82 G. Eridani

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Eridanus |

| Right ascension | 03h 19m 55.651s[1] |

| Declination | −43° 04′ 11.22″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 4.254[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G6 V[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.22[4] |

| B−V color index | +0.71[4] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 87.76±0.13[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 3035.017 mas/yr[1] Dec.: 726.964 mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 165.5242 ± 0.0784 mas[1] |

| Distance | 19.704 ± 0.009 ly (6.041 ± 0.003 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 5.34[2] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.85±0.04[5] 0.91[6] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.90±0.03[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.69±0.03[5][a] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.46±0.10[5] cgs |

| Temperature | 5473±48[6] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.38±0.06[5] dex |

| Rotation | 33.19±3.61 days[7] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 4.0[8] km/s |

| Age | 5.76±0.66,[7] 11.3[2] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | The star |

| planet b | |

| planet c | |

| planet d | |

| Exoplanet Archive | data |

| ARICNS | data |

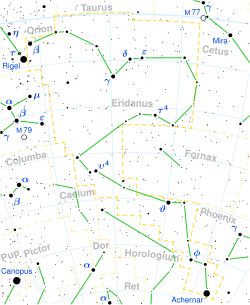

82 G. Eridani (HD 20794, HR 1008, e Eridani) is a star 19.7 light-years (6.0 parsecs) away from Earth in the constellation Eridanus. It is a main-sequence star with a stellar classification of G6 V, and it hosts a system of at least three planets and a dust disk.

Observation

[edit]In the southern-sky catalog Uranometria Argentina, 82 G. Eridani (often abbreviated to 82 Eridani)[9] is the 82nd star listed in the constellation Eridanus.[10] The Argentina catalog, compiled by the 19th-century astronomer Benjamin Gould, is a southern celestial hemisphere analog of the more famous Flamsteed catalog, and uses a similar numbering scheme. 82 G. Eridani, like other stars near the Sun, has held on to its Gould designation, even while other more distant stars have not.[citation needed]

Properties

[edit]This star is slightly smaller and less massive than the Sun, making it marginally dimmer than the Sun in terms of luminosity; it is about a third more luminous than Tau Ceti or Alpha Centauri B. The projected equatorial rotation rate (v sin i) is 4.0 km/s,[8] compared to 2.0 km/s for the Sun. However, this value is likely overestimated and explained by the limitation of the spectrograph used. When observed by HARPS, a v sin i smaller than 2 km/s is found, compatible with a slow-rotating or inclined star. Such observation would also match the lack of a reliable rotational period detection and the absence of any magnetic cycle.[11]

82 G. Eridani is a high-velocity star—it is moving quickly compared to the average—and hence is probably a member of Population II, generally older stars whose motions take them well outside the plane of the Milky Way. Like many other Population II stars, 82 G. Eridani is somewhat metal-deficient (though much less deficient than many), and is older than the Sun.[12] It has a relatively high orbital eccentricity of 0.42 about the galaxy, ranging between 3.52 and 8.41 kiloparsecs from the core.[2] Its age is estimated at 5.76 billion years, based on its chromospheric activity indicator,[7] but other estimates suggest ages close or higher to the age of the Universe.[5][2]

This star is located in a region of low-density interstellar matter (ISM), so it is believed to have a large astropause that subtends an angle of 6″ across the sky. Relative to the Sun, this star is moving at a space velocity of 101 km/s, with the bow shock advancing at more than Mach 3 through the ISM.[13]

Planetary system

[edit]An infrared excess was discovered around the star by the Infrared Space Observatory at 60 μm,[14] but was not later confirmed by the Spitzer Space Telescope, in 2006. However, in 2012, a dust disk was found around the star,[15] by the Herschel Space Observatory. While not well-constrained, if assumed to have a similar composition to 61 Virginis' dust disk, it has a semi-major axis of 24 AU.[16]

On August 17, 2011, European astronomers announced the discovery of three planets orbiting 82 G. Eridani. The mass range of these planets classifies them as super-Earths; objects with only a few times the Earth's mass. These planets were discovered by precise measurements of the radial velocity of the star, with the planets revealing their presence by their gravitational displacement of the star during each orbit. None of the planets display a significant orbital eccentricity. However, their orbital periods are all 90 days or less, indicating that they are orbiting close to the host star. The equilibrium temperature for the most distant planet, based on an assumed Bond albedo of 0.3, would be about 388 K (115 °C); significantly above the boiling point of water.[7]

At the time of planet c's detection, it exerted the lowest gravitational perturbation. There was also a similarity noted between its orbital period and the rotational period of the star. For these reasons the discovery team were somewhat more cautious regarding the verity of its candidate planet status than for the other two.[7]

Using the TERRA algorithm, developed by Guillem Anglada-Escudé and R. Paul Butler in 2012, to describe better and filter out noise interference to extract more precise radial velocity measurements, a team of scientists led by Fabo Feng, in 2017, provided evidence for up to three more planets. One such candidate, of Neptune mass, 82 G. Eridani f, may orbit in the habitable zone of the star. The team also believe that, using these noise reduction techniques, they are able to better quantify the descriptions for the earlier 3 exoplanets, but only have weak evidence of 82 G. Eridani c.[17]

A study in 2023 could only confirm planets b & d, and did not significantly detect the other planet candidates. In particular, the statistical significance of planet c would be expected to increase with additional data; the fact that this has not happened casts doubt on its existence. The 40-day radial velocity signal may instead be tied to the stellar rotation. The additional three candidates found in 2017 (e, f, g) could not be confirmed or refuted.[18]: 23, 44 Another 2023 study also only confirmed b & d out of the previous planet candidates (referring to them as b & c), but also detected a potential third planet farther from the star than any of the previous candidates, on an eccentric orbit partially within the habitable zone.[11] A 2024 study confirms this habitable zone planet.[19]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hot dust | ≲0.1 AU | — | — | |||

| b | ≥2.0±0.2 M🜨 | 0.13±0.01 | 18.32±0.01 | 0.09+0.08 −0.06 |

— | — |

| c | ≥4.7±0.4 M🜨 | 0.37±0.01 | 89.58+0.09 −0.10 |

0.13±0.07 | — | — |

| d | ≥6.6+0.6 −0.7 M🜨 |

1.36±0.03 | 644.6+9.9 −7.7 |

0.40±0.07 | — | — |

| Dust disk | 22–27 AU | 50° | — | |||

Planned observation missions

[edit]82 G. Eridani (GJ 139) was picked as a Tier 1 target star for NASA's proposed Space Interferometry Mission (SIM) mission to search for terrestrial-sized or larger planets,[20] which was cancelled in 2010.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Calculated, using 82 G. Eridani's absolute bolometric magnitude (Mbol) or 5.15±0.05 in the following equation, with respect to the Sun's Mbol of 4.74:

100.4 • (4.74 - Mbol)

The error bar is then calculated using the magnitude's upper and lower values, or 5.05 and 5.20. - ^ The Cretignier et al. 2023 reference used here refers to the 90-day planet as "c" and the new 640-day planet as "d".[11] Previous publications refer to the 90-day planet as "d", with "c" referring to a 40-day candidate that is likely a false positive.[18] Additional candidates found by Feng et al. 2017[17] are not included here as they are not detected by more recent studies.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Vallenari, A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2023). "Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 674: A1. arXiv:2208.00211. Bibcode:2023A&A...674A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202243940. S2CID 244398875. Gaia DR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e Holmberg, J.; Nordstrom, B.; Andersen, J. (July 2009), "The Geneva-Copenhagen survey of the solar neighbourhood. III. Improved distances, ages, and kinematics", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 501 (3): 941–947, arXiv:0811.3982, Bibcode:2009A&A...501..941H, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811191, S2CID 118577511

- ^ Keenan, Philip C; McNeil, Raymond C (1989). "The Perkins Catalog of Revised MK Types for the Cooler Stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 71: 245. Bibcode:1989ApJS...71..245K. doi:10.1086/191373.

- ^ a b c "LHS 19 -- High proper-motion Star", SIMBAD, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg, retrieved 2007-07-26

- ^ a b c d e f Bernkopf, J.; Chini, R.; Buda, L. -S.; Dembsky, T.; Drass, H.; Fuhrmann, K.; Lemke, R. (2012-09-01). "Characteristics of the closest known G-type exoplanet host 82 Eri". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 425 (2): 1308–1311. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.425.1308B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21534.x. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ a b Luck, R. Earle (2018-03-01). "Abundances in the Local Region. III. Southern F, G, and K Dwarfs". The Astronomical Journal. 155 (3): 111. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..111L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aaa9b5. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ a b c d e Pepe, F.; et al. (2011), "The HARPS search for Earth-like planets in the habitable zone: I – Very low-mass planets around HD20794, HD85512 and HD192310", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 534: A58, arXiv:1108.3447, Bibcode:2011A&A...534A..58P, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201117055, S2CID 15088852

- ^ a b Schröder, C.; Reiners, Ansgar; Schmitt, Jürgen H. M. M. (January 2009), "Ca II HK emission in rapidly rotating stars. Evidence for an onset of the solar-type dynamo" (PDF), Astronomy and Astrophysics, 493 (3): 1099–1107, Bibcode:2009A&A...493.1099S, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810377[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kostjuk, N. D. (2004). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: HD-DM-GC-HR-HIP-Bayer-Flamsteed Cross Index (Kostjuk, 2002)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: IV/27A. Originally Published in: Institute of Astronomy of Russian Academy of Sciences (2002). 4027. Bibcode:2004yCat.4027....0K.

- ^ Gould, Benjamin Apthorp (1879), Uranometria Argentina: brightness and position of every fixed star, down to the seventh magnitude, within one hundred degrees of the South Pole, Resultados, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Observatorio Astronómico, vol. 1, Observatorio Nacional Argentino, pp. 159–160 Coordinates are for the 1875 equinox.

- ^ a b c d Cretignier, M.; Dumusque, X.; et al. (August 2023). "YARARA V2: Reaching sub-m s−1 precision over a decade using PCA on line-by-line radial velocities". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 678: A2. arXiv:2308.11812. Bibcode:2023A&A...678A...2C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347232. S2CID 261076243.

- ^ Hearnshaw, J. B. (1973), "The iron abundance of 82 Eridani", Astronomy and Astrophysics, 29: 165–170, Bibcode:1973A&A....29..165H

- ^ Frisch, P. C. (1993), "G-star astropauses - A test for interstellar pressure", Astrophysical Journal, 407 (1): 198–206, Bibcode:1993ApJ...407..198F, doi:10.1086/172505

- ^ Decin, G.; et al. (May 2000). "The Vega phenomenon around G dwarfs". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 357: 533–542. Bibcode:2000A&A...357..533D.

- ^ Wyatt, M. C.; et al. (2012). "Herschel imaging of 61 Vir: implications for the prevalence of debris in low-mass planetary systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 424 (2): 1206. arXiv:1206.2370. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.424.1206W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21298.x. S2CID 54056835.

- ^ a b Kennedy, G. M.; Matra, L.; Marmier, M.; Greaves, J. S.; Wyatt, M. C.; Bryden, G.; Holland, W.; Lovis, C.; Matthews, B. C.; Pepe, F.; Sibthorpe, B.; Udry, S. (2015). "Kuiper belt structure around nearby super-Earth host stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 449 (3): 3121. arXiv:1503.02073. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.449.3121K. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv511. S2CID 53638901.

- ^ a b Feng, F.; Tuomi, M.; Jones, H.R.A. (September 2017). "Evidence for at least three planet candidates orbiting HD 20794". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 605 (103): 11. arXiv:1705.05124. Bibcode:2017A&A...605A.103F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201730406. S2CID 119084078.

- ^ a b Laliotis, Katherine; Burt, Jennifer A.; et al. (April 2023). "Doppler Constraints on Planetary Companions to Nearby Sun-like Stars: An Archival Radial Velocity Survey of Southern Targets for Proposed NASA Direct Imaging Missions". The Astronomical Journal. 165 (4): 176. arXiv:2302.10310. Bibcode:2023AJ....165..176L. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/acc067.

- ^ Nari, N.; Dumusque, X.; Hara, N. C.; Mascareño, A. Suárez; Cretignier, M.; Hernández, J. I. González; Stefanov, A. K.; Passegger, V. M.; Rebolo, R.; Pepe, F.; Santos, N. C.; Cristiani, S.; Faria, J. P.; Figueira, P.; Sozzetti, A. (2024-11-04). "Revisiting the multi-planetary system of the nearby star HD 20794. Confirmation of a low-mass planet in the habitable zone of a nearby G-dwarf". Astronomy & Astrophysics. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202451769. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ McCarthy, Chris (2005). "SIM Planet Search Tier 1 Target Stars". San Francisco State University. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Ramírez, I.; Allende Prieto, C.; Lambert, D. L. (2013-02-01). "Oxygen Abundances in Nearby FGK Stars and the Galactic Chemical Evolution of the Local Disk and Halo". The Astrophysical Journal. 764 (1): 78. arXiv:1301.1582. Bibcode:2013ApJ...764...78R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/764/1/78. ISSN 0004-637X.

External links

[edit]- "82 Eridani". SolStation. Retrieved 2005-11-03.