Aga Khan Award for Architecture

| Aga Khan Award for Architecture | |

|---|---|

Logo for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture | |

| Awarded for | Architectural concepts that successfully address the needs and aspirations of Muslim societies in the fields of contemporary design, social housing, community development and improvement, restoration, reuse and area conservation, as well as landscape design and improvement of the environment. |

| Sponsored by | Aga Khan IV |

| Reward(s) | US$1-million |

| First awarded | 1978 |

| Last awarded | 2022 |

| Website | the.akdn/award-for-architecture |

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA) is an architectural prize established by Aga Khan IV in 1977. It aims to identify and reward architectural concepts that successfully address the needs and aspirations of Muslim societies in the fields of contemporary design, social housing, community development and improvement, restoration, reuse and area conservation, as well as landscape design and improvement of the environment.[1]

The award is associated with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN).

Prize

[edit]The Aga Khan Award for Architecture is presented in three-year cycles and has a monetary prize totalling US$1 million that is shared by multiple winning projects.[2] It recognizes projects, teams, and stakeholders in addition to buildings and people.[3]

Chairman's Award

[edit]The Chairman's Award is given in honour of accomplishments that fall outside the mandate of the Master Jury.[4] It recognises lifetime achievements of individuals and has been presented four times: in 1980 to Egyptian architect and urban planner Hassan Fathy,[5] in 1986 to Iraqi architect and educator Rifat Chadirji,[6] in 2001 to Sri Lankan architect Geoffrey Bawa,[7] and in 2010 to historian of Islamic art and architecture Oleg Grabar.[8]

History

[edit]Prince Karim Aga Khan IV established the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1977.[9] At the time, very few architectural prizes of international scope existed.[10] It has been noted that the award emerged from "the Aga Khan's sadness at the state of architecture in the Islamic world of the 1970s",[11] and his conviction of the importance that the built environment holds in shaping a society's quality of life.[12]

Twenty years earlier, upon inheriting the seat of Imamat of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, the Aga Khan had become responsible for the wellbeing of the Ismaili community, which mostly live in the developing countries of Asia, Africa and the Middle East.[13] He was concerned at the absence of design thinking that could respond to specific challenges in those parts of the world.[13]

A relentless push for development had led to cheap copies of foreign architectural designs that held no connection or respect for the places where they were being built.[14] The Aga Khan also worried about the rapid disappearance of centuries of distinctive architectural tradition that embodied a continuity of Islamic values,[11][14] resulting in an absence of "architecture that could speak to and about the Muslim world".[15]

These problems were most acutely felt during the planning of the Aga Khan University and teaching hospital in Karachi.[15] Questions raised in this process – including the need for a contemporary visual language for the Islamic built environment, as well as for architects trained in modern technologies and sensitive to the diversity, values and dignity of Muslim culture – would inform the creation of the Award.[14]

Reviving creativity

[edit]By the 1970s, the decline of the built environment of Muslim societies and loss of cultural identity had become apparent to others as well.[14][16] From the outset the Aga Khan recruited a number of people to help define the award.[15] Among the first were Oleg Grabar a professor at the Harvard Department of Fine Arts,[17] William Porter then Dean of the MIT School of Architecture and Planning,[18] architectural historian Renata Holod, and Pakistani architect Hasan Udhin Khan.[15] They were joined by others, including Nader Ardalan, Hugh Casson, Charles Correa, and Hassan Fathy.[15]

Members of the team travelled widely – from Morocco to Indonesia.[15] They debated the cultural role of architecture, the parameters of the award and how to structure its processes.[15] The award was shaped by consultations held with chambers of architects and ministries of urbanism and culture. The first Aga Khan Award for Architecture Seminar was held during April 1978 in Aiglemont, Gouvieux, France.[19] Subsequent seminars have been held in Istanbul, Jakarta, Fez, Amman, Beijing, Dakar, Sana'a, Cairo, Granada and elsewhere.[20]

In seeking to define what "Islamic architecture" meant,[14][15] it became apparent that no singular definition was to be found.[14] Instead, the seminars brought to light the diversity of what constituted Islamic architecture.[19] This was recognized as a strength and a dormant source of creativity that the Award would seek to revive.[14]

Knowledge from architecture

[edit]Unlike conventional prizes that applaud the accomplishments of individual architects, the Aga Khan Award selects projects that improve the quality of life and recognizes all those who have a role in realizing them.[16] This includes clients, builders, artisans and decision makers.[21] Architecture is viewed as a collaborative endeavour in which architects play a role.[12]

In the four decades since its establishment, the Award has documented more than 9,000 projects[21] and actively contributed to the architectural discourse.[22][12][16] It has promoted the view that architecture is deeply connected with society and can respond to issues that are of local, national and even international relevance.[16]

The Award has brought together practitioners from different geographies and fields like philosophy, social sciences, and the arts,[16] who have served as jurors, steering committee members, technical reviewers, or attended seminars.[16]

Award process

[edit]The Aga Khan Award runs in three-year cycles and is governed by a steering committee chaired by the Aga Khan.[23] A new committee is constituted each cycle to establish the eligibility criteria for projects, provide thematic direction with reference to current concerns, and to develop plans for the long-term future of the award. The committee is also responsible for seminars and field visits, the award ceremony, publications and exhibitions. At the commencement of each cycle, the steering committee is convened to select a master jury[15] that is diverse in its perspectives and has in past cycles included sociologists, philosophers, artists as well as architects.[24]

In each cycle, submissions are received from a global network of approximately 500 nominators – women and men who live in Muslim societies and whose identities are kept anonymous throughout the award process.[16] Independent nominations are also accepted in accordance with the award's published guidelines and procedures.[16] Several hundred submissions are typically received in each cycle,[16] and the master jury narrows the field to a short-list.[24]

Professional, technical reviewers visit the short-listed projects to understand the living impact of each one on people and the surrounding area. They prepare exhaustive documentation, providing fact-based analysis for the master jury's consideration.[24]

Over the decades, many notable figures have served on the award's steering committees and master juries, including Homi K. Bhabha, Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Glenn Lowry, Fumihiko Maki, Jacques Herzog, Ricardo Legoretta and Farshid Moussavi.[15][25] The award is administered from Geneva as part of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and Farrokh Derakhshani has served as Director of the Award since 1982.[26]

Promotion

[edit]The Aga Khan Foundation funded the television series Architects on the Frontline which was about entries to the competition. The media watchdog Ofcom criticised BBC World News for breaking United Kingdom broadcasting rules with the series, which praised the competition; viewers were not informed that it was sponsored content.[27]

Award cycles

[edit]Prizes totalling up to US$1m[1] are presented every three years to projects selected by the Master Jury.[23] Since 1977, documentation has been compiled on over 7500 building projects located throughout the world, of which over 100 projects have received awards.[28]

First (1978–1980)

[edit]The 1980 award ceremony took place at the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan. During this cycle, the Chairman's Award was given to Hassan Fathy in recognition of his lifelong commitment to architecture in the Muslim world. Prominent architect Muzharul Islam was a member of the Master Jury of the first Aga Khan Award for Architecture.

Award recipients:[29]

- Kampung Improvement Programme, Jakarta, Indonesia[30]

- Pondok Pesantren Pabelan, Central Java, Indonesia

- Ertegün House, Bodrum, Turkey

- Library and conference center of the Turkish Historical Society, Ankara, Turkey

- Mughal Sheraton Hotel, Agra, India

- Conservation of Sidi Bou Saïd, Tunis, Tunisia

- Restoration of the Rüstem Pasa Caravanserai, Edirne, Turkey

- National Museum, Doha, Qatar

- Ali Qapu, Chehel Sutun, and Hasht Behesht Restoration, Isfahan, Iran

- Halawa House, Agamy, Egypt, by Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil

- Medical Centre, Mopti, Mali

- Courtyard Houses, Agadir, Morocco

- Water Towers, Kuwait City, Kuwait

- Intercontinental Hotel and Conference Centre, Mecca, Saudi Arabia, by Rolf Gutbrod and Frei Otto

- Agricultural Training Centre, Nianing, Senegal

-

Conservation of Sidi Bou Saïd, Tunis

-

Mughal Sheraton Hotel, Agra

Second (1981–1983)

[edit]The 1983 award ceremony took place at the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. Award recipients:[31]

- Great Mosque of Niono, Mali

- Šerefudin's White Mosque, Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Ramses Wissa Wassef Arts Centre, Giza, Egypt

- Nail Çakirhan Residence, Akyaka Village, Muğla, Turkey

- Hafsia Quarter I, Tunis, Tunisia

- Tanjong Jara Beach Hotel and Rantau Abang Visitors' Centre, Kuala Terengganu, Malaysia

- Résidence Andalous, Sousse, Tunisia

- Hajj Terminal, King Abdulaziz International Airport, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, by Fazlur Khan

- Tomb of Shah Rukn-i-'Alam, Multan, Pakistan

- Darb Qirmiz Quarter, Cairo, Egypt

- Restoration of Azem Palace, Damascus, Syria

-

Nail Çakirhan Residence, Akyaka Village, Turkey

-

Azem Palace, Damascus, Syria

-

Hajj Terminal, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

-

Mausoleum of Shah Rukn-i-Alam in Multan, Pakistan

Third (1984–1986)

[edit]The 1986 award ceremony took place at El Badi Palace in Marrakesh, Morocco. The brief prepared by the Steering Committee for this award cycle focused on the preservation and continuation of cultural heritage, community building and social housing, and excellence in contemporary architectural expression.

Six winners were chosen from among 213 entries.[32] The conservation of Mostar Old Town and restoration of Al-Aqsa Mosque were examples of cultural heritage, the first theme, while the Yama Mosque and Bhong Mosque were noted for their innovation in translating traditional techniques and materials to meet contemporary requirements. The Social Security Complex and Dar Lamane Housing address the issues of community and social housing while remaining sensitive to local culture. The Chairman's Award for Lifetime Achievements was given to Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji.

Award recipients:[33]

- Social Security Complex, Istanbul, Turkey

- Dar Lamane Housing, Casablanca, Morocco

- Conservation of Mostar Old Town, Bosnia and Herzegovina[34]

- Restoration of Al-Aqsa Mosque, Noble Sanctuary, Jerusalem

- Yaama Mosque, Yaama, Tahoua, Niger

- Bhong Mosque, Bhong, Rahim Yar Khan District, Pakistan

-

Mostar Old Town

-

Restoration of Al-Aqsa Mosque, Jerusalem

-

Bhong Mosque, Punjab, Pakistan

Fourth (1987–1989)

[edit]The 1989 award ceremony took place at the Citadel of Salah Ed-Din in Cairo. The fourth cycle of the award considered 241 project nominations. Of these, 32 were short-listed for technical review[35] and the Master Jury selected 11 winners. Two themes were noted as areas of focus in this cycle: Revival of past vernacular traditions, and projects that reflect the efforts of individual patrons and of non-governmental organisations in improving society.

Projects such as the Great Omari Mosque and the Rehabilitation of Asilah seek to reconstruct and preserve heritage buildings for continued use, demonstrating the significance of these spaces within their communities. Meanwhile, the Grameen Bank Housing Programme and Sidi el-Aloui Primary School apply architectural solutions to address current socioeconomic issues.

Award recipients:[36]

- Great Omari Mosque (Sidon, Lebanon)

- Rehabilitation of Asilah (Asilah, Morocco)

- Grameen Bank Housing Programme (various locations in Bangladesh)

- Citra Niaga Urban Development (Samarinda, East Kalimantan, Indonesia)

- Gürel Family Summer Residence (Çanakkale, Turkey)

- Hayy Assafarat Landscaping and al-Kindi Plaza (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

- Sidi el-Aloui Primary School (Tunis, Tunisia)

- Corniche Mosque (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia), by Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

- National Assembly Building (Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka, Bangladesh), by Louis Kahn

- Institut du Monde Arabe (Paris, France), by Jean Nouvel and Architecture-Studio

-

Asilah Waterfront

-

National Assembly of Bangladesh, Dhaka

-

National Assembly Building, Dhaka

Fifth (1990–1992)

[edit]The 1992 award ceremony took place at the Registan Square in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Uzbek government also released a postal stamp to commemorate the award ceremony & restoration of Registan Square in Partnership with Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

Award recipients:[37]

- Kairouan Conservation Programme (Kairouan, Tunisia)

- Palace Parks Programme (Istanbul, Turkey)

- Cultural Park for Children (Cairo, Egypt)

- East Wahdat Upgrading Programme (Amman, Jordan)

- Kampung Kali Code (Yogyakarta, Indonesia)

- Stone Building System (Daraa Governorate, Syria)

- Demir Holiday Village (Bodrum, Turkey)

- Pan African Institute for Development (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso), by Association pour le Développement d'une Architecture et d'un Urbanisme Africains (A.D.A.U.A. – Association for the Development of African Architecture and Urban Planning)

- Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India (Ahmedabad, India), by Bimal Hasmukh Patel

-

Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India

-

Kairouan

Sixth (1993–1995)

[edit]The 1995 award ceremony took place at the Kraton Surakarta in Surakarta, Indonesia.

Award recipients:[38]

- Restoration of Bukhara Old City, Uzbekistan

- Conservation of Old San'a', Yemen

- Hafsia Quarter II, Tunis, Tunisia

- Khuda-ki-Basti Incremental Development Scheme, Hyderabad, Pakistan

- Aranya Community Housing [1], Indore, India, by B.V. Doshi[39]

- Great Mosque and Redevelopment of the Old City Centre Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Menara Mesiniaga, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Kaédi Regional Hospital, Kaedi, Mauritania, by ADAUA.

- Mosque of the Grand National Assembly, Ankara, Turkey

- Alliance Franco-Sénégalaise, Kaolack, Senegal

- Re-Forestation Programme of the Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey

- Landscaping Integration of the Soekarno-Hatta Airport, Cengkareng, Indonesia

-

Kaédi Regional Hospital

-

Bukhara Old City

-

San'a'

-

Menara Mesiniaga

Seventh (1996–1998)

[edit]The 1998 award ceremony took place at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. The Master Jury selected seven winning projects of the 424 presented. During this cycle, special emphasis was placed on projects that responded creatively to the emerging forces of globalization. Issues such as demographic pressure, environmental degradation, and the crisis of the nation-state, and the changes in lifestyle, cultural values, and relationships among social groups and between governments and people at large they prompted, were considered.

Of the winning projects, the rehabilitation of the Old City of Hebron and Slum Networking of Indore City sought to reclaim community space in environments strained by social, physical and environmental degradation. The Lepers Hospital created a sustainable and dignified shelter for a marginalized segment of society. The remaining projects were recognized for their contribution in evolving an architectural vocabulary in response to contemporary social and environmental challenges.[40]

Award recipients:[41]

- Rehabilitation of the Old City of Hebron

- Slum Networking of Indore, India by Himanshu Parikh

- Lepers Hospital, Chopda Taluka, Lasur, India by Per Christian Brynildsen and Jan Olav Jensen

- Salinger Residence, Bangi, Selangor, Malaysia

- Tuwaiq Palace, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Alhamra Arts Council, Lahore, Pakistan, by Nayyar Ali Dada

- Vidhan Bhavan, Bhopal, India[42] by Charles Correa

-

Alhamra Arts Council, Lahore

-

Hebron

Eighth (1999–2001)

[edit]The 2001 Award Presentation Ceremony took place at the Citadel of Aleppo in Syria. During this cycle, the Chairman's Award was given to Geoffrey Bawa to honour and celebrate his lifetime achievements in and contribution to the field of architecture.

Award recipients:[43]

- New Life for Old Structures (various locations, Iran)

- Aït Iktel (Abadou, Morocco)

- Kahere Eila Poultry Farming School (Koliagbe, Guinea)

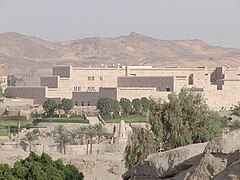

- Nubian Museum (Aswan, Egypt)

- SOS Children's Village (Aqaba, Jordan), by Ja'afar Tuqan

- Olbia Social Centre of Akdeniz University (Antalya, Turkey), by Cengiz Bektaş

- Bagh-e-Ferdowsi (Tehran, Iran)

- Datai Hotel (Langkawi, Malaysia)

-

Nubian Museum, Aswan

-

Nubian Museum, Aswan

Ninth (2002–2004)

[edit]The 2004 award ceremony took place at the Humayun's Tomb in New Delhi, India. During the ninth cycle, 378 projects were nominated. Of these, 23 were site-reviewed, and the Master Jury selected seven award recipients.[44] Notable among the recipients are the Sandbag Shelter Prototypes, developed by Nader Khalili to enable victims of natural disasters and war to build their own shelter using earth-filled sandbags and barbed wire. The resulting structures – made up of arches, domes and vaulted spaces built using superadobe techniques – provide earthquake resistance, shelter from hurricanes and flood resistance, while being aesthetically pleasing.[45]

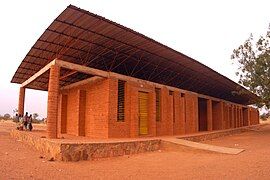

Other winning projects include a primary school in Gando, Burkina Faso, that combines high-caliber architectural design with local materials, techniques and community participation. The Bibliotheca Alexandria in Egypt and the Petronas Towers in Malaysia are examples of high-profile landmark buildings.

Award recipients:[46]

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt, by Norwegian architectural office Snøhetta

- Primary School, Gando, Burkina Faso, by Diébédo Francis Kéré

- Sandbag Shelter Prototypes (various locations), developed by Nader Khalili

- Restoration of Al-Abbas Mosque (Asnaf, Yemen)

- Old City of Jerusalem Revitalisation Programme, Jerusalem

- B2 House, Ayvacik, Turkey, by Han Tümertekin

- Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, by César Pelli

-

Petronas Towers, Kuala Lumpur

-

Bibliotheca Alexandrina

-

Primary School in Gando

-

Old city of Jerusalem

-

Petronas Towers within Kuala Lumpur cityscape

Tenth (2005–2007)

[edit]The 2007 Award Presentation Ceremony was held at the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. This cycle marked the 30th anniversary of the award. A total of 343 projects were presented for consideration, and 27 were reviewed on site by international experts.[48]

The award recipients were:[49]

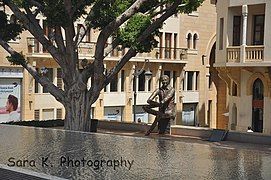

- Samir Kassir Square, Beirut, Lebanon

- Rehabilitation of the City of Shibam, Yemen

- Central Market, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

- University of Technology Petronas, Bandar Seri Iskandar, Malaysia, by Foster + Partners

- Restoration of the Amiriya Madrasa, Rada, Yemen

- Moulmein Rise Residential Tower, Singapore, by WOHA Architects

- Royal Netherlands Embassy, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, by Dick Van Gameren, Bjarne Mastenbroek

- Rehabilitation of the Walled City, Nicosia, Cyprus

- METI School in Rudrapur, Dinajpur, Bangladesh, by Anna Heringer

-

Samir Kassir Square, Beirut

-

Shibam

-

University of Technology Petronas

-

Amiriya Madrasa

-

Royal Netherlands Embassy, Addis Ababa

-

Büyük Han, Nicosia

Eleventh (2008–2010)

[edit]The 2010 Award Presentation Ceremony was held at the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar. A total of 401 projects were nominated of which 19 were shortlisted.[50]

The Chairman's Award went to Oleg Grabar.[8]

The award recipients were:[51]

- Wadi Hanifa Wetlands Project, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- Revitalisation of nineteenth and early twentieth-century architectural heritage of Tunis, Tunisia

- Research Centre and Museum, Madinat Al-Zahra, Cordoba, Spain, by Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos[52]

- Ipekyol Textile Factory, Edirne, Turkey

- Bridge School, Xiashi, Fujian, China

-

Wadi Hanifa

-

Al Elb Dam, Wadi Hanifa

-

Cathedral of St. Vincent de Paul, Tunis, 1897

-

Municipal Theatre, Tunis, by Jean Emile Resplandy, 1902

-

Madinat Al-Zahra, Spain

-

Madinat Al-Zahra, Spain

Twelfth (2011–2013)

[edit]The 2013 Award ceremony was held at the Castle of São Jorge in Lisbon, Portugal in September 2013.[28][53]

The winning projects are:[54][55]

- Emergency[56] Salam Centre for Cardiac Surgery,[57] Khartoum, Sudan, by Italian practice Studio Tamassociati, completed in 2010

- Revitalisation of Birzeit Historic Centre, Birzeit, Palestine

- Hassan II Bridge (Rabat-Salé Infrastructure Project, Rabat and Salé, Morocco

- Rehabilitation of Tabriz Bazaar, Tabriz, Iran

- Islamic Cemetery, Altach, Austria, by Austrian architect Bernardo Bader, inaugurated in 2012

-

Tabriz Bazaar

-

Islamic Cemetery, Altach

Thirteenth (2014–2016)

[edit]The 2016 Award ceremony for the six winners was held in Al-Ain, UAE on 6 November 2016:[58]

- Bait Ur Rouf Mosque in Uttara, Dhaka, Bangladesh by Marina Tabassum

- Friendship Centre in Gaibandha, Bangladesh by Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury / URBANA

- Hutong Children's Library and Art Centre in Beijing China, by ZAO/standardarchitecture and Zhang Ke

- Superkilen in Copenhagen, Denmark by Bjarke Ingels Group, Topotek 1, and Superflex

- Tabiat Pedestrian Bridge in Tehran, Iran by Diba Tensile Architecture / Leila Araghian and Alireza Behzadi

- Issam Fares Institute in Beirut, Lebanon by Zaha Hadid Architects

-

Superkilen, Copenhagen

-

Friendship Centre

-

Baitur Rauf Jame Mosque

-

Tabiat Bridge, Tehran

Fourteenth (2017–2019)

[edit]The Award ceremony for the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture was held on 13 September 2019 in Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan, Russia[59][60]

- Revitalization of Muharraq in Muharraq, Bahrain

- Arcadia Education Project in South Kanarchor, Bangladesh

- The Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, West Bank

- Public Spaces Development Programme in Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan, Russia

- Alioune Diop University Teaching and Research Unit in Bambey, Senegal, by IDOM

- Wasit Wetland Centre in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

-

Arcadia Education Centre, South Kanarchor, Bangladesh

-

Wasit Wetland Centre, Sharjah, UAE

Fifteenth (2020–2022)

[edit]The Award ceremony for the 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture was held on 31 October 2022 in Muscat, Oman:[61][62]

- Urban River Spaces in Jhenaidah, Bangladesh[63]

- Community Spaces in Rohingya Refugee Response in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh[64]

- Banyuwangi International Airport, Blimbingsari in East Java, Indonesia[65]

- Argo Contemporary Art Museum and Cultural Centre in Tehran, Iran[66]

- Renovation of Niemeyer Guest House in Tripoli, Lebanon[67]

- Kamanar Secondary School in Thionck Essyl, Senegal[68]

See also

[edit]- Aga Khan Historic Cities Support Programme, another architectural initiative of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture.

- Islamic architecture

- List of architecture prizes

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Aga Khan Award for Architecture Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine." ArchitectureWeek 9 January 2002.

- ^ "Aga Khan Award for Architecture Prize doubled to US$1 million". Canadian Architect. 26 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Alshehabi, Ghazi. "Bahrain News: Muharraq project shortlisted for $1 million architecture award". www.gdnonline.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Welch, Adrian (15 January 2010). "Aga Khan Award for Architecture: Architects". e-architect. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Lifetime Achievements of Hassan Fathy Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lifetime Achievements of Rifat Chadirji Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lifetime Achievements of Geoffrey Bawa Archived 19 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Speech by Oleg Grabar, Recipient of the 2010 Chairman's Award – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- ^ Blair, Sheila S.; Bloom, Jonathan M. (2 July 2009). Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t2082051.

- ^ YILMAZ KARAMAN, Özgül (2016). "Acoustic Comfort in Lecture Halls: The Dokuz Eylül University Faculty of Architecture". MEGARON / Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture e-Journal. doi:10.5505/megaron.2015.58076. ISSN 1309-6915.

- ^ a b "Saudi Aramco World : Shaking Up Architecture". archive.aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ a b c RWU Architecture Fall Lecture Series Farrokh Derakshani Sept. 13, 2017, archived from the original on 24 April 2020, retrieved 29 August 2019

- ^ a b Jodidio, Philip. (2007). Under the eaves of architecture : the Aga Khan : builder and patron. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 9783791337814. OCLC 166214221.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aga Khan IV (25 September 1979). Asia Society, Islamic architecture: a revival (Speech). Built environment of Islam today. New York, USA. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jodidio, Philip (2007). Under the Eaves of Architecture The Aga Khan: Builder and Patron. Prestel; First edition (25 Aug 2007). ISBN 978-3791337814.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Saudi Aramco World : Shaking Up Architecture". archive.aramcoworld.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ Graham; Lentz; Roxburgh; Necipoğlu. "Oleg Grabar Memorial Minutes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Former Dean Bill Porter Retires | MIT School of Architecture + Planning". sap.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Opening Remarks". Archnet. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Collections | Publication Series | Architectural Transformations in the Islamic World". Archnet. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ a b "The Revitalization of Muharraq in Bahrain is among the projects shortlisted for the Aga Khan Award for Architecture this year". Alayam.com (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Architectural diplomacy". www.architecturalrecord.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Aga Khan Award for Architecture announces Master Jury for 2007 – Canadian Architect". 12 January 2007. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "Aga Khan Award Winners for 2007 Named". www.architecturalrecord.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Steering Committee for Aga Khan Award's twelfth cycle announced | Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Steering Committee for Aga Khan Award's twelfth cycle announced | Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ^ "News channels breached sponsorship rules, Ofcom says". BBC News. 18 August 2015. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Twenty projects shortlisted for $1-million Aga Khan Award for Architecture – Canadian Architect". 11 May 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "1980 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Kampung Improvement Programme | Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "1983 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "The Changing Present, Loughran, G., Saudi Aramco World, Nov/Dec 1987: 28–37". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- ^ "1986 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ (AKTC) Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (ArchNet) Archived 8 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Better by Design, Loughran, G., Saudi Aramco World, Nov/Dec 1989: 28–33". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- ^ "1989 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "1992 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "1995 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Aranya Community Housing – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ Cynthia C. Davidson, ed. (1999). Legacies for the Future: Contemporary Architecture in Islamic Societies. New York: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-28087-8.

- ^ "1998 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Vidhan Bhavan, (ArchNet) Archived 8 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "2001 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 17 June 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2004 – Architecture & Urbanism magazine, No. 78/79, Autumn/Winter 2005, Tehran". Archived from the original on 2 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- ^ "Sandbag Shelters – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ^ 2004 Cycle Awards Recipients Archived 21 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See more construction images Archived 21 August 2023 at the Wayback Machine in Wikimedia Commons

- ^ "Nine Projects Receive 2007 Aga Khan Award for Archicture" (Press release). Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). 4 September 2007. Archived from the original on 10 September 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- ^ "2007 Cycle -– Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Jenna M. McKnight: Revealed: Winners of 2010 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, in the Architectural Record, 24 November 2010 Archived 7 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 1 December 2010

- ^ "2010 Cycle – Aga Khan Development Network". www.akdn.org. Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ "Article on the project by the architects, Enrique Sobejano and Fuensanta Nieto". Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ World Architecture News Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 6 May 2013

- ^ Cathleen McGuigan: "Aga Khan Awards Go to Projects that Build Community" Archived 2 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, in The Architectural Record, 6 September 2013

- ^ Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2013 Cycle Award Recipients Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ www.ideafutura.com, Idea Futura srl -. "Emergency – Sito Ufficiale – Home". www.emergency.it. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ "The Salam Centre for Cardiac Surgery – Home page". www.salamcentre.emergency.it. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ Anna Fixsen: "BIG, Zaha Hadid Architects Among 2016 Aga Khan Award Recipients" Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Architectural Record, 3 October 2016

- ^ Christele Harrouk (29 August 2019). "The 2019 Winners of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture". ArchDaily. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "AKAA 2019 Award Presentation Ceremony". Aga Khan Development Network. Archived from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ "Winners of the 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture announced". Canadian Architect. 22 September 2022. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "The six winning projects of 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture embody an inclusive, pluralistic outlook". Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 2 November 2022. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "2 Bangladesh projects win Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2022". Dhaka Tribune. 22 September 2022. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture: 2 Bangladeshi projects among winners". The Daily Star. UNB. 22 September 2022. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Winners announced for Aga Khan Award for Architecture 2022". World Architecture Community. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Oscar Holland (23 September 2022). "Aga Khan Award: $1 million prize recognizes world's best new community architecture". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Gillett, Katy (22 September 2022). "Lebanese guesthouse among winners of 2022 Aga Khan Award for Architecture". The National. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Newsource, C. N. N. (23 September 2022). "Aga Khan Award: $1 million prize recognizes world's best new community architecture". KTVZ. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

Sources

[edit]- "Middle East Delights of Muslim architecture – BBC News, October 10, 1998". 10 October 1998. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- "A Counterpoint of Cloth and Stone, Clark, A., Saudi Aramco World, Nov/Dec 1999: 2–7". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- "Elegant Solutions, Swan, S., Saudi Aramco World, Jul/Aug 1999: 16–27". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- "Shaking Up Architecture, Lawrence, L. A., Saudi Aramco World, Jan/Feb 2001: 6–19". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2006.

- Gerry Loughran, Better by design, 1989, Saudi Aramco World

Further reading

[edit]- Sardar, Zahid (1 March 2003). "Aga Khan Award for Architecture Building cultural bridges". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- Sardar, Zahid (9 March 2005). "Culture's winning ways: The Aga Khan Award for Architecture's latest triumphs shows Islam's best". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- "7 Projects Receive The 2004 Aga Khan Award for Architecture". ARCHI-TECH magazine. Stamats Business Media. November 2004. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

![Eco-Dome[47] sandbag shelter under construction in Djibouti](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Flickr_-_DVIDSHUB_-_New_eco-dome_signals_changes_for_local_village_%28Image_10_of_10%29.jpg/120px-Flickr_-_DVIDSHUB_-_New_eco-dome_signals_changes_for_local_village_%28Image_10_of_10%29.jpg?auto=webp)