Triptane

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2,2,3-Trimethylbutane[1] | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| 1730756 | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.680 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1206 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C7H16 | |||

| Molar mass | 100.205 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | 0.693 g mL−1 | ||

| Melting point | −26 to −24 °C; −15 to −11 °F; 247 to 249 K | ||

| Boiling point | 80.8 to 81.2 °C; 177.3 to 178.1 °F; 353.9 to 354.3 K | ||

| Vapor pressure | 23.2286 kPa (at 37.7 °C) | ||

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

4.1 nmol Pa−1 kg−1 | ||

| -88.36·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.389 | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

213.51 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

292.25 J K−1 mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−238.0 – −235.8 kJ mol−1 | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−4.80449 – −4.80349 MJ mol−1 | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H225, H302, H305, H315, H336, H400 | |||

| P210, P261, P273, P301+P310, P331 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −7 °C (19 °F; 266 K) | ||

| 450 °C (842 °F; 723 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | 1–7% | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanes

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

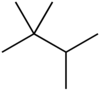

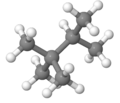

Triptane, or 2,2,3-trimethylbutane, is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C7H16 or (H3C-)3C-C(-CH3)2H. It is therefore an alkane, specifically the most compact and heavily branched of the heptane isomers, the only one with a butane (C4) backbone.

It was first synthesized in 1922 by Belgian chemists Georges Chavanne (1875–1941) and B. Lejeune, who called it trimethylisopropylmethane.[2][3]

Due to its high octane rating (112–113 RON, 101 MON[4][5]) triptane was produced on alkylation units starting from 1943[6] for use as an anti-knock additive in gasoline. It was extensively researched for this role and received the modern name in the late 1930s at a joint laboratory of NACA, National Bureau of Standards, US Army Air Corps and the Bureau of Aeronautics.[7]

As of 2011, it was not a significant component of US automobile gasoline, present only in trace amounts (0.05–0.1%).[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Triptan - Compound Summary". PubChem Compound. USA: National Center for Biotechnology Information. 26 March 2005. Identification and Related Records. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Chavanne, G.; Lejeune, B. (March 1922). "Un nouvel heptane : le triméthylisopropylméthane". Bulletin de la Société Chimique de Belgique. 31 (3): 99–102 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ https://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?Source=1922CHA%2FLEJ98

- ^ Nash, Connor P.; Dupuis, Daniel P.; Kumar, Anurag; Farberow, Carrie A.; To, Anh T.; Yang, Ce; Wegener, Evan C.; Miller, Jeffrey T.; Unocic, Kinga A.; Christensen, Earl; Hensley, Jesse E.; Schaidle, Joshua A.; Habas, Susan E.; Ruddy, Daniel A. (2022-02-01). "Catalyst design to direct high-octane gasoline fuel properties for improved engine efficiency". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 301: 120801. Bibcode:2022AppCB.30120801N. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120801. ISSN 0926-3373. OSTI 1827631.

- ^ Perdih, A.; Perdih, F. (2006). "Chemical Interpretation of Octane Number". Acta Chimica Slovenica. S2CID 55494502.

- ^ stason.org, Stas Bekman: stas (at). "10.1 The myth of Triptane". stason.org. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ Annual Report of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1938. p. 28.

- ^ "Hydrocarbon Composition of Gasoline Vapor Emissions from Enclosed Fuel Tanks". nepis.epa.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2011.