February 28 Popular Leagues

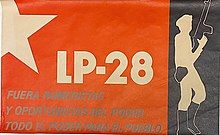

The February 28 Popular Leagues (Spanish: Ligas Populares 28 de Febrero, abbreviated LP-28) was a mass movement in El Salvador. LP-28 was launched in September 1977 by the People's Revolutionary Army (ERP), functioning as its mass front.[1][2][3][4] The name referred to the February 28, 1977 massacre of ERP supporters, killed at Plaza Libertad in San Salvador during a protest against electoral fraud in the 1977 Salvadoran presidential election.[5][6] LP-28 had some 5,000 to 10,000 members.[7][8] Its following was largely based among peasants in Morazán Department.[8] Leoncio Pichinte was the general secretary of LP-28.[9]

ERP and the formation of LP-28

[edit]In the lead-up to the Salvadoran Civil War the mass mobilization of ERP was weaker than that of other guerrilla groups, as ERP had a more militaristic outlook.[7] ERP had lost its previous mass front, the Unified Popular Action Front (FAPU), in an internal split in 1976.[7] LP-28 was launched in response to the advances in mass organizations of its competitors among the guerrilla movements.[7] In reaction to the electoral fraud and repression against the progressive sectors in the Catholic church, most of the Ecclesiastic Base Communities (CEB) in Morazán Department joined LP-28.[1] In November 1977 the military forces had arrested and tortured Father Miguel Ventura in Morazan Department, but LP-28 organized mass protests in the area and managed to secure his release and allow Ventura to go into exile.[1]

1979 coup

[edit]LP-28 took a militant stance against the October 15, 1979 coup d'état,[8] taking actions to draw attention to the situation in El Salvador, such as occupations of embassy buildings, government installations and churches.[1][7] LP-28, along with ERP, issued a call for a nation-wide insurrection.[10] On October 29, 1979, government forces opened fire on an LP-28 rally in Morazán Department, killing 29 people.[8]

1979 congress

[edit]The movement held its first congress on November 27, 1979, which affirmed the overthrow of the military junta and the establishment of a socialist society as the goals of the movement.[8] The congress was baptized 'Irma Elena Contreras'.[8] Some 3,000 LP-28 supporters attended the event.[8] The meeting was addressed by guerrilla leader Ana Guadalupe Martínez Menéndez.[8] The People's Revolutionary Bloc (BPR) sent a small delegation to the LP-28 congress.[8] The BPR delegation was led by Juan Chacón, who in his intervention at the event made a call for unity.[8] FAPU did not attend the LP-28 congress, as there was still hostility after the ERP killing of FAPU leader Roque Dalton.[8]

CRM and FDR

[edit]On January 11, 1980, LP-28, BPR and FAPU issued a joint call for insurrection.[11] LP-28, BPR and FAPU organized a joint protest on January 22, 1980, which was met with violence from the state.[11] Subsequently, LP-28, BPR and FAPU formed the Revolutionary Mass Coordination (CRM).[11][12] CRM later merged into the Revolutionary Democratic Front (FDR), LP-28 was given one of seven slots in the FDR leadership - where it was represented by Pichinte.[13][14]

Member organizations

[edit]LP-28 was constituted by

- the "Heroes of October 29" Popular Peasant Leagues (Ligas Populares Campesinas "Héroes del 29 de octubre", LPC-28)

- the Secondary Students Popular Leagues "Edwin Arnoldo Contreras" (Ligas Populares Estudiantiles de Secundarias "Edwin Arnoldo Contreras", LPES)

- the Popular University Leagues "Mario Nelson Alfaro" (Ligas Populares Universitarias "Mario Nelson Alfaro", LPU)

- the Popular Workers Leagues "Marco Antonio Solís" (Ligas Populares Obreras "Marco Antonio Solís", LPO-28)

- the LP-28 Barrio and Colony Committees (Comités de Barrios y Colonias LP-28, CB-LP-28)

- the Association of Market Users and Workers of El Salvador (Asociación de Usuarios y Trabajadores de los Mercados de El Salvador, ASUTRAMES).[2][15][16]

In exile

[edit]LP-28 was present in Salvadoran diaspora, for example it had presence in Costa Rica.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Jeffrey Gould (2021). Entre el bosque y los árboles: Utopías Menores en El Salvador, Nicaragua y Uruguay. transcript Verlag. p. 45. ISBN 9783839456408.

- ^ a b Marta Harnecker (1991). Con la mirada en alto: historia de las Fuerzas Populares de Liberación Farabundo Martí a través de entrevistas con sus dirigentes. Tercera Prensa. pp. 150, 309. ISBN 9788487303098.

- ^ Carlos María Vilas (1994). Mercado, estados y revoluciones: Centroamérica, 1950-1990. UNAM. p. 99. ISBN 9789683639011.

- ^ Daniel Camacho (1989). Los Movimientos populares en América Latina. Siglo XXI. p. 103. ISBN 9789682315282.

- ^ Ralph Sprenkels (2018). After Insurgency: Revolution and Electoral Politics in El Salvador. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 9780268103286.

- ^ Santiago Mata (2015). Monseñor Óscar Romero: Pasión por la Iglesia. Palabra. ISBN 9788490612569.

- ^ a b c d e Jocelyn Viterna (2013). Women in War: The Micro-processes of Mobilization in El Salvador. Oxford University Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-19-984363-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jeffrey L. Gould (2019). Solidarity Under Siege. Cambridge University Press. pp. xvii, 91, 93, 107. ISBN 9781108419192.

- ^ El País. Las Ligas Populares salvadoreñas ocupan la embajada de Panamá

- ^ Charles D. Brockett (2005). Political Movements and Violence in Central America. Cambridge University Press. p. 302. ISBN 9780521600552.

- ^ a b c Charles J. Beirne, S.J. (2013). Jesuit Education and Social Change in El Salvador. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781135597665.

- ^ Orlando J. Perez (2016). Historical Dictionary of El Salvador. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 121. ISBN 9780810880207.

- ^ Thomas P. Anderson (1988). Politics in Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 9780275928834.

- ^ Diario Co Latino. 37 años de la dirigencia del Frente Democrático Revolucionario

- ^ Oscar Martinez Peñate. El Salvador del Conflicto Armado a la Negociacion 1979 1989. Editorial Nuevo Enfoque. p. 27. ISBN 9789992380024.

- ^ El Salvador: el amanecer de un pueblo. Centro de Estudios y Difusión Social. 1983. p. 25.

- ^ Tanya Basok (1993). Keeping Heads Above Water: Salvadoran Refugees in Costa Rica. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 52. ISBN 9780773509771.