholtz, Manuel & Van Eenennaam 2015, pp. 905–912.

- ^ a b c d e Beamesderfer et al. 2004.

- ^ a b Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 2005b.

- ^ Israel et al. 2004, pp. 922–931.

- ^ Shedko, Sergei (2017-05-04). "The Low Level of Differences between Mitogenomes of the Sakhalin Sturgeon Acipenser mikadoi Hilgendorf, 1892 and the Green Sturgeon A. medirostris Ayeres, 1854 (Acipenseridae) Indicates their Recent Divergence". Russian Journal of Marine Biology. 43 (2): 176–179. Bibcode:2017RuJMB..43..176S. doi:10.1134/S1063074017020080. S2CID 35257523.

Bibliography

[edit]- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Acipenser medirostris". FishBase. February 2009 version.

- Allen, Peter J.; Nicholl, Mary; Cole, Stephanie; Vlazny, Amy; Cech, Joseph J. (2006). "Growth of Larval to Juvenile Green Sturgeon in Elevated Temperature Regimes". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 135 (1): 89–96. Bibcode:2006TrAFS.135...89A. doi:10.1577/T05-020.1. ISSN 0002-8487.

- Beamesderfer, R.; Simpson, M.; Kopp, G.; Inman, J.; Fuller, A.; Demko, D. (2004). Historical and Current Information on Green Sturgeon Occurrence in the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers and Tributaries (PDF) (Report). S.P. Cramer and Associates, Inc.

- California Department of Fish and Game (2005). White Sturgeon Population Estimate (Report) – via Email from Marty Gingras, Senior Biologist Supervisor, California Department of Fish and Game.

- CH2M Hill, Inc. 2002. Environmental Impact Statement/Environmental Impact Report for Fish Passage Improvement Project at the Red Bluff Diversion Dam. Prepared by CH2MHill, Inc. for the Tehama-Colusa Canal Authority and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

- Crampton, W. G. (2019). Electroreception, electrogenesis and electric signal evolution. Journal of Fish Biology, 95(1), 92–134.

- Deng, X.; Eenennaam, J.P. Van; Doroshov, S.I. (2002). Comparison of Early Life Stages and Growth of Green and White Sturgeon (PDF). American Fisheries Society Symposium. pp. 237–248.

- Durand, J., Fleenor, W., McElreath, R., Santos, M. J., & Moyle, P. (2016). Physical controls on the distribution of the submersed aquatic weed Egeria densa in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta and implications for habitat restoration. San Francisco Estuary and Watershed Science, 14(1).

- Gobalet, Kenneth W.; Schulz, Peter D.; Wake, Thomas A.; Siefkin, Nelson (2004). "Archaeological Perspectives on Native American Fisheries of California, with Emphasis on Steelhead and Salmon". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 133 (4): 801–833. Bibcode:2004TrAFS.133..801G. doi:10.1577/T02-084.1. ISSN 0002-8487.

- Ganssle, D. (1966). "Fishes and Decapods of San Pablo and Suisun Bays.". In D.W. Kelley (ed.). Ecological Studies of the Sacramento San Joaquin Estuary: Part I; Zooplankton, Zoobenthos, and Fishes of San Pablo and Suisun Bays, Zooplankton and Zoobenthos of the Delta. Fish Bulletin. Vol. 133. California Department of Fish and Game.

- Grindle, E. D., Rick, T. C., Dagtas, N. D., Austin, R. M., Wellman, H. P., Gobalet, K., & Hofman, C. A. (2021). Green or white? Morphology, ancient DNA, and the identification of archaeological North American Pacific Coast sturgeon. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 36, 102887.

- Gibbs, M. A., & Northcutt, R. G. (2004). Development of the lateral line system in the shovelnose sturgeon. Brain Behavior and Evolution, 64(2), 70–84.

- Grosholz, E. D., Levin, L. A., Tyler, A. C., & Neira, C. (2009). Changes in community structure and ecosystem function following Spartina alterniflora invasion of Pacific estuaries. ) Anthropogenic Modification of North American Salt Marshes. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

- Heublein, J. C., Bellmer, R. J., Chase, R. D., Doukakis, P., Gingras, M., Hampton, D., ... & Stuart, J. S. (2017). Life history and current monitoring inventory of San Francisco estuary sturgeon.

- Huff, D. D., Lindley, S. T., Rankin, P. S., & Mora, E. A. (2011). Green sturgeon physical habitat use in the coastal Pacific Ocean. PLoS One, 6(9), e25156.

- Israel, Joshua A.; Cordes, Jan F.; Blumberg, Marc A.; May, Bernie (2004). "Geographic Patterns of Genetic Differentiation among Collections of Green Sturgeon". North American Journal of Fisheries Management. 24 (3): 922–931. Bibcode:2004NAJFM..24..922I. doi:10.1577/M03-085.1. ISSN 0275-5947.

- Kynard, Boyd; Parker, Erika; Parker, Timothy (2005). "Behavior of early life intervals of Klamath River green sturgeon, Acipenser medirostris, with a note on body color". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 72 (1): 85–97. Bibcode:2005EnvBF..72...85K. doi:10.1007/s10641-004-6584-0. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Miller, E. A., Singer, G. P., Peterson, M. L., Webb, M., & Klimley, A. P. (2024). Comparative stable isotope analyses of green sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) and white sturgeon (A. transmontanus) in the San Francisco estuary. Journal of Fish Biology, 104(1), 240–251.

- Moyle, P.B. (2002). Inland Fishes of California. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 106–113.

- Moyle, P. B., & Cech, J. J. (2000). Fishes: an introduction to ichthyology.

- Moser, M. L., Patten, K., Corbett, S. C., Feist, B. E., & Lindley, S. T. (2017). Abundance and distribution of sturgeon feeding pits in a Washington estuary. Environmental Biology of Fishes, 100, 597–609.

- Mussen, T. D., Cocherell, D., Poletto, J. B., Reardon, J. S., Hockett, Z., Ercan, A., ... & Fangue, N. A. (2014). Unscreened water-diversion pipes pose an entrainment risk to the threatened green sturgeon, Acipenser medirostris. PloS one, 9(1), e86321.

- Nakamoto, Rodney J.; Kisanuki, Tom T. (1995). Age and Growth of Klamath River Green Sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris) (PDF) (Report). Yreka, California: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Klamath River Fishery Resource Office. Retrieved 13 September 2024 – via California State Water Resources Control Board.

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (2005a). "Chapter 6". Wildfish.[permanent dead link]

- Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (2005b). Oregon Native Fish Status Report.

- National Marine Fisheries Service (2005-04-06). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Proposed Threatened Status for Southern Distinct Population Segment of North American Green Sturgeon". Federal Register.

- National Marine Fisheries Service (2006-04-07). "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Threatened Status for Southern Distinct Population Segment of North American Green Sturgeon". Federal Register.

- National Marine Fisheries Service. (2018). Final recovery plan for the Southern Distinct Population Segment of North American Green Sturgeon (Acipenser medirostris). NOAA Fisheries.

- Seesholtz, Alicia M.; Manuel, Matthew J.; Van Eenennaam, Joel P. (2015). "First documented spawning and associated habitat conditions for green sturgeon in the Feather River, California". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 98 (3): 905–912. Bibcode:2015EnvBF..98..905S. doi:10.1007/s10641-014-0325-9. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Radtke, L.D. (1966). "Distribution of Smelt, Juvenile Sturgeon, and Starry Flounder in the Sacramento San Joaquin Delta with observations on Food of Sturgeon". In D.W. Kelley (ed.). Ecological Studies of the Sacramento San Joaquin Estuary: Part II; Fishes of the Delta (PDF). Fish Bulletin. Vol. 133. California Department of Fish and Game. pp. 115–129.

- Teeter, J. H., Szamier, R. B., & Bennett, M. V. L. (1980). Ampullary electroreceptors in the sturgeon Scaphirhynchus platorynchus (Rafinesque). Journal of Comparative Physiology, 138, 213–223.

- Thomas, M. J., Peterson, M. L., Friedenberg, N., Van Eenennaam, J. P., Johnson, J. R., Hoover, J. J., & Klimley, A. P. (2013). Stranding of spawning run green sturgeon in the Sacramento River: post-rescue movements and potential population-level effects. North American Journal of Fisheries Management, 33(2), 287–297.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1993). Framework: For the Management and Conservation of Paddlefish and Sturgeon Species in the United States (Report). Division of Fish Hatcheries, Washington DC.

- Van Eenennaam, Joel P.; Webb, Molly A. H.; Deng, Xin; Doroshov, Serge I.; Mayfield, Ryan B.; Cech, Joseph J.; Hillemeier, David C.; Willson, Thomas E. (2001). "Artificial Spawning and Larval Rearing of Klamath River Green Sturgeon". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 130 (1): 159–165. Bibcode:2001TrAFS.130..159V. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(2001)130<0159:ASALRO>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0002-8487.

- Van Eenennaam, Joel P.; Linares-Casenave, Javier; Deng, Xin; Doroshov, Serge I. (2005). "Effect of incubation temperature on green sturgeon embryos, Acipenser medirostris". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 72 (2): 145–154. Bibcode:2005EnvBF..72..145V. doi:10.1007/s10641-004-8758-1. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Van Eenennaam, Joel P.; Linares, Javier; Doroshov, Serge I.; Hillemeier, David C.; Willson, Thomas E.; Nova, Arnold A. (2006). "Reproductive Conditions of the Klamath River Green Sturgeon". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 135 (1): 151–163. Bibcode:2006TrAFS.135..151V. doi:10.1577/T05-030.1. ISSN 0002-8487.

- Vecsei, P., & Peterson, D. (2004). Sturgeon ecomorphology: a descriptive approach. In Sturgeons and paddlefish of North America (pp. 103–133). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Wang, J., Lu, C., Zhao, Y., Tang, Z., Song, J., & Fan, C. (2020). Transcriptome profiles of sturgeon lateral line electroreceptor and mechanoreceptor during regeneration. BMC genomics, 21, 1–14.

- Zeug, S. C., Brodsky, A., Kogut, N., Stewart, A. R., & Merz, J. E. (2014). Ancient fish and recent invaders: white sturgeon Acipenser transmontanus diet response to invasive-species-mediated changes in a benthic prey assemblage. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 514, 163–174.