Bell v. Maryland

| Bell v. Maryland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued October 14 – October 15, 1963 Decided June 22, 1964 | |

| Full case name | Robert Mack Bell et at., v. Maryland |

| Citations | 378 U.S. 226 (more) 84 S. Ct. 1814; 12 L. Ed. 2d 822 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 227 Md. 302, 176 A.2d 771 (1962) (upholding conviction) |

| Subsequent | 236 Md. 356, 204 A.2d 54 (1964) (upholding conviction); 236 Md. 356, rehearing granted and conviction reversed (April 9, 1965). |

| Holding | |

| The Supreme Court vacated the judgment and remanded to the Court of Appeals of Maryland to allow consideration whether a change in state law should result in dismissal of the convictions. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Brennan, joined by Warren, Clark, Stewart, Goldberg |

| Concurrence | Douglas |

| Concurrence | Goldberg, joined by Warren, Douglas |

| Dissent | Black, joined by Harlan, White |

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964), provided an opportunity for the Supreme Court of the United States to determine whether racial discrimination in the provision of public accommodations by a privately owned restaurant violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution. However, due to a supervening change in the state law, the Court vacated the judgment of the Maryland Court of Appeals and remanded the case to allow that court to determine whether the convictions for criminal trespass of twelve African American students should be dismissed.[1]

Background

[edit]In 1960, twelve African American students were part of a group, which conducted a sit-in at Hooper's restaurant in downtown Baltimore, Maryland, where they had been refused service. When they refused to leave, they were arrested, convicted of criminal trespass in the Circuit Court of Baltimore City, and fined $10. They appealed their convictions to the highest court in Maryland, the Court of Appeals, which upheld their conviction. They then appealed to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari.

Decision

[edit]Although the Court had been briefed regarding whether the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment were applicable to the restaurant, the majority opinion noted that both the City of Baltimore and Maryland had passed laws against racial discrimination by an owner or operator of a place of public accommodation. The state antidiscrimination statute went further and forbade discrimination in public accommodations for sleeping or eating on the basis of race, creed, color, or national origin. The opinion, consistent with the Court's practice when a significant supervening change in law has occurred, vacated the criminal convictions of the students and remanded the case back to the Maryland Court of Appeals to allow it to consider whether the convictions should be dismissed under the current state law. The Court noted that the common law of Maryland held that when the legislature has repealed a criminal statute or otherwise makes conduct that once was a crime legal, a state court would dismiss any pending criminal proceeding charging such conduct. Lastly, the majority opinion noted that Maryland had a savings statute, which preserves criminal convictions and penalties when criminal statutes are amended, reenacted, revised, or repealed unless the legislation implementing the amendment, reenactment, revision, or repeal expressly provided that such convictions or penalties should be reduced or vacated. However, the Court did not believe that the Maryland savings statute would be applicable to the new antidiscrimination statute.

The concurring opinion by Justice Goldberg states that while the majority opinion is correct, if the case were properly before the Court, under the Fourteenth Amendment, the cases should be vacated. The concurring opinion by Justice Douglas would reach the merits of the case and vacate the convictions with direction that the cases be dismissed. The dissenting opinion by Justice Black would affirm the decision of the Maryland Court of Appeals that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to the convictions for criminal trespass on private property.

Critical response

[edit]Bell v. Maryland was one of five cases involving segregation protests decided on June 22, 1964. The other four cases were Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130 (1964), Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964), Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964), and Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 (1964). The Supreme Court did not reach the merits of any argument addressing in any of those cases on whether private actions of segregation that were enforced by state courts were a state action violating the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[2] The decisions were announced two days after the United States Senate ended a filibuster and passed the bill that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964,[2] which outlawed segregation in public accommodations. It has been suggested that the Supreme Court refrained from reaching the merits in those cases in consideration of the Act to avoid eliminating the basis for passing the legislation.[2]

Subsequent developments

[edit]The convictions were vacated by the Court of Appeals of Maryland on April 9, 1965, and the City of Baltimore was directed to pay the cost of the appeal to the Supreme Court of $462.93 to Robert M. Bell,[3] the named defendant in the case. Robert Bell's listing as the named defendant was accidental as his name was alphabetically first among the thirteen arrested students.[4]

The Bell case was remanded by the Supreme Court essentially to determine whether a pending conviction for activity in protest of segregation should be vacated when the segregated activity became proscribed by later state legislation. The Supreme Court later answered this question affirmatively in Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 (1964), for prosecutions for activities protected by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

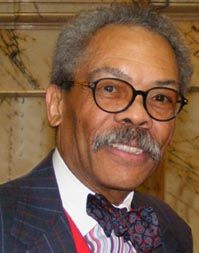

Robert M. Bell later became an attorney and in 1984 was appointed as a judge of the Maryland Court of Appeals, a court that had ruled against him in Bell v. Maryland, and where he became its Chief Judge in 1996. That court's prior Chief Judge was Robert C. Murphy, who when he had been a deputy attorney general attempted to uphold Bell's trespassing conviction for the sit-in and is listed by name on the state's brief to the Supreme Court in the case.[5]

The Maryland State Archives, as a teaching tool, has posted all of the legal papers associated with the case from each of its phases online.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964).

- ^ a b c Webster, McKenzie. "The Warren Court's Struggle With the Sit-In Cases and the Constitutionality of Segregation in Places of Public Accommodations". Journal of Law and Politics. 17 (Spring 2001): 373–407.

- ^ Court of Appeals of Maryland order on rehearing (April 9, 2008)

- ^ Reynolds, William L. (2002). "The Legal History of the Great Sit-In Case of Bell v. Maryland". Maryland Law Review. 61: 761–794.

- ^ 12 L. Ed.2d 1335-36 (Briefs of Counsel in Bell v. Maryland)

- ^ "Desegregation of Maryland's Restaurants: Robert Mack Bell v. Maryland". Teaching American History in Maryland: Documents for the Classroom. Maryland State Archives. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved May 26, 2008.

External links

[edit]- Text of Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226 (1964) is available from: Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- 1964 in Maryland

- 1964 in United States case law

- Anti-black racism in Maryland

- History of racism in Maryland

- United States equal protection case law

- United States racial desegregation case law

- United States Supreme Court cases

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Warren Court

- Legal history of Maryland

- Civil rights movement case law

- Sit-in movement