A Momentary Lapse of Reason

| A Momentary Lapse of Reason | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Original cover[nb 1] | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 7 September 1987 | |||

| Recorded | November 1986 – March 1987 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Progressive rock | |||

| Length | 51:09 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | ||||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from A Momentary Lapse of Reason | ||||

| ||||

A Momentary Lapse of Reason is the thirteenth studio album by the English progressive rock band Pink Floyd, released in the UK on 7 September 1987 by EMI and the following day in the US on Columbia. It was recorded primarily on the converted houseboat Astoria, belonging to the guitarist, David Gilmour.

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was the first Pink Floyd album recorded without the founding member Roger Waters, who departed in 1985. The production was marred by legal fights over the rights to the Pink Floyd name, which were not resolved until several months after release. It also saw the return of the keyboardist and founding member Richard Wright, who was fired by Waters during the recording of The Wall (1979). Wright returned as a session player.[3]

Unlike most of Pink Floyd's preceding studio records, A Momentary Lapse of Reason is not a concept album. It includes writing contributions from outside songwriters, following Gilmour's decision to include material once intended for his third solo album. The album was promoted with three singles: the double A-side "Learning to Fly" / "Terminal Frost", "On the Turning Away", and "One Slip".

A Momentary Lapse of Reason received mixed reviews; some critics praised the production and instrumentation but criticised Gilmour's songwriting, and it was derided by Waters. It reached number three in the UK and US, and outsold Pink Floyd's previous album, The Final Cut (1983). It was supported by a successful world tour between 1987 and 1989, including a free performance on a barge floating on the Grand Canal in Venice, Italy.

Background

[edit]After the release of Pink Floyd's 1983 album The Final Cut, viewed by some as a de facto solo record by bassist and songwriter Roger Waters,[4][5] the band members worked on solo projects. Guitarist David Gilmour expressed feelings about his strained relationship with Waters on his second solo album, About Face (1984), and finished the accompanying tour as Waters began touring to promote his debut solo album, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking.[6] Although both had enlisted a range of successful performers, including in Waters' case Eric Clapton, their solo acts attracted fewer fans than Pink Floyd; poor ticket sales forced Gilmour to cancel several concerts, and critic David Fricke felt that Waters' show was "a petulant echo, a transparent attempt to prove that Roger Waters was Pink Floyd".[7] Waters returned to the US in March 1985 with a second tour, this time without the support of CBS Records, which had expressed its preference for a new Pink Floyd album; Waters criticised the corporation as "a machine".[8]

At that time, certainly, I just thought, I can't really see how we can make the next record or if we can it's a long time in the future, and it'll probably be more for, just because of feeling of some obligation that we ought to do it, rather than for any enthusiasm.

After drummer Nick Mason attended one of Waters' London performances in 1985, he found he missed touring under the Pink Floyd name. His visit coincided with the release in August of his second solo album, Profiles, on which Gilmour sang.[10][11] With a shared love of aviation, Mason and Gilmour were taking flying lessons and together bought a de Havilland Dove aeroplane. Gilmour was working on other collaborations, including a performance for Bryan Ferry at 1985's Live Aid concert, and co-produced the Dream Academy's self-titled debut album.[12]

In December 1985, Waters announced that he had left Pink Floyd, which he believed was "a spent force creatively".[13][14] After the failure of his About Face tour, Gilmour hoped to continue with the Pink Floyd name. The threat of a lawsuit from Gilmour, Mason and CBS Records was meant to compel Waters to write and produce another Pink Floyd album with his bandmates, who had barely participated in making The Final Cut; Gilmour was especially critical of the album, labelling it "cheap filler" and "meandering rubbish".[15]

They threatened me with the fact that we had a contract with CBS Records and that part of the contract could be construed to mean that we had a product commitment with CBS and if we didn't go on producing product, they could a) sue us and b) withhold royalties if we didn't make any more records. So they said, 'that's what the record company are going to do and the rest of the band are going to sue you for all their legal expenses and any loss of earnings because you're the one that's preventing the band from making any more records.' They forced me to resign from the band because, if I hadn't, the financial repercussions would have wiped me out completely.

According to Gilmour, "I told [Waters] before he left, 'If you go, man, we're carrying on. Make no bones about it, we would carry on', and Roger replied: 'You'll never fucking do it.'"[17] Waters had written to EMI and Columbia declaring his intention to leave the group and asking them to release him from his contractual obligations. He also dispensed with the services of Pink Floyd manager Steve O'Rourke and employed Peter Rudge to manage his affairs.[10] This left Gilmour and Mason, in their view, free to continue with the Pink Floyd name.[18] In 2013, Waters said he regretted the lawsuit and had not understood English jurisprudence.[19]

In Waters' absence, Gilmour had been recruiting musicians for a new project. Months previously, keyboardist Jon Carin had jammed with Gilmour at his Hook End studio, where he composed the chord progression that became "Learning to Fly", and so was invited onto the team.[20] Gilmour invited Bob Ezrin (co-producer of 1979's The Wall) to help consolidate their material;[21] Ezrin had turned down Waters' offer of a role on the development of his new solo album, Radio K.A.O.S., saying it was "far easier for Dave and I to do our version of a Floyd record".[22] Ezrin arrived in England in mid-1986 for what Gilmour later described as "mucking about with a lot of demos".[23]

At this stage, there was no commitment to a new Pink Floyd release, and Gilmour maintained that the material might become his third solo album. CBS representative Stephen Ralbovsky hoped for a new Pink Floyd album, but in a meeting in November 1986, told Gilmour and Ezrin that the music "doesn't sound a fucking thing like Pink Floyd".[24] By the end of that year, Gilmour had decided to make the material into a Pink Floyd project,[9] and agreed to rework the material that Ralbovsky had found objectionable.[24]

Recording

[edit]You can't go back ... You have to find a new way of working, of operating and getting on with it. We didn't make this remotely like we've made any other Floyd record. It was different systems, everything.

Gilmour experimented with songwriters such as Eric Stewart and Roger McGough, but settled on Anthony Moore,[26] who was credited as co-writer of "Learning to Fly" and "On the Turning Away". Whereas many prior Pink Floyd albums are concept albums, Gilmour chose a more conventional approach of a collection of songs without a thematic link.[27] Gilmour later said that the project had been difficult without Waters.[28]

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was recorded in several studios, mainly Gilmour's houseboat studio Astoria, moored on the Thames; according to Ezrin, "working there was just magical, so inspirational; kids sculling down the river, geese flying by...".[23] Andy Jackson was brought in to engineer. During sessions held between November 1986 and February 1987,[29] Gilmour's band worked on new material, which in a change from previous Pink Floyd albums was mostly recorded with a 32-track ProDigi digital recorder apart from the drum tracks, which were recorded with a 24-track analogue machine.[30] This trend of using new technologies continued with the use of MIDI synchronisation, aided by an Apple Macintosh computer.[24][31]

Ezrin suggested incorporating rap, an idea dismissed by Gilmour.[32] After agreeing to rework the material that Ralbovsky had found objectionable, Gilmour employed session musicians such as Carmine Appice and Jim Keltner. Both drummers replaced Mason on several songs; Mason was concerned that he was too out of practice to perform on the album, and instead busied himself with its sound effects.[24][33] Some drum parts were also performed by drum machines.[34] In his memoir, Mason wrote: "In hindsight, I really should have had the self-belief to play all the drum parts. And in the early days of life after Roger, I think David and I felt that we had to get it right, or we would be slaughtered."[35]

During the sessions, Gilmour was asked by the wife of Pink Floyd's former keyboardist, Richard Wright, if he could contribute. A founding member of the band, Wright had left in 1981, and there were legal obstacles to his return; after a meeting in Hampstead he was recruited as a paid musician on a weekly wage of $11,000.[36][37] Gilmour said in an interview that Wright's presence "would make us stronger legally and musically". However, his contributions were minimal; most of the keyboard parts had already been recorded, and so from February 1987 Wright played some background reinforcement on a Hammond organ, and a Rhodes piano, and added vocal harmonies. He also performed a solo in "On the Turning Away", which was discarded, according to Wright, "not because they didn't like it ... they just thought it didn't fit".[25]

Gilmour later said: "Both Nick and Rick were catatonic in terms of their playing ability at the beginning. Neither of them played on this at all really. In my view, they'd been destroyed by Roger." Gilmour's comments angered Mason, who said: "I'd deny that I was catatonic. I'd expect that from the opposition, it's less attractive from one's allies. At some point, he made some sort of apology." Mason conceded that Gilmour was nervous about how the album would be perceived.[36]

"Learning to Fly" was inspired by Gilmour's flying lessons, which occasionally conflicted with his studio duties.[38] The track also contains a recording of Mason's voice during takeoff.[39] The band experimented with samples, and Ezrin recorded the sound of Gilmour's boatman Langley Iddens rowing across the Thames.[23] Iddens' presence at the sessions became vital when Astoria began to lift in response to the rapidly rising river, which was pushing the boat against the pier on which it was moored.[33]

"The Dogs of War" is a song about "physical and political mercenaries", according to Gilmour. It came about through a mishap in the studio when a sampling machine began playing a sample of laughter, which Gilmour thought sounded like a dog's bark.[40] "Terminal Frost" was one of Gilmour's older demos, which he decided to leave as an instrumental.[41] Conversely, the lyrics for "Sorrow" were written before the music. The song's opening guitar solo was recorded in the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. A 24-track mobile studio piped Gilmour's guitar tracks through a public address system, and the resulting mix was then recorded in surround sound.[42]

Legal disputes

[edit]

The sessions were interrupted by the escalating disagreement between Waters and Pink Floyd over who had the rights to the Pink Floyd name. O'Rourke, believing that his contract with Waters had been terminated illegally, sued Waters for £25,000 of back-commission.[23] In a late-1986 board meeting of Pink Floyd Music Ltd (Pink Floyd's clearing house for all financial transactions since 1973), Waters learnt that a bank account had been opened to deal exclusively with all monies related to "the new Pink Floyd project".[43] He immediately applied to the High Court to prevent the Pink Floyd name from being used again,[10] but his lawyers discovered that the partnership had never been formally confirmed. Waters returned to the High Court in an attempt to gain a veto over further use of the band's name. Gilmour's team responded by issuing a press release affirming that Pink Floyd would continue to exist; however, Gilmour told a Sunday Times reporter: "Roger is a dog in the manger and I'm going to fight him, no one else has claimed Pink Floyd was entirely them. Anybody who does is extremely arrogant."[36][44]

Waters twice visited Astoria, and with his wife had a meeting in August 1986 with Ezrin, who later suggested that he was being "checked out". As Waters was still a shareholder and director of Pink Floyd Music, he was able to block any decisions made by his former bandmates. Recording moved to Mayfair Studios in February 1987, and from February to March – under the terms of an agreement with Ezrin to record close to his home – to A&M Studios in Los Angeles: "It was fantastic because ... the lawyers couldn't call in the middle of recording unless they were calling in the middle of the night."[29][45] The bitterness of the row between Waters and Pink Floyd was covered in a November 1987 issue of Rolling Stone, which became the magazine's best-selling issue of that year.[36] The legal disputes were resolved out of court by the end of 1987.[46][47]

Packaging and title

[edit]

Careful consideration was given to the album's title, with the initial three contenders being Signs of Life, Of Promises Broken and Delusions of Maturity. The final title appears as a line in the chorus of "One Slip".[48]

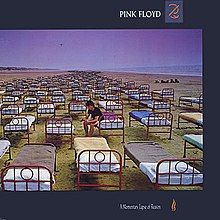

For the first time since 1977's Animals, designer Storm Thorgerson was employed to work on a Pink Floyd studio album cover.[nb 3] His finished design was a long river of hospital beds arranged on a beach, inspired by a phrase from "Yet Another Movie" and Gilmour's vague hint of a design that included a bed in a Mediterranean house, as well as "vestiges of relationships that have evaporated, leaving only echoes".[49] The cover shows hundreds of hospital beds assembled in July 1987 on Saunton Sands in North Devon,[50] where some of the scenes for Pink Floyd – The Wall were filmed.[51][52] The beds were arranged by Thorgerson's colleague Colin Elgie.[53] A hang glider in the sky references "Learning to Fly". The photographer, Robert Dowling, won a gold award at the Association of Photographers Awards for the image, which took about two weeks to create. Some versions of the cover do not feature the hang glider, and other versions feature a nurse making one of the beds.[54]

To emphasise that Waters had left the band, the inner gatefold featured a photograph of just Gilmour and Mason shot by David Bailey. Its inclusion marked the first time since Meddle (1971) that a group photo had been used in the artwork of a Pink Floyd album. Wright was represented only by name, on the credits.[55][56] According to Mason, Wright's leaving agreement contained a clause that prevented him rejoining the band, and "consequently we had to be careful about what constituted being a member".[57]

Release and reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | 2/5[61] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| The Village Voice | C[63] |

A Momentary Lapse of Reason was released in the UK and US on 7 September 1987.[nb 4] It went straight to number three in both countries, held from the top spot in the US by Michael Jackson's Bad and Whitesnake's self-titled album.[55] It spent 34 weeks on the UK Albums Chart.[64] It was certified silver and gold in the UK on 1 October 1987, and gold and platinum in the US on 9 November. It went double platinum on 18 January the following year, triple platinum on 10 March 1992, and quadruple platinum on 16 August 2001,[65] greatly outselling The Final Cut.[66]

Gilmour presented A Momentary Lapse as a return to an older Pink Floyd sound, citing his belief that under Waters' tenure, lyrics had become more important than music. He said that their albums The Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here were successful "not just because of Roger's contributions, but also because there was a better balance between the music and the lyrics [than on later albums]".[67] Waters said of A Momentary Lapse: "I think it's very facile, but a quite clever forgery ... The songs are poor in general; the lyrics I can't quite believe. Gilmour's lyrics are very third-rate."[68] Wright said Waters' criticisms were "fair".[55] In a later interview, Waters said the album had "a couple of really nice tunes" and chord sequences and melodies he would have retained had he been involved.[69]

In Q, Phil Sutcliffe wrote that it "does sound like a Pink Floyd album" and highlighted the two-part "A New Machine" as "a chillingly beautiful vocal exploration" and a "brilliant stroke of imagination". He concluded: "A Momentary Lapse is Gilmour's album to much the same degree that the previous four under Floyd's name were dominated by Waters … Clearly it wasn't only business sense and repressed ego but repressed talent which drove the guitarist to insist on continuing under the band brand-name."[70] Recognising the return to a more music-oriented approach, Sounds said the album was "back over the wall to where diamonds are crazy, moons have dark sides, and mothers have atom hearts".[71]

Conversely, Greg Quill of the Toronto Star wrote: "Something's missing here. This is, for all its lumbering weight, not a record that challenges and provokes as Pink Floyd should. A Momentary Lapse of Reason, sorry to say, is mundane, predictable."[72] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote: "You'd hardly know the group's conceptmaster was gone – except that they put out noticeably fewer ideas."[63] In 2016, AllMusic critic William Ruhlmann described it as a "Gilmour solo album in all but name".[58]

In 2016, Nick Shilton chose A Momentary Lapse of Reason as one of the "Top 10 Essential 80s Prog Albums" for Prog. He wrote: "While it's not a patch on the Floyd masterworks of the 70s, it merits inclusion here. The ironically titled 'Signs of Life' is an instrumental prelude for 'Learning to Fly' which showcases Gilmour's guitar, while the pulsating 'The Dogs of War' is considerably darker, and the uplifting 'On the Turning Away' simply sublime."[73]

Reissues

[edit]A Momentary Lapse of Reason was reissued in 1988 as a limited-edition vinyl with posters and a guaranteed ticket application for Pink Floyd's upcoming UK concerts.[nb 5] It was digitally remastered and rereleased in 1994.[nb 6] A tenth-anniversary edition was issued in the US in 1997.[nb 7]

In December 2019, A Momentary Lapse of Reason was reissued again as part of the Later Years box set. It was updated and remixed by Gilmour and Jackson, with restored contributions from Wright and newly recorded drum tracks from Mason to "restore the creative balance between the three Pink Floyd members".[75] Rolling Stone described this version as "more tasteful ... [It] doesn't drown in eighties reverb the way the original did ... Although none of the Momentary Lapse remixes will be dramatic enough to sway the band's critics, they add clarity to what Gilmour was trying to achieve."[76]

Tour

[edit]

Pink Floyd toured for A Momentary Lapse of Reason before it was complete. Early rehearsals were chaotic; Mason and Wright were out of practice, and, realising he had taken on too much work, Gilmour asked Ezrin to take charge. Gilmour and Mason funded the start-up costs; Mason, separated from his wife, used his Ferrari 250 GTO as collateral. Matters were complicated when Waters contacted several US promoters and threatened to sue if they used the Pink Floyd name. Some promoters were offended by Waters' threat, and several months later 60,000 tickets went on sale in Toronto, selling out within hours.[49][52]

As the new line-up (with Wright) toured throughout North America, Waters' Radio K.A.O.S. tour was sometimes close by. Waters forbade the members of Pink Floyd to attend his concerts,[nb 8] which were generally in smaller venues. Waters also issued a writ for copyright fees for use of the Pink Floyd flying pig; Pink Floyd responded by attaching a huge set of male genitalia to the balloon's underside to distinguish it from Waters' design. By November 1987, Waters had given up, and on 23 December a legal settlement was reached at a meeting on Astoria.[27]

The Momentary Lapse tour beat box office records in every US venue it booked, and was the most successful US tour that year. Tours of Australia, Japan, and Europe followed, before two more tours of the US. Almost every venue was sold out. A live album, Delicate Sound of Thunder, was released on 22 November 1988, followed in June 1989 by a concert video. A few days later, the live album was played in orbit, on board Soyuz TM-7. The tour eventually came to an end by closing the Silver Clef Award Winners Concert, at Knebworth Park on 30 June 1990, after 200 performances, a gross audience of 4.25 million fans, and box office receipts of more than £60 million (not including merchandising).[78] The tour included a free performance on a barge floating on the Grand Canal in Venice, Italy.[79]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written and co-written by David Gilmour; co-writers are listed alongside.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Signs of Life" | 4:24 | |

| 2. | "Learning to Fly" |

| 4:52 |

| 3. | "The Dogs of War" |

| 6:05 |

| 4. | "One Slip" | 5:10 | |

| 5. | "On the Turning Away" |

| 5:42 |

| 6. | "Yet Another Movie" | 6:14 | |

| 7. | "Round and Around" | 1:13 | |

| 8. | "A New Machine (Part 1)" | 1:46 | |

| 9. | "Terminal Frost" | 6:17 | |

| 10. | "A New Machine (Part 2)" | 0:38 | |

| 11. | "Sorrow" | 8:47 |

Note

- Since the 2011 remasters, and the Discovery box set, "Yet Another Movie" and "Round and Around" are indexed as individual tracks.

- Tracks 1–5 on side one and 6–11 on side two of vinyl releases

- The vinyl release of the 2019 mix however contain tracks 1-3 on side one, 4-5 on side two, 6-10 on side three, and track 11 on side four

Personnel

[edit]|

Pink Floyd[80]

Additional personnel

|

Technical personnel

|

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[113] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[114] | Platinum | 200,000[115] |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[116] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Brazil | — | 150,000[117] |

| Canada (Music Canada)[118] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| France (SNEP)[119] | Platinum | 300,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[120] | Gold | 250,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[121] sales since 2009 |

Gold | 25,000* |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[122] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[123] | Gold | 50,000[123] |

| Poland (ZPAV)[124] | Gold | 10,000‡ |

| Portugal (AFP)[125] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[126] | Platinum | 100,000^ |

| Sweden (GLF)[127] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[128] | 2× Platinum | 100,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[129] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[130] certified sales 1987-2001 |

4× Platinum | 4,000,000^ |

| United States Nielsen sales 1991-2008 |

— | 1,700,000[131] |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide | — | 10,000,000[132] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Two alternate covers were also released for streaming platforms and other reissues: one excludes the overlay and features a lady cleaning the land, while the other shows a close-up of the man sitting on a bed and excludes the title

- ^ Photographs of the band on stage were used on a poster that was included in copies of 1973's The Dark Side of the Moon.[48]

- ^ Thorgerson also worked on the cover of the 1981 compilation A Collection of Great Dance Songs.[48]

- ^ UK EMI EMD 1003 (vinyl album), EMI CDP 7480682 (CD album). US Columbia OC 40599 (vinyl album released 8 September 1987), Columbia CK 40599 (CD album)[56]

- ^ UK EMI EMDS 1003[74]

- ^ UK EMI CD EMD 1003[74]

- ^ US Columbia CK 68518[74]

- ^ Mason (2005) states that "rumour had it we would not be allowed in"[77]

Footnotes

- ^ "Music Week" (PDF). p. 35.

- ^ "UK promo disc with release date". Discogs. 1987.

- ^ Jon Pareles (15 September 2008). "Richard Wright, Member of Pink Floyd, Dies at 65". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Watkinson & Anderson 2001, p. 133

- ^ Mabbett 1995, p. 89

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 302–309

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 249–250

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 256–257

- ^ a b In the Studio with Redbeard, A Momentary Lapse of Reason (Radio broadcast), Barbarosa Ltd. Productions, 2007

- ^ a b c Blake 2008, pp. 311–313

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 257

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 258–260

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 262–263

- ^ Jones, Peter (22 November 1986), "It's the Final Cut: Pink Floyd to Split Officially", Billboard, p. 70, retrieved 22 September 2009

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 261–262

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 240

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 245

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 263

- ^ "Pink Floyd star Roger Waters regrets suing band". BBC News. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 316

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 315, 317

- ^ Schaffner 1991, pp. 267–268

- ^ a b c d Blake 2008, p. 318

- ^ a b c d Schaffner 1991, pp. 268–269

- ^ a b Schaffner 1991, p. 269

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 284–285

- ^ a b Povey 2007, p. 241

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 320

- ^ a b Povey 2007, p. 246

- ^ Pacuła, Wojciech (1 July 2020). "Technology: Mitsubishi ProDigi". High Fidelity. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Mason 2005, pp. 284–286

- ^ Michaels, Sean (21 March 2013). "Pink Floyd producer tried to make them go hip-hop". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b Mason 2005, p. 287

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 319

- ^ Chiu, David. "Pink Floyd's 'A Momentary Lapse of Reason' Gets An Update Three Decades Later". Forbes. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Manning 2006, p. 134

- ^ Blake 2008, pp. 316–317

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 267

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 229

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 204

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 272

- ^ MacDonald 1997, p. 268

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 270

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 271

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 321

- ^ Danton, Eric R. (19 September 2013). "Roger Waters Regrets Pink Floyd Legal Battle". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Roger Waters: 'I was wrong to sue Pink Floyd'". BBC News. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd - The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ a b Blake 2008, p. 322

- ^ Pink Floyd's Facebook post on 7 September 2020 titled "Here's a look at the creation of the cover of the #PinkFloyd album A Momentary Lapse of Reason, with footage taken from The Later Years boxset" featuring the video excerpt "Cover shoot for Pink Floyd's A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (1:00)

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 290

- ^ a b Povey 2007, p. 243

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 273

- ^ Blake 2008, p. 323

- ^ a b c Blake 2008, pp. 326–327

- ^ a b Povey 2007, p. 349

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 397

- ^ a b Ruhlmann, William. "Pink Floyd A Momentary Lapse of Reason". AllMusic. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (20 May 2014). "Pink Floyd's 14 studio albums rated". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9780857125958.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, p. 874

- ^ "Pink Floyd: Album Guide". rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (29 December 1987). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ David Roberts, ed. (2006). British Hit Singles and Albums. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 427. ISBN 978-1904994107.

- ^ Povey 2007, pp. 349–350

- ^ Povey 2007, p. 230

- ^ Schaffner 1991, p. 274

- ^ Fricke, David (19 November 1987). "Pink Floyd: The Inside Story". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 144

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil (October 1987), "Pink Floyd: A Momentary Lapse of Reason", Q; available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required)

- ^ Manning 2006, p. 136

- ^ Quill, Greg (11 September 1987), "Has Pink Floyd changed its color to puce?" (Registration required), Toronto Star, retrieved 24 January 2010 – via infoweb.newsbank.com

- ^ Shilton, Nick (7 August 2016). "The Top 10 Essential 80s Prog Albums". Louder. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Povey 2007, p. 350

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (29 August 2019). "Pink Floyd Ready Massive 'The Later Years' Box Set". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ Grow, Kory (12 December 2019). "'The Later Years 1987–2019' Chronicles Pink Floyd After it Became David Gilmour's Show". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ Mason 2005, p. 300

- ^ Povey 2007, pp. 243–244, 256–257

- ^ Blacklast, Johnny (30 March 2022). "The true story of the day Pink Floyd tried to sink Venice". Loudersound. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2017). Pink Floyd All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track (1st ed.). Edinburgh: Black Dog & Leventhal. pp. 500–517. ISBN 978-0316439244.

- ^ A Momentary Lapse Of Reason (Booklet). Pink Floyd. EMI (50999 028959 2 5). 2011.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ "Australiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (Illustrated ed.). St. Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 233. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Top RPM Albums: Issue 0886". RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd: A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2021. 44. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "IRMA – Irish Charts". Irish Recorded Music Association. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ "Classifiche". Musica e Dischi (in Italian). Retrieved 30 May 2022. Set "Tipo" on "Album". Then, in the "Titolo" field, search "A momentary lapse of reason".

- ^ "Charts.nz – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Pink Floyd Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1987". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "European Top 100 Albums – 1987" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 4, no. 51/52. 26 December 1987. p. 35. OCLC 29800226. Retrieved 30 November 2021 – via World Radio History. Digit page 37 on the PDF archive.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Top Selling Albums of 1987 — The Official New Zealand Music Chart". Recorded Music New Zealand. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ "Schweizer Jahreshitparade 1987". hitparade.ch. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Album 1988". dutchcharts.nl. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Top 100 Album-Jahrescharts" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 1988". Billboard. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "Összesített album- és válogatáslemez-lista - eladási darabszám alapján - 2021" (in Hungarian). Mahasz. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Aria Album Charts – 1988". Aria Charts. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Glenn A. Baker (28 January 1989). "Australia '89" (PDF). Billboard. Vol. 101, no. 4. p. A-4. Retrieved 22 June 2021 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Floyd & Mac na arena". Jornal do Brasil. 6 October 1988. p. 7. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Music Canada. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "French album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Moementary Lapse of Reason" (in French). InfoDisc. Select PINK FLOYD and click OK.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Pink Floyd; 'A Momentary Lapse of Reason')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 28 October 2020. Select "2016" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "A Momentary Lapse of Reason" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Retrieved 13 September 2018. Enter A Momentary Lapse of Reason in the "Artiest of titel" box. Select 1988 in the drop-down menu saying "Alle jaargangen".

- ^ a b "Gold & Platinum Awards 1987" (PDF). Music & Media. 26 December 1987. p. 44. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Złote płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2022 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. 11 May 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum Awards 1987" (PDF). Music & Media. 26 December 1987. p. 44. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (PDF) (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. p. 922. ISBN 84-8048-639-2. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 1987−1998" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('A Momentary Lapse of Reason')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "British album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ "American album certifications – Pink Floyd – A Momentary Lapse of Reason". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ^ Barnes, Ken (16 February 2007). "Sales questions: Pink Floyd". USA Today. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ^ Wyman, Bill (3 August 2017). "All 165 Pink Floyd Songs, Ranked From Worst to Best". Vulture. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

Bibliography

- Blake, Mark (2008), Comfortably Numb – The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (paperback ed.), Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-0-306-81752-6

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999), MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide, Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press, ISBN 1-57859-061-2

- Mabbett, Andy (1995), The Complete Guide to the Music of Pink Floyd, Omnibus Press, ISBN 0-7119-4301-X

- MacDonald, Bruno (1997), Pink Floyd: Through the Eyes of the Band, Its Fans, Friends and Foes (paperback ed.), Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80780-7

- Manning, Toby (2006), The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st ed.), London: Rough Guides, ISBN 1-84353-575-0

- Mason, Nick (2005), Philip Dodd (ed.), Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd (paperback ed.), London: Phoenix, ISBN 0-7538-1906-6

- Povey, Glenn (2007), Echoes, Bovingdon: Mind Head Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1991), Saucerful of Secrets (1st ed.), London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 0-283-06127-8

- Watkinson, Mike; Anderson, Pete (2001), Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett & the Dawn of Pink Floyd (illustrated ed.), Omnibus Press, ISBN 0-7119-8835-8

External links

[edit]- A Momentary Lapse of Reason at Discogs (list of releases)