Military history of Iran

The military history of Iran has been relatively well-documented, with thousands of years' worth of recorded history. Largely credited to its historically unchanged geographical and geopolitical condition, the modern-day Islamic Republic of Iran (historically known as Persia) has had a long and checkered military culture and history; ranging from triumphant and unchallenged ancient military supremacy, affording effective superpower status for its time; to a series of near-catastrophic defeats (beginning with the destruction of Elam), most notably including the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon as well as the Asiatic nomadic tribes at the northeastern boundary of the lands traditionally home to the Iranian peoples.

Elam (3500–539 BCE)

[edit]Medes (678–549 BCE)

[edit]Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE)

[edit]-

A golden chariot made during Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE).

-

The Achaemenid Empire at its greatest extent.

-

Right: Persian soldier. Left: Median soldier.

-

Persian warriors.

The Achaemenid Empire (559–330 BCE) was the first of the Persian Empires to rule over significant portions of Greater Iran. The empire possessed a "national army" of roughly 120.000-150.000 troops, plus several tens of thousands of troops from their allies.

The Persian army was divided into regiments of a thousand each, called hazarabam. Ten hazarabams formed a haivarabam, or division. The best known haivarabam were the Immortals, the King's personal guard division. The smallest unit was the ten-man dathaba. Ten dathabas formed the hundred man sataba.

The royal army used a system of color uniforms to identify different units. A large variety of colors were used, some of the most common being yellow, purple, and blue. However, this system was probably limited to native Persian troops and was not used for their numerous allies.

The usual tactic employed by the Persians in the early period of the empire, was to form a shield wall that archers could fire over. These troops (called sparabara, or shield-bearers) were equipped with a large rectangular wicker shield called a spara, and armed with a short spear, measuring around six feet long.

Though equipped and trained to conduct shock action (hand-to-hand combat with spears, axes and swords), this was a secondary capability and the Persians preferred to maintain their distance from the enemy in order to defeat him with superior missile-power. The bow was the preferred missile-weapon of the Persians. At maximum rate of fire a sparabara haivarabam of 10,000 men could launch approximately 100,000 arrows in a single minute and maintain this rate for a number of minutes. Typically the Persian cavalry would open the battle by harassing the enemy with hit and run attacks – shooting arrows and throwing small javelins – while the Persian sparabara formed up their battle-array. Then the Persian cavalry would move aside and attempt to harass the flanks of the enemy. Defending against the Persian cavalry required the enemy infantry to congregate in dense static formations, which were ideal targets for the Persian archers. Even heavily armoured infantry like the Greek hoplites would suffer heavy casualties in such conditions. Enemy infantry formations that scattered to reduce casualties from the dense volleys of Persian arrows, were exposed to a close-in shock assault by the Persian cavalry. Torn by the dilemma between exposure to a gradual attrition by the arrows or to being overwhelmed by a cavalry charge on their flanks, most armies faced by the Persians succumbed.

The major weaknesses of the typical Persian tactics were that proper application of these tactics required: a) A wide battlefield composed of fairly flat and expansive terrain that would not hinder the rapid movement of massed horses and where the cavalry could conduct proper flanking maneuvers. b) Good coordination between the cavalry, infantry, and missile units. c) An enemy inferior in mobility. d) An enemy lacking a combined-arms military.

Most Persian failures can be attributed to one or more of these requirements not being met. Thus, the Scythians evaded the Persian army time and again because they were all mounted and conducted only hit-and-run raids on the Persians; at Marathon the Athenians deployed on a rocky mountainous slope and only descended to the plain after the Persian cavalry had reboarded their transport-ships – charging through the arrow-shower to conduct close-combat with spears and swords – a form of combat for which the Athenians were better equipped and better trained; at Thermopylae the Greek army deliberately deployed in a location that negated the Persians ability to use cavalry and missile-power, again forcing them to fight only head-on in close-combat and was forced to retreat only after the Persians were informed of a bypass that enabled them to circumvent this defensive position to defeat the Spartans; at Plataea the Persian attack was poorly coordinated and defeated piecemeal; Alexander the Great's Macedonian army that invaded the Persian empire was composed of a variety of infantry and cavalry types (combined-arms approach) that enabled it, together with Alexander's superior tactical generalship, to negate the Persian capabilities and, once again, force them to fight close-combat.

Seleucid Empire (312 BCE–63 BCE)

[edit]The Seleucid Empire was a Hellenistic successor state of Alexander the Great's dominion, including central Anatolia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, Persia, Turkmenistan, Pamir and the Indus valley.

Parthian Empire (247 BCE–224 CE)

[edit]

Parthia was an Iranian civilization situated in the northeastern part of modern Iran, but at the height of its power, the Parthian dynasty covered all of Iran proper, as well as Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iraq, Georgia, eastern Turkey, eastern Syria, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Kuwait, the Persian Gulf, the coast of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and the UAE.[1]

The Parthian empire was led by the Arsacid dynasty, led by the Parni, a confederation of Scythians which reunited and ruled over the Iranian plateau, after defeating and disposing the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire, beginning in the late 3rd century BCE, and intermittently controlled Mesopotamia between 150 BCE and 224 CE. It was the third native dynasty of ancient Iran (after the Median and the Achaemenid dynasties). Parthia was the arch-enemy of the Roman Empire for nearly three centuries.[2]

After the Scythian-Parni nomads had settled in Parthia and built a small independent kingdom, they rose to power under king Mithridates the Great (171–138 BCE).[3] The power of the early Parthian empire seems to have been overestimated by some ancient historians, who could not clearly separate the powerful later empire from its more humble obscure origins. The end of this long-lived empire came in 224 AD, when the empire was loosely organized and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassals, the Persians of the Sassanid dynasty.

Sassanid Empire (224–651)

[edit]

The birth of the Sassanid army dates back to the rise of Ardashir I (r. 226–241), the founder of the Sasanian dynasty, to the throne. Ardashir aimed at the revival of the Persian Empire, and to further this aim, he reformed the military by forming a standing army which was under his personal command and whose officers were separate from satraps, local princes and nobility. He restored the Achaemenid military organizations, retained the Parthian cavalry model, and employed new types of armour and siege warfare techniques. This was the beginning for a military system which served him and his successors for over 400 years, during which the Sassanid Empire was, along with the Roman Empire and later the East Roman Empire, one of the two superpowers of late antiquity in Western Eurasia. The Sassanid army protected Eranshahr ("the realm of Iran") from the East against the incursions of central Asiatic nomads like the Hephthalites, Turks, while in the west it was engaged in a recurrent struggle against its rival, the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire, setting on forth the conflict that had started since the time of their predecessors, the Parthians, and would end after around 720 years, making it the longest conflict in human history.[4][5]

Arab-Muslim conquest (633–654)

[edit]

The Islamic conquest of Persia (633–656) led to the end of the Sassanid Empire and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost, but were to a great extent absorbed by the new Islamic polity.

Most Muslim historians have long offered the idea that Persia, on the verge of the Arab invasion, was a society in decline and decay and thus it embraced the invading Arab armies with open arms. This view is not widely accepted however. Some authors have for example used mostly Arab sources to illustrate that "contrary to the claims, Iranians in fact fought long and hard against the invading Arabs."[6] This view further more holds that once politically conquered, the Persians began engaging in a culture war of resistance and succeeded in forcing their own ways on the victorious Arabs.[7][8]

Tahirid dynasty (821–873)

[edit]Although nominally subject to the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, the Tahirid rulers were effectively independent. The dynasty was founded by Tahir ibn Husayn, a leading general in the service of the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun. Tahir's military victories were rewarded with the gift of lands in the east of Persia, which were subsequently extended by his successors as far as the borders of India.

The Tahirid dynasty is considered to be the first independent dynasty from the Abbasid Caliphate established in Khorasan. They were overthrown by the Saffarid dynasty, who annexed Khorasan to their own empire in eastern Persia.

Alavid dynasties (864–928)

[edit]The Alavids or Alavians were a Shia emirate based in Mazandaran of Iran. They were descendants of the second Shi'a Imam (Imam Hasan ibn Ali) and brought Islam to the south Caspian Sea region of Iran. Their reign was ended when they were defeated by the Samanid Empire in 928 AD. After their defeat some of the soldiers and generals of the Alavids joined the Samanid dynasty. Mardavij the son of Ziar was one of the generals that joined the Samanids. He later founded the Ziyarid dynasty. Ali, Hassan and Ahmad the sons of Buye [bu:je] (that were founders of the Buyid (Buwayhid) dynasty) were also among generals of the Alavid dynasty who joined the Samanid army.

Saffarid dynasty (861–1003)

[edit]The Saffarid dynasty ruled a short-lived empire in Sistan, which is a historical region now in southeastern Iran and southwestern Afghanistan. Their rule was between 861 and 1003.[9]

The Saffarid capital was Zaranj (now in Afghanistan). The dynasty was founded by – and took its name from – Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar, a man of humble origins who rose from an obscure beginning as a coppersmith (saffar) to become a warlord. He seized control of the Seistan region, conquering all of Afghanistan, modern-day eastern Iran, and parts of Pakistan. Using their capital (Zaranj) as base for an aggressive expansion eastwards and westwards, they overthrew the Tahirid dynasty and annexed Khorasan in 873. By the time of Ya'qub's death, he had conquered Kabul Valley, Sindh, Tocharistan, Makran (Baluchistan), Kerman, Fars, Khorasan, and nearly reaching Baghdad but then suffered defeat.[10]

|

| History of Greater Iran |

|---|

The Saffarid empire did not last long after Ya'qub's death. His brother and successor Amr bin Laith was defeated in a battle with the Samanids in 900. Amr bin Laith was forced to surrender most of their territories to the new rulers. The Saffarids were subsequently confined to their heartland of Sistan, with their role reduced to that of vassals of the Samanids and their successors.

Samanid Empire (819–999)

[edit]The Samanids (819–999)[11] were a Persian dynasty in Central Asia and Greater Khorasan, named after its founder Saman Khuda who converted to Sunni Islam[12] despite being from Zoroastrian theocratic nobility. It was among the first native Iranian dynasties in Greater Iran and Central Asia after the Arab conquest and the collapse of the Sassanid Persian empire.

Ziyarid dynasty (931–1090)

[edit]The Ziyarids, also spelled Zeyarids (زیاریان or آل زیار), were an Iranian dynasty that ruled in the Caspian sea provinces of Gorgan and Mazandaran from 930 to 1090 (also known as Tabaristan). The founder of the dynasty was Mardavij (from 930 to 935), who took advantage of a rebellion in the Samanid army of Iran to seize power in northern Iran. He soon expanded his domains and captured the cities of Hamadan and Isfahan.

Buyid dynasty (934–1062)

[edit]The Buyid dynasty[13] were a Shī‘ah Persian[14][15] dynasty that originated from Daylaman in Gilan. They founded a confederation that controlled most of modern-day Iran and Iraq in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Ghaznavid dynasty (977–1186)

[edit]The Ghaznavids were a Muslim dynasty of Turkic slave origin[16] which existed from 975 to 1187 and ruled much of Persia, Transoxania, and the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[17]

The dynasty was founded by Sebuktigin upon his succession to rule of territories centered around the city of Ghazni from his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, a break-away ex-general of the Samanid sultans.[18] Sebuktigin's son, Shah Mahmoud, expanded the empire in the region that stretched from the Oxus river to the Indus Valley and the Indian Ocean; and in the west it reached Rey and Hamadan. Under the reign of Mas'ud I it experienced major territorial losses. It lost its western territories to the Seljuqs in the Battle of Dandanaqan resulting in a restriction of its holdings to what is now Afghanistan, as well as Balochistan and the Punjab. In 1151, Sultan Bahram Shah lost Ghazni to Ala al-Din Husayn of Ghur and the capital was moved to Lahore until its subsequent capture by the Ghurids in 1186.

Seljuk Empire (1037–1194)

[edit]

The Seljuqs were a Turco-Persian[20][21] Sunni Muslim dynasty that ruled parts of Central Asia and the Middle East from the 11th to 14th centuries. They set up an empire, the Great Seljuq Empire, which at its height stretched from Anatolia through Persia and which was the target of the First Crusade. The dynasty had its origins in the Turcoman tribal confederations of Central Asia and marked the beginning of Turkic power in the Middle East. After arriving in Persia, the Seljuqs adopted the Persian culture[22] and are regarded as the cultural ancestors of the Western Turks – the present-day inhabitants of Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Turkmenistan.

Khwarazmian Empire (1077–1231)

[edit]

The Khwarezmian dynasty, also known as Khwarezmids or Khwarezm Shahs was a Persianate Sunni Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin.[23][24]

They ruled Greater Iran in the High Middle Ages, in the period of about 1077 to 1231, first as vassals of the Seljuqs[citation needed], Kara-Khitan,[25] and later as independent rulers, up until the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. The dynasty was founded by Anush Tigin Gharchai, a former slave of the Seljuq sultans, who was appointed the governor of Khwarezm. His son, Qutb ud-Dīn Muhammad I, became the first hereditary Shah of Khwarezm.[26]

Ilkhanate (1256–1335)

[edit]

The Ilkhanate was a Mongol khanate established in Persia in the 13th century, considered a part of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanate was based, originally, on Genghis Khan's campaigns in the Khwarezmid Empire in 1219–1224, and founded by Genghis's grandson, Hulagu, in what territories which today comprise most of Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and western Pakistan. The Ilkhanate initially embraced many religions, but was particularly sympathetic to Buddhism and Christianity, and sought a Franco-Mongol alliance with the Crusaders in order to conquer Palestine. Later Ilkhanate rulers, beginning with Ghazan in 1295, embraced Islam.

Muzaffarid dynasty (1314–1393)

[edit]Chobanid dynasty (1338–1357)

[edit]Jalayirid Sultanate (1335–1432)

[edit]The Jalayirids (آل جلایر) were a Mongol descendant dynasty which ruled over Iraq and western Persia[27] after the breakup of the Mongol Khanate of Persia (or Ilkhanate) in the 1330s.

The Jalayirid sultanate lasted about fifty years, until disrupted by Tamerlane's conquests and the revolts of the "Black sheep Turks" or Kara Koyunlu. After Tamerlane's death in 1405, there was a brief unsuccessful attempt to re-establish the Jalayirid sultanate and Jalayirid sultanate was ended by Kara Koyunlu in 1432.

Timurid Empire (1370–1507)

[edit]

The Timurids were a Central Asian Sunni Muslim dynasty of originally Turko-Mongol descent whose empire included the whole of Central Asia, Iran, modern Afghanistan, as well as large parts of Pakistan, India, Mesopotamia, Anatolia and the Caucasus. It was founded by the militant conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) in the 14th century.

In the 16th century, Timurid prince Babur, the ruler of Ferghana, invaded India and founded the Mughal Empire, which ruled most of the Indian subcontinent until its decline after Aurangzeb in the early 18th century, and was formally dissolved by the British Empire after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Qara Qoyunlu Turkomans (1374–1468)

[edit]Aq Qoyunlu Turkomans (1378–1503)

[edit]

Safavid Empire (1501–1736)

[edit]

The Safavid rulers of Persia, like the Mamluks of Egypt, viewed firearms with distaste, and at first made little attempt to adopt them into their armed forces. Like the Mamluks they were taught the error of their ways by the powerful Ottoman armies. Unlike the Mamluks they lived to apply the lessons they had learnt on the battlefield. In the course of the sixteenth century, but still more in the seventeenth, the shahs of Iran took steps to acquire handguns and artillery pieces and to re-equip their forces with them. Initially, the principal sources of these weapons appears to have been Venice, Portugal, and England.

Despite their initial reluctance, the Persians very rapidly acquired the art of making and using handguns. A Venetian envoy, Vincenzo di Alessandri, in a report presented to the Council of Ten on 24 September 1572, observes:

"They used for arms, swords, lances, arquebuses, which all the soldiers carry and use; their arms are also superior and better tempered than those of any other nation. The barrels of the arquebuses are generally six spans long, and carry a ball little less than three ounces in weight. They use them with such facility that it does not hinder them drawing their bows nor handling their swords, keeping the latter hung at their saddle bows till occasion requires them. The arquebus is then put away behind the back so that one weapon does not impede the use of the other."

This picture of the Persian horseman, equipped for almost simultaneous use of the bow, sword, and firearm, aptly symbolized the dramatic and complexity of the scale of changes that the Persian Military was undergoing. While the use of personal firearms was becoming commonplace, the use of field artillery was limited and remained on the whole ineffective.

Shah Abbas (1587–1629) was instrumental in bringing about a 'modern' gunpowder era in the Persian army. Following the Ottoman Army model that had impressed him in combat the Shah set about to build his new army. He was much helped by two English brothers, Anthony and Robert Shirley, who went to Iran in 1598 with twenty-six followers and remained in the Persian service for a number of years. The brothers helped organize the army into an officer-paid and well-trained standing army similar to a European model. It was organized along three divisions: Ghilman ('crown servants or slaves' conscripted from hundreds of thousands of ethnic Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians), Tofongchis (musketeers), and Topchis (artillery-men)

Shah Abbas's new model army was massively successful and allowed him to re-unite parts of Greater Iran and expand his nations territories at a time of great external pressure and conflict.

The Safavid era also saw the mass integration of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Caucasians, notably Circassians, Georgians, Armenians, and other peoples of the Caucasus in Persian society, starting with the era of Shah Tahmasp I, and which would last all the way till the Qajar era. Originally only deployed for being fierce warriors and having beautiful women, this policy was notably significantly expanded under Shah Abbas I, who would use them as a complete new layer in Persian society, most notably to crush the power of the feudal Qizilbash. Under Abbas' own reign, some 200,000 Georgians, tens of thousands of Circassians, and 300,000 Armenians were deported to Iran. Many of them were, as above mentioned, put in the ghilman corps, but the larger masses were deployed in the regular armies, the civil administration, royal household, but also as labourers, farmers, and craftsmen. Many notorious Iranian generals and commanders were of Caucasian ancestry. Many of their descendants linger forth in Iran as the Iranian Georgians, Iranian Circassians, and Iranian Armenians (see Peoples of the Caucasus in Iran), and many millions of Iranians are estimated to have Caucasian ancestry as a following of this.

Upon the fall of the Safavid dynasty Persia entered into a period of uncertainty. The previously highly organized military fragmented and the pieces were left for the following dynasties to collect.

Afsharid dynasty (1736–1796)

[edit]Following the decline of the Safavid state a brilliant general by the name of Nader Shah took the reins of the country. This period and the centuries following it were characterised by the rise in Russian power to Iran's north.

Following Nader Shah, many of the other leaders of the Afsharid dynasty were weak and the state they had built quickly gave way to the Qajars. As the control of the country de-centralised with the collapse of Nader Shah's rule, many of the peripheral territories of the Empire gained independence and only paid token homage to the Persian State. One of the branches of service to benefit most from Nader's reforms was by far the artillery. During the reign of the Safavid dynasty gunpowder weapons were used to a relatively limited extent and were certainly not to be considered central to the Safavid military machine.[28] Although most of Nader's military campaigns were conducted with an aggressive speed of advance which brought up difficulties in keeping up the heavy guns with the army's rapid marches, Nader placed great emphasis on enhancing his artillery units.

The main centres of Persian armament production were Amol, Kermanshah, Isfahan, Merv. These military factories achieved high levels of production and managed to equip the army with good quality cannon. However mobile workshops allowed for Nader to maintain his strategic mobility whilst preserving versatility in the deployment of heavy siege cannon when required.

Zand dynasty (1751–1794)

[edit]Qajar Empire (1789–1925)

[edit]

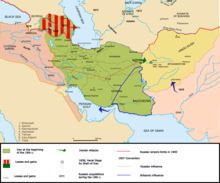

The second half of the 18th century saw a new dynasty take hold in Iran. The new Qajar dynasty was founded on slaughter and plunder of Iranians, particularly Zoroasterian Iranians. The Qajars, under their dynasty founder, Agha Mohammad Khan plundered and slaughtered the aristocrats of the previous Zand dynasty. Following this, Agha Mohammad Khan was determined to regain all lost territories following the death of Nadir Shah. First on his was the Caucasus, and most notably Georgia. Iran had intermittently ruled most of the Caucasus since 1555, since the early days of the Safavid dynasty, but while Iran was in chaos and tumult, many of their subjects had declared themselves quasi-independent, or in the case of the Georgians, had plotted an alliance with the Russian Empire by the Treaty of Georgievsk. Agha Mohammad Khan, furious at his Georgian subjects, starting his expedition with 60,000 cavalry under his command, defeated the Russian garrisons stationed there and drove them back out of the entire Caucasus in several important battles, and completely sacked Tbilisi, and carried of some 15,000 captives back to Iran. Following the capture of Georgia, Agha Mohammad Khan was murdered by two of his servants who feared they would be executed. The rise of the Qajars was very closely timed with Catherine the Great's order to invade Iran once again. During the Persian expedition of 1796, Russian troops crossed the Aras river and invaded parts of Azarbaijan and Gilan, while they also moved to Lankaran with the aim of occupying Rasht again. His nephew and successor, Fath Ali Shah, after several successful campaigns of his own against the Afshars, with the help of Minister of War Mirza Assadolah Khan and Minister Amir Kabir created a new strong army, based on the latest European models, for the newly chosen Crown-Prince Abbas Mirza.

This period marked a serious decline in Persia's power and thus its military prowess. From here onwards the Qajar dynasty would face great difficulty in its efforts, due to the international policies mapped out by some western great powers and not Persia herself. Persia's efforts would also be weakened due to continual economic, political, and military pressure from outside of the country (see the Great Game), and social and political pressures from within would make matters worse.

With the consolidation of the Treaty of Georgievsk, Russia annexed eastern Georgia and Dagestan in 1801, dethroning the Bagrationi dynasty. In 1803, Fath Ali Shah was determined to get Georgia and Dagestan back, and fearing Russia would march on more south towards Persia and the Ottoman Empire too, declared war on Russia. While starting with the upper hand, Russians were ultimately victorious in the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813). From the beginning, Russian troops had a great advantage over the Persians as they possessed much modern artillery, the use of which had never sunk into the Persian army since the Safavid dynasty three centuries earlier. Nevertheless, the Persian army under the command of Abbas Mirza managed to win several victories over the Russians. Iran's inability to develop modern artillery during the preceding, and the Qajar, dynasty resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813. This marked a turning point in the Qajar attitude towards the military.

Mining copper in Azerbaijan, Set Khan Astvatsatourian provided a catalyst for the reformation of the Persian military, as previously all large quantities of copper for cannon smelting had been imported from the Ottoman Empire. Set Khan's development of domestic artillery production not only helped further the Azerbaijan-based military reform, but also contributed to Abbas Mirza's realization of the critical importance of the use of foreign techniques and military technology in the Persian military.[29] Abbas Mirza sent a large number of Persians to England to study Western military technology and at the same time he invited British officers to Persia to train the Persian forces under his command.

The army's transformation was phenomenal as can be seen from the Battle of Erzeroum (1821) where the new army routed an Ottoman army. This resulted in the Treaty of Erzurum whereby the Ottoman Empire acknowledged the existing frontier between the two empires. These efforts to continue the modernisation of the army through the training of officers in Europe continued until the end of the Qajar dynasty. With the exceptions of Russian and British militaries, the Qajar army of the time was unquestionably the most powerful in the region.

With his new army, Abbas Mirza invaded Russia in 1826. While in the first year of the war Persia managed to regain almost all lost territories, reaching almost Georgia and Dagestan too, the Persian army ultimately proved no match for the significantly larger and equally capable Russian army. The following Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 crippled Persia through the ceding of much of Persia's northern territories and the payment of a colossal war indemnity. The scale of the damage done to Persia through the treaty was so severe that The Persian Army and state would not regain its former strength till the rise and creation of the Soviet Union and the latter's cancellation of the economic elements of the treaty as 'tsarist imperialistic policies'. After these periods of Russo-Persian Wars, Russian influence in Persia rose significantly too.

The reigns of both Mohammad Shah and Nasser al-Din Shah also saw attempts by Persia to bring the city of Herat, occupied by the Afghans, again under Persian rule. In this, though the Afghans were no match for the Persian Army, the Persians were not successful, this time because of British intervention as part of the Great Game (See papers by Waibel and Esandari Qajar within the Qajar Studies source). Russia backed the Persian attacks, using Persia as a 'cat's paw' for expansion of its own interests. Britain feared the seizure of Herat would leave a route to attack British India controlled by a power friendly to Russia, and threatened Persia with closure of the trade of the Persian Gulf. When Persia abandoned its designs on Herat, the British no longer felt India was threatened. This, combined with growing Persian fears about Russian designs on their own country, led to the later period of Anglo-Persian military co-operation.

Ultimately, under the Qajars, Persia was shaped into its modern form. Initially, under the reign of Agha Mohammad Khan Persia won back many of its lost territories, notably in the Caucasus, only to be lost again through a series of bitter wars with Russia. In the west the Qajars effectively stopped encroachment of their Ottoman arch-rival in the Ottoman–Persian War (1821–1823) and in the east the situation remained fluid.

Foreign powers had an increasing influence over time including on the Qajar army.[30][31] Nonetheless irregular forces, such as tribal cavalry, remained a major element into the late nineteenth century.[32]

In 1878, the arsenals in Tehran and Tabriz contained 10,000 Chassepot rifles, 40,000 Tabatière rifles and from 20,000 to 30,000 of other firearms. The Tabatières were captured by the Germans in 1870 and then sold to the Shah on his travel to Europe for 21 francs each. The artillery included around 500 smooth-bore and 60 rifled guns, all made of brass, the latter of which had been rifled in Iran on the Belgian system.[33] Lord Curzon however, reports the number of Chassepot rifles at 20,000 and the Tabatière rifles at 30,000 in 1892.[34]

The Russian Empire established the Persian Cossack Brigade in 1879, a force which was led by Russian officers and served as a vehicle for influence in Iran.[35][36] The brigade gave the Russian Empire influence over the modernization of the Qajar army. This was especially pronounced because the Persian monarchy's legitimacy was predicated on an image of military prowess, first Turkic and then European-influenced.[37][30]

During the Persian Constitutional Revolution, Qajar Iran was invaded by Russia to support the Shah, with British diplomatic support. This included the Russian occupation of Tabriz.[31]

By the 1910s, the Qajar Iran was decentralised to the extent that foreign powers sought to bolster the central authority of the Qajars by providing military aid. It was viewed as a process of defensive modernisation; however, this also led to internal colonisation.[38]

The Iranian Gendarmerie was founded in 1911 with the assistance of Sweden.[39][38] The involvement of a neutral country was seen to avoid "Great Game" rivalry between Russia and Britain, as well as avoid siding with any particular alliance (in the prelude to World War I). Persian administrators thought the reforms could strengthen the country against foreign influences. The Swedish-influenced police had some success in building up Persian police in centralizing the country.[39] After 1915, Russia and Britain demanded the recall of the Swedish advisers. Some Swedish officers left, while others sided with the Germans and Ottomans in their intervention in Persia. The remainder of the Gendarmerie was named amniya after a patrol unit that existed in the early Qajar dynasty.[39]

The number of Russian officers in the Cossack Brigade would increase over time. Britain also sent sepoys to reinforce the Brigade. After the start of the Russian Revolution, many tsarist supporters remained in Persia as members of the Cossack Brigade rather than fighting for or against the Soviet Union.[36]

The British formed the South Persia Rifles in 1916, which was initially separate from the Persian army until 1921.[40]

In 1921, the Russian-officered Persian Cossack Brigade was merged with the gendarmerie and other forces, and would become supported by the British.[41]

Ultimately, through Qajar rule the military institution was further developed and a capable and regionally superior military force was developed, which saw limited service during the Persian Campaign of the First World War.

At the end of the Qajar dynasty in 1925, Reza Shah's Pahlavi army would include members of the gendarmerie, Cossacks, and former members of the South Persia Rifles.[36]

Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

When the Pahlavi dynasty came to power, the Qajar dynasty was already weak from years of war with Russia. The standing Persian army was almost non-existent. The new king Reza Shah Pahlavi, was quick to develop a new military, the Imperial Iranian Army. In part, this involved sending hundreds of officers to European and American military academies. It also involved having foreigners re-train the existing army within Iran. In this period a national air force (the Imperial Iranian Air Force) was established and the foundation for a new navy (the Imperial Iranian Navy) was laid. Other armed forces of the time included the Imperial Guard and the Iranian Gendarmerie.

Following Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the United Kingdom (UK) and the Soviet Union became allies. Both saw the newly opened Trans-Iranian Railroad as a strategic route to transport supplies from the Persian Gulf to the Soviet Union and were concerned that Reza Shah was sympathetic to the Axis powers, despite his declaration of neutrality. In August 1941, the UK and the Soviet Union invaded Iran and deposed him in favor of his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Following the end of the Second World War, both countries withdrew their military forces from Iran.

Following a number of clashes in April 1969, relations with Iraq fell into a steep decline, mainly due to a dispute over the Shatt al-Arab (called Arvand Rud in Persian) waterway in the 1937 Algiers Accord. Iran abrogated the 1937 accord and demanded a renegotiation which ended completely in its favor. Furthermore, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi embarked on an unprecedented modernisation program of the Iranian armed forces. In many cases Iran was being supplied with advanced weaponry even before it was supplied to the armed forces of the countries that developed it. During this period of strength Iran protected its interests militarily in the region: in Oman, the Dhofar Rebellion was crushed. In November 1971, Iranian forces seized control of three uninhabited but strategic islands at the mouth of the Persian Gulf; Abu Musa and the Tunb islands.

In the 1960s as Iran began to prosper from oil revenues, and diplomatic relations were established with many countries, Iran began to expand its military. In the 1960s it purchased Canada's fleet of 90 Canadair Sabre fighters armed with AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles. These aircraft were later sold to Pakistan.[42]

In the early 1970s the Iranian economy saw record years of growth thanks to booming oil prices. By 1976, the Iranian GDP was the largest in the Greater Middle East. The Shah (king) of Iran set about modernising the Iranian military, intent on purchasing billions of dollars worth of the most sophisticated and advanced equipment and weaponry from countries like the United States and the United Kingdom.[43]

Iran's purchases from the United States prior to the Iranian Revolution in 1979 included: 79 F-14 Tomcats, 455 M60 Patton tanks, 225 McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II fighter planes, including 16 of the RF-4E reconnaissance variant; 166 Northrop F-5 fighters including 15 of the RF-5A reconnaissance variant; 6 Lockheed P-3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft and two decommissioned and modernised American destroyers, (USS Zellars and USS Stormes). As of 1976 Iran had acquired 500 M109 howitzers from the United States, 52 MIM-23 Hawk anti aircraft batteries with over 2000 missiles, over 2500 AGM-65 Maverick air to ground missiles and over 10,000 BGM-71 TOW missiles. Furthermore, Iran ordered hundreds of helicopters from the United States, notably 202 Bell AH-1J Sea Cobras, 100 Boeing CH-47C Chinooks and 287 Bell 214 helicopters.[44]

Iran's purchases from the United Kingdom prior to the 1979 revolution included 1 decommissioned and modernized British destroyer (HMS Sluys), 4 British-built frigates (the Alvand class,) and a vast array of missiles such as the Rapier and Seacat systems. Additionally Iran purchased several dozen SR.N6 hovercraft, 250 FV101 Scorpion light tanks and 790 Chieftain tanks.[45][46]

Iran also notably received much of its armored equipment from the Soviet Union. These deals were usually bartered using cheap oil and natural gas from the Iranian side in exchange for Soviet expertise, training and equipment. In regards to military equipment Iran ordered ZSU-23-4 artillery vehicles, BTR 300 BTR-60s along with 270 BTR-50s and 300 BM-21 Grad multiple rocket launchers.[47][48]

The Imperial Iranian Navy maintained the largest fleet of operational attack hovercraft in the world. These hovercraft were obtained from various British and American companies and were later retrofitted with weaponry. In having this fleet the Iranian navy would be able to patrol shallow areas or the gulf and avoid minefields.[49]

The Iranian military never received many of the orders placed in the late 1970s due to the Iranian Revolution occurring in February 1979. The list below seeks to highlight some of the major orders that were placed prior the Iranian revolution but were never completed or delivered.

In the late 1970s, Iran accelerated its orders from the United States in an attempt to outpace British, French and Chinese military orders. The Shah of Iran believed that Iran was destined to become a world super power, proudly led by one of the strongest militaries in the world. By 1972, the Imperial Iranian Armed Forces had a total of 298,300 personnel, excluding the nation’s police. A year later, in 1973, around 59% of Iranian males were fit for service.[50] In regards to the Imperial Iranian Air Force, in 1976 Iran ordered 300 F-16 Fighting Falcons and a further 71 Grumman F-14 Tomcats on top of the 79 that had arrived. All of these orders were due in 1980. In September 1976 Iran formally requested the purchase of 250 F/A-18 Hornets, however this order would not have arrived until 1985. In addition to this, in late 1977 Iran ordered 7 Boeing Boeing E-3 Sentry AWACS command and control aircraft and 12 Boeing 707 jets designed to refuel planes in midair.[51][52][53]

A massive order was made by the Iranian government in an attempt to modernize the Iranian Imperial Navy and give it the capability to patrol the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. The Navy had placed an order for 4 Kidd-class destroyers armed with Standard missiles, Harpoon missiles, Phalanx CIWSs and Mark 46 torpedoes; as well as 3 used and retrofitted Tang-class submarines (these were transferred rather than sold to Iran from the US Navy) armed with Harpoon missiles. In addition the navy sought to acquire 39 Lockheed P-3 Orion maritime patrol planes for ocean surveillance and anti-submarine warfare.[54][55] Unlike the air force, the Imperial Iranian Navy did not solely rely on American armaments and used a wide variety of suppliers. From Germany, Iran ordered 6 diesel type 209 submarines due to arrive in 1980 intended to protect Iran in the Indian Ocean.[56] From Italy, Iran ordered 6 Lupo-class frigates, capable of anti-submarine warfare and outfitted with Otomat missiles.[57] In 1978 Iran ordered 8 Kortenaer-class frigates from the Netherlands, each one armed with Mk. 46 torpedoes, Harpoon missiles and Sea Sparrow anti-aircraft missiles. In the same year Iran sought to order a further four Bremen-class frigates (similar in design to the Kortenaer class).[58] Iran had entered discussions with Great Britain as early as the late 1960s to purchase a nuclear powered aircraft carrier that would give Iran amphibious attack capabilities in the Indian Ocean. While initially interested in purchasing one CVA-01 aircraft carrier, which was later on cancelled by the British, Iran expressed interest in the Invincible-class aircraft carriers.[59] Talks were in place for Iran to purchase 3 modified versions of these carriers however no official record stands to prove that such an order was placed.[60] From France, Iran ordered 12 La Combattante II type fast attack craft (named the Kaman class) equipped with Harpoon missiles. Of this order, approximately 6 were delivered and the subsequent 6 cancelled.

During this same time-frame in the 1970s the Imperial Iranian Army was making several advancements and placing massive orders to keep up with other branches of the military. To reinforce the ground troops Iran ordered 500 M109 howitzers and 455 M60 Patton A3 tanks from the United States. The largest order was placed with the United Kingdom for 2000 Chieftain tanks, which had been specifically designed for the Imperial Iranian Army.[60] Some other major equipment on order included hundreds of Soviet BMP-1s outfitted with anti-tank missiles.[46] In addition the Iranians sought to strengthen their position in the Strait of Hormuz by setting up missile sites in the close vicinity.

When the Carter administration turned down Iran's request for nuclear capable missiles, it turned to Israel. It was working on the Project Flower ballistic missiles with Israel.[61]

In addition to these developments, the government of Iran had begun alongside American and British corporations, the licensed manufacturing of several different types of military equipment. Iran was very active in manufacturing Bell Helicopters, Boeing Helicopters and TOW missiles. Many bases were under construction to house all of the military equipment. Two very notable and large bases were to be built were in Abadan, where a massive infantry unit and air force presence would serve to protect Iran from any Iraqi aggression, while the other in Chabahar was to house a port capable of housing submarines and aircraft carriers which would allow Iran to patrol the Indian Ocean.[60]

At this time Iran was investing over $10bn in the construction of nuclear power stations; 8 locations would be built by the US, 2 by Germany and 2 by France, for its 23,000 MW nuclear project which could produce enough uranium for 500–600 warheads.[62][63]

Iran contributed to United Nations peacekeeping operations. It joined the United Nations Operation in the Congo (ONUC) in the 1960s, and ten years later, Iranian troops joined the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) on the Golan Heights.[citation needed]

Gallery of Pahlavi-era service crests

[edit]-

Imperial Iranian Ministry of War

-

Imperial Iranian Army (IIA)

-

Imperial Iranian Navy (IIN)

-

Imperial Iranian Air Force (IIAF)

Islamic Republic of Iran (1979–present)

[edit]Under Ruhollah Khomeini (1979–1989)

[edit]In 1979, the year of the revolution in which Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been exiled by the shah for 15 years, heightened the rhetoric against the "Great Satan"[64] and focused popular anger on the United States and its embassy in Tehran, the Shah's departure was consummated. The Iranian military thereupon experienced a 60% desertion from its ranks. Following the ideological principles of the Islamic revolution in Iran, the new revolutionary government sought to strengthen its domestic situation by conducting a purge of senior military personnel closely associated with the Pahlavi dynasty. It is still unclear how many were dismissed or executed. The purge encouraged the dictator of Iraq, Saddam Hussein to view Iran as disorganised and weak, leading to the Iran–Iraq War.

The indecisive eight-year Iran-Iraq War (IIW), which began on 22 September 1980 when Iraq invaded Iran, wreaked havoc on the region and the Iranian military. After it expanded into the Persian Gulf, where it led to clashes between the United States Navy and Iran (1987-1988), the IIW ended on 20 August 1988 when both parties accepted a UN-brokered ceasefire.[65][66]

On 26 August 1988, the UN published Security Council Resolution 620 because it was "deeply dismayed" and "profoundly concerned" that Iraq had employed chemical weapons on an indiscriminate basis, and called[67]

upon all States to continue to apply, to establish or to strengthen strict control of the export of chemical products serving for the production of chemical weapons, in particular to parties to a conflict, when it is established or when there is substantial reason to believe that they have used chemical weapons in violation of international obligations.

Under Ali Khamenei (1989–present)

[edit]Following the Iran-Iraq War, an ambitious military rebuilding program was set into motion with the intention to create a fully fledged military industry.[citation needed] Islamic Iran has always striven to foster and develop the nuclear science industry it captured from the Shah. In 2002 George W. Bush tagged Iran with the label Axis of evil, and in 2003, the Proliferation Security Initiative was born. The IAEA became concerned around this time with Iran's potential weaponization of nuclear technology, and that led in 2006 to the formation of the P5+1 consortium, which signed in 2015 with Iran the now-imperilled JCPOA that was designed to prevent nuclear weaponization by Iran.

Regionally, since the Islamic Revolution, Iran has sought to exert its influence by supporting various groups (militarily and politically). It openly supports Hezbollah in Lebanon in order to influence Lebanon and threaten Israel.[citation needed] Various Kurdish groups are also supported as needed in order to maintain control of its Kurdish regions.[citation needed] In neighbouring Afghanistan, Iran supported the Northern Alliance for over a decade against the Taliban, and nearly went to war against the Taliban in 1998.[68]

Under Khamenei, and especially in the decade from 2010, Iran has made no secret of its ambitions as a regional-class power. It was formally excluded from participation in the Iraq War (2003–2011). Its contention with the Saudi Arabia, especially as one of the sponsors of the Houthi rebellion in Yemen, and its military aid to Syria over the course of the Syrian Civil War mark it as a threat to the status quo Pax Americana, under which flourish minor Sunni Emirates along the West coast of the Persian Gulf.

In September 2019, as joint military exercises with Russia and China in the Gulf of Oman and the Indian Ocean were announced, President Rouhani declared to America and the G7 Nations that[69][70]

Your presence has always been a calamity for this region and the farther you go from our region and our nations the more security would come.

In 2021, the regular army had announced that it will launch a satellite into space.[71]

Gallery of Islamic Republic service crests

[edit]-

Ground Force of Iran

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Parthia (2): the empire". Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ Bryce, Trevor (March 2014). Ancient Syria:A Three Thousand Year History. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0199646678. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ George Rawlinson, The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World, 2002, Gorgias Press LLC ISBN 1931956480

- ^ "Sassanids". Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ Kim, Hyun Jin (2013). The Huns, Rome and the birth of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107009066. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ Milani A. Lost Wisdom. 2004 ISBN 0934211906 p. 15

- ^ Mohammad Mohammadi Malayeri, Tarikh-i Farhang-i Iran (Iran's Cultural History). 4 volumes. Tehran. 1982.

- ^ ʻAbd al-Ḥusayn Zarrīnʹkūb (2000). Dū qarn-i sukūt : sarguz̲asht-i ḥavādis̲ va awz̤āʻ-i tārīkhī dar dū qarn-i avval-i Islām (Two Centuries of Silence). Tihrān: Sukhan. OCLC 46632917.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Hatch Dupree, Nancy (1979). "Sites in Perspective". An Historical Guide To Afghanistan.

- ^ Britannica, Saffarid dynasty

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Edition, 2007, "Samanid Dynasty", LINK

- ^ Daniel, Elton L. The History of Iran. p. 74.

- ^ Busse, Heribert (1975), "Iran Under the Buyids", in Frye, R. N., The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, p. 270: "Aleppo remained a buffer between the Buyid empire and Byzantium".

- ^ "BUYIDS". Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Encyclopedia Iranica: "Deylamites"". Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Islamic Central Asia: an anthology of historical sources, Ed. Scott Cameron Levi and Ron Sela, (Indiana University Press, 2010), 83; "The Ghaznavids were a dynasty of Turkic slave-soldiers..."

- ^ C.E. Bosworth: The Ghaznavids. Edinburgh, 1963

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Ghaznavid Dynasty", Online Edition 2007

- ^ Black, Jeremy (2005). The Atlas of World History. American Edition, New York: Covent Garden Books. pp. 65, 228. ISBN 978-0756618612. This map varies from other maps which are slightly different in scope, especially along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 1988), 147.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991)

- ^ John Perry, "The Historical Role of Turkish in Relation to Persian of Iran", Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 5, (2001), pp. 193–200.

- ^ Bosworth in Camb. Hist. of Iran, Vol. V, pp. 66 & 93; B.G. Gafurov & D. Kaushik, "Central Asia: Pre-Historic to Pre-Modern Times"; Delhi, 2005; ISBN 8175412461

- ^ C. E. Bosworth, "Chorasmia ii. In Islamic times" in: Encyclopaedia Iranica (reference to Turkish scholar Kafesoğlu), v, p. 140, Online Edition: "The governors were often Turkish slave commanders of the Saljuqs; one of them was Anūštigin Ḡaṛčaʾī, whose son Qoṭb-al-Dīn Moḥammad began in 490/1097 what became in effect a hereditary and largely independent line of ḵǰᵛārazmšāhs[what language is this?]." (LINK)

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian history, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 44.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Khwarezm-Shah-Dynasty", (LINK)

- ^ The History Files Rulers of Persia

- ^ Rudi Matthee, "Unwalled Cities and Restless Nomads: Firearms and Artillery in Safavid Iran" in Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, ed. Charles Melville (London, 1996)

- ^ Ethnicity, identity, and the development of nationalism in Iran. 2014.

- ^ a b Rabi, Uzi; Ter-Oganov, Nugzar (2009). "The Russian Military Mission and the Birth of the Persian Cossack Brigade: 1879–1894". Iranian Studies. 42 (3): 445–463. doi:10.1080/00210860902907396. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 25597565. S2CID 143812599.

- ^ a b Meyer, Karl E. (10 August 1987). "Opinion | The Editorial Notebook; Persia: The Great Game Goes On". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Rabi, Uzi; Ter-Oganov, Nugzar (2012). "The Military of Qajar Iran: The Features of an Irregular Army from the Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Century". Iranian Studies. 45 (3): 333–354. doi:10.1080/00210862.2011.637776. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 41445213. S2CID 159730844.

- ^ Upton, Emory (1878). The armies of Asia and Europe (First ed.). New York: D. Appleton and Company, 549 and 551 Broadway. p. 91.

- ^ Curzon, George Nathaniel (1892). Persia and the Persian question (First ed.). London: Spottiswoode and co. p. 602.

- ^ Andreeva, Elena (2007). Russia and Iran in the great game : travelogues and Orientalism. London: Routledge. pp. 20, 63–76. ISBN 978-0203962206. OCLC 166422396.

- ^ a b c "Cossack Brigade". Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Deutschmann, Moritz (2013). ""All Rulers are Brothers": Russian Relations with the Iranian Monarchy in the Nineteenth Century". Iranian Studies. 46 (3): 401–413. doi:10.1080/00210862.2012.759334. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 24482848. S2CID 143785614.

- ^ a b "The Swedish-led Gendarmerie in Persia 1911–1916 State Building and Internal Colonization". Sharmin and Bijan Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Iran and Persian Gulf Studies. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Sweden ii. Swedish Officers in Persia, 1911–15". Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ "South Persia Rifles". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Zirinsky, Michael P. (1992). "Imperial Power and Dictatorship: Britain and the Rise of Reza Shah, 1921–1926". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 24 (4): 639–663. doi:10.1017/S0020743800022388. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 164440. S2CID 159878744.

- ^ "Cached".

- ^ Nixon, Kissinger, and the Shah: the origins of Iranian primacy in the Persian Gulf

- ^ history.navy.mil: USS Stormes

2.^ navsource.org USS Zellars

"Thirty minutes to choose your fighter jet: how the Shah of Iran chose the F-14 Tomcat over the F-15 Eagle". The Aviationist. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

"The Imperial Iranian Ground Force." aryamehr.org. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

"IIAF – F-5". www.iiaf.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

"Phantom with Iran". www.joebaugher.com. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

"[2.0] Second-Generation Cobras". www.airvectors.net. Retrieved 10 September 2015. - ^ "HMS Sluys, destroyer". www.naval-history.net. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

Pike, John. "Alvand Class". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 2 September 2015. - ^ a b "The Imperial Iranian Ground Force." aryamehr.org. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ register http://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/trade register.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help)[permanent dead link] - ^ "RECENT TRENDS IN IRANIAN ARMS PROCUREMENT - Department of State". Foreign Relations of the U.S., 1969–1976, Volume E–4, Documents on Iran and Iraq, 1969–1972. May 1972 – via Office of the Historian.

- ^ "WRMEA – Iran's Alarming Military Buildup Transfixes Wary Gulf Neighbors". Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ "Iran" (PDF). National Intelligence Survey: 11 – via CIA.

- ^ "F-16 Air Forces – Cancelled Orders". www.f-16.net. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ McGlinchey, Stephen (2014). US Arms Policies Towards the Shah's Iran. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317697091.

- ^ Tessmer, Arnold L. (1 September 1995). Politics of Compromise: NATO and AWACS. Diane Publishing. ISBN 978-0788121548.

- ^ "DDG-993 KIDD-class – Navy Ships". fas.org. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Pike, John. "Iran Navy Modernization". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ Tan, Andrew T. H. (2014). The Global Arms Trade: A Handbook. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136969546.

- ^ "The ascendance of Iran : a study of the emergence of an assertive Iranian foreign policy and its impact on Iranian-Soviet relations. : Williams, James Harlon;Magnus, Ralph H. : Free Download & Streaming". Internet Archive. 1979. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ^ CIA (23 March 1978). "National Intelligence Daily Cable" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ "The Harrier Aircraft". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 24 April 1975. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ a b c "The Iranian deals | The Guardian BAE investigation | guardian.co.uk". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ Times, Elaine Sciolino, Special to the New York (1 April 1986). "Documents Detail Israeli Missile Deal With the Shah". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nuclear Iran: The Birth of an Atomic State By David Patrikarakos

- ^ "This Page Has Been Deleted or Moved form Iran Map". Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ Moin Khomeini, (2000), p. 220

- ^ "Iran-Iraq UNIMOG Background". United Nations.

- ^ Bardehle, Peter (Spring 1992). "The Role of the United Nations in the Settlement of the Iran-Iraq War, 1980–88". Conflict Quarterly: 36–50.

- ^ "Security Council Resolution 620 (1988) of 26 August 1988". UNHCR.

Deeply dismayed by the missions' conclusions that there had been continued use of chemical weapons in the conflict between Iran and Iraq and that such use against Iranians had become more intense and frequent, Profoundly concerned by the danger of possible use of chemical weapons in the future, Determined to intensify its efforts to end all use of chemical weapons in violation of international obligations now and in the future, 1. Condemns resolutely the use of chemical weapons in the conflict between Iran and Iraq,

- ^ "Iran's gulf of misunderstanding with US". BBC News. 25 September 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Iran plans Gulf exercise with Russia and China". Times Newspapers Limited. 23 September 2019.

- ^ "Iran, Russia and China Plan Joint Naval Drill in Gulf of Oman". The Maritime Executive, LLC. 23 September 2013.

- ^ "ورود ارتش ایران به باشگاه سازندگان ماهواره". Khabar Fori. 31 December 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2006). Arms and Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period. Legat Verlag. ISBN 978-3932942228.

- The Middle East: 2000 Years of History From The Rise of Christianity to the Present Day, Bernard Lewis, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995.

- Qajar Studies: War and Peace in the Qajar Era, Journal of the Qajar Studies Association, London: 2005.

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (March 2009). "Las Técnicas de la Esgrima Persa". Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas (in Spanish). 4 (1): 20–49. doi:10.18002/rama.v4i1.223.

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2009). "Persian Firearms Part One: The Matchlocks". Classic Arms and Militaria. XVI (1): 42–47.

- Moshtagh Khorasani, Manouchehr (2009). "Persian Firearms Part Two: The Flintlock". Classic Arms and Militaria. XVI (2): 22–26.