One Times Square

| One Times Square | |

|---|---|

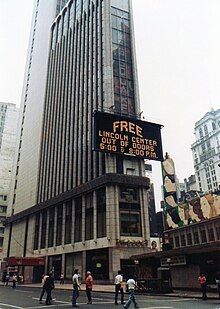

One Times Square in 2017 from one block north. The building is barely visible given the signage. | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | 1 Times Square Manhattan, New York 10036 |

| Coordinates | 40°45′23″N 73°59′11″W / 40.756421°N 73.9864883°W |

| Construction started | 1903 |

| Completed | 1904 |

| Opening | January 1, 1905 |

| Owner | Jamestown L.P. and Sherwood Equities |

| Height | |

| Antenna spire | 417 ft (127 m) |

| Roof | 363 ft (111 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 25 |

| Floor area | 110,599 sq ft (10,275.0 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz and Andrew C. McKenzie |

| Developer | The New York Times |

| Website | |

| onetimessquare | |

| References | |

| [1][2][3] | |

One Times Square (also known as 1475 Broadway, the New York Times Building, the New York Times Tower, the Allied Chemical Tower or simply as the Times Tower) is a 25-story, 363-foot-high (111 m) skyscraper on Times Square in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Designed by Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz in the neo-Gothic style, the tower was built in 1903–1904 as the headquarters of The New York Times. It takes up the city block bounded by Seventh Avenue, 42nd Street, Broadway, and 43rd Street. The building's design has been heavily modified throughout the years, and all of its original architectural detail has since been removed. One Times Square's primary design features are the advertising billboards on its facade, added in the 1990s. Due to the large amount of revenue generated by its signage, One Times Square is one of the most valuable advertising locations in the world.

The surrounding Longacre Square neighborhood was renamed "Times Square" during the tower's construction, and The New York Times moved into the tower in January 1905. Quickly outgrowing the tower, eight years later, the paper's offices and printing presses moved to nearby 229 West 43rd Street. One Times Square remained a major focal point of the area due to its annual New Year's Eve "ball drop" festivities and the introduction of a large lighted news ticker near street-level in 1928. The Times sold the building to Douglas Leigh in 1961. Allied Chemical then bought the building in 1963 and renovated it as a showroom. Alex M. Parker took a long-term lease for the entire building in October 1973, buying it two years later. One Times Square was sold multiple times in the 1980s and continued to serve as an office building.

The financial firm Lehman Brothers acquired the building in 1995, adding billboards to take advantage of its prime location within Times Square. Jamestown L.P. has owned the building since 1997. In 2017, as part of One Times Square's redevelopment, plans were announced to construct a new Times Square museum, observation deck, and a new entrance to the Times Square–42nd Street subway station. Jamestown started a $500 million renovation of the building in 2022. The renovation will add an observation deck, a museum space, and a glass exterior, and is scheduled to be completed in 2025.

Site

[edit]One Times Square is at the southern end of Times Square in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It takes up the city block bounded by Seventh Avenue to the west, 42nd Street to the south, Broadway to the east, and 43rd Street to the north.[4][5] The land lot is trapezoidal and covers 5,400 sq ft (500 m2).[4] The full-block site has a frontage of 137.84 feet (42.01 m) to the west, 58.33 feet (18 m) to the south, 143 feet (44 m) to the east, and 20 feet (6.1 m) to the north.[6][7] The shape of the site arises from Broadway's diagonal alignment relative to the Manhattan street grid.[8][a] The building's address was originally 1475 Broadway, but it was changed to 1 Times Square in 1966.[9] The current address is a vanity address assigned by the government of New York City. The addresses around Times Square are not assigned in any particular order; for example, 2 Times Square is several blocks away from 1 Times Square.[10]

Nearby buildings include 1501 Broadway to the north, 1500 Broadway to the northeast, 4 Times Square to the east, The Knickerbocker Hotel to the southeast, the Times Square Tower to the south, 5 Times Square to the southwest, and 3 Times Square to the west.[4][5] An entrance to the New York City Subway's Times Square–42nd Street station, served by the 1, 2, 3, 7, <7>, N, Q, R, W, and S trains, is directly adjacent to the building. There is also an entrance to the 42nd Street–Bryant Park/Fifth Avenue station, served by the 7, <7>, B, D, F, <F>, and M trains, less than a block east.[11]

Prior to the construction of what is now One Times Square, the northern end of the site had been part of the estate of Amos R. Eno, which had sold the site in 1901 to the Subway Realty Company.[12] The southern end contained the Pabst Hotel,[13] which had been built on land leased from Charles Thorley.[14] The southeast corner of the building originally contained a plaque containing Thorley's name, as he had required that his name be placed on any building that was constructed on the site.[15][16] The New York Times Company bought the site in 1927, four years after Thorley died, but the plaques remained until 1963.[15]

History

[edit]Times ownership

[edit]Newspaper publisher Adolph Ochs purchased The New York Times in 1896.[17] The paper was then headquartered at 41 Park Row in Lower Manhattan, within the city's Newspaper Row. The Times expanded greatly under Ochs's leadership,[18] prompting him to acquire land for a new headquarters in Longacre Square.[19] In August 1902, Ochs purchased the former Eno ground from the Subway Realty Company and obtained a long-term lease from Charles Thorley on the ground under the Pabst Hotel.[13][20] At the time, the first line of the New York City Subway was being constructed through the site, spurring commercial growth in the surrounding neighborhood.[21] In deciding to relocate to Longacre Square, the Times cited the fact that the New York City Subway's Times Square station would be directly adjacent to the new building, thus allowing the paper to expand its circulation.[13][22]

Headquarters

[edit]

In mid-1902, the Times hired architect Cyrus L. W. Eidlitz to draw up plans for its skyscraper headquarters at Longacre Square.[22][23] Site clearing began in December 1902 and was completed within two months. Afterward, workers began constructing the building's concrete, brickwork, and ironwork in mid-1903.[23] By the end of the year, the steel frame was being constructed at a rate of three stories per week.[24] Ochs's 11-year-old daughter Iphigene Bertha Ochs laid the building's cornerstone on January 18, 1904, after the steel frame had been completed.[25][26] Ochs successfully persuaded the New York City Board of Aldermen to rename the surrounding area after the newspaper, and Longacre Square was renamed Times Square in April 1904.[27] Workers were installing interior finishes by the next month.[23] Construction was temporarily halted that August when seventeen workers' unions went on strike.[28][29] According to the Times, the building's completion was delayed by 299 days due to various strikes during the project, as well as inclement weather.[30]

Prior to the building's completion, in November 1904, the Times used searchlights on the facade to display the results of the 1904 United States presidential election. The Times indicated which candidate won by flashing searchlights on different sides of the building.[31] The New York Times officially moved into the building on January 1, 1905.[32] To help promote the new headquarters, the Times held a New Year's Eve event on December 31, 1904, welcoming the year 1905 with a fireworks display set off from the roof of the building at midnight.[33][34][35] The event was a success, attracting 200,000 spectators, and was repeated annually through 1907.[34][35] Hegeman & Company leased most of the ground level in mid-1905, opening a drug store within that space.[36] The same year, the paper started operating a stereopticon machine on the north side of the building, displaying news bulletins.[37] In addition, the Times experimented with transmitting music and telephone messages to the top of its tower in 1907.[38]

In 1908, Ochs replaced the fireworks display with the lowering of a lit ball down the building's flagpole at midnight, patterned off the use of time balls to indicate a certain time of day.[35][39][40] By then, the New York City government had banned the fireworks displays, which were detonated directly over the crowd and, thus, posed a danger.[41] The "ball drop" was directly inspired by a time ball atop the Western Union Telegraph Building in lower Manhattan.[42] By then, Times Square had become a popular venue for New Year's celebrations.[43] The ball drop is still held atop One Times Square, attracting an average of one million spectators yearly.[35][39][40] The Times Tower was also used for telegraph experiments,[44] and its searchlights continued to display election results, including those for the 1908 United States presidential election.[45] The building's roof attracted visitors such as French author Pierre Loti, who called the Times Tower "one of the boldest" of New York City's skyscrapers,[46] and Jamalul Kiram II, the Sultan of Sulu.[47]

Times relocation and office use

[edit]

There was so little space on the Times Tower site that its mechanical basements had to descend as much as 65 ft (20 m). By the early 1910s, the Times Square area had become densely developed with restaurants, theaters, hotels, and office buildings.[48] Despite the dearth of space, a Times booklet said: "It did not occur to anyone to suggest that the [Times] should desert Times Square."[19][49] On February 2, 1913, eight years after it moved to One Times Square,[50] the Times moved its corporate headquarters to 229 West 43rd Street,[39][40] where it remained until 2007.[51] Most of the Times's operations quickly moved to the annex, except for the publishing and subscription divisions.[19] The Times retained ownership of the Times Tower and leased out the former space there.[52][53][54] The building continued to be popularly known as the Times Tower for half a century.[55]

The original Times Square Ball above the Times Tower was replaced following the 1919–1920 New Year's celebrations.[34] A neon beacon was installed atop the Times Tower's roof in September 1928.[56] An electromechanical Motograph News Bulletin news ticker, colloquially known as the "zipper", started operating near the base of the building on November 6, 1928,[57][58] after eight weeks of installation.[59] The zipper originally consisted of 14,800 light bulbs, with the display controlled by a chain conveyor system inside the building; individual letter elements (a form of movable type) were loaded into frames to spell out news headlines. As the frames moved along the conveyor, the letters themselves triggered electrical contacts which lit the external bulbs (the zipper was later upgraded to use modern LED technology).[57][60][61] The first headline displayed on the zipper announced Herbert Hoover's victory in that day's presidential election.[53][57] The zipper was used to display other major news headlines of the era, and its content later expanded to include sports and weather updates as well.[53][61]

During the 1940s, the building's basement contained a shooting range occupied by the Forty-third Street Rifle Club.[57] Due to restrictions imposed during World War II, the Times Tower's zipper was powered down in May 1942, marking the first time since its installation that the zipper had shut down.[62] The tower's lights were darkened for the same reason. Consequently, the 1942 New York state election was the first since 1904 for which the tower's lights did not broadcast any election results.[63] The Times reactivated the building's zipper in October 1943,[64][65] but, less than two weeks later, the sign was again deactivated to reduce electricity usage.[65][66] The sign operated intermittently until the end of World War II, when it again ran continuously.[59] On the evening of August 14, 1945, the building's zipper announced Japan's surrender in World War II to a packed crowd in Times Square.[67][68]

Ahead of the 1952 United States presidential election, the Times temporarily installed a 85-foot-tall (26 m) electronic sign on the 4th through 11th stories of the northern facade, displaying each candidate's electoral vote count.[69] The sign was reinstalled on the Times Tower during the 1956 United States presidential election.[70] The tower's ball was also replaced after the 1954–1955 celebrations.[34] The New York Community Trust installed a plaque outside the building in 1957, designating it as a point of interest and an unofficial "landmark".[71]

Leigh and Allied Chemical ownership

[edit]The Times sold the building to advertising executive and sign designer Douglas Leigh in 1961.[16][72] According to The Wall Street Journal, Leigh had attempted to purchase the Times Tower for 25 years before he succeeded.[73] At the time, there were 110 tenants in the building; the Times only operated the zipper as well as a classified advertising office at ground level. Leigh had planned to construct an exhibition hall within the building.[16][72] One of the Times Tower's subbasement levels caught fire in November 1961, killing three people and injuring 24 others;[74] investigators later determined that the fire had been caused by "careless smoking".[75] The building's zipper was deactivated in December 1962 due to the 1962–1963 New York City newspaper strike, and it did not operate for more than two years.[76]

Leigh sold the building in April 1963 to Allied Chemical, which planned to renovate the building and use it as a sales headquarters and showroom.[73][77] The first three stories would be re-clad in glass and serve as a showroom for nylon products, and the interior would be completely overhauled.[77][78] Benjamin Bailyn of architectural firm Smith Haines Lundberg Waehler designed the renovation.[79] Due to recent changes to New York City zoning laws, it was more economically efficient to renovate the Times Tower than to demolish it, as a new building on the site could not be as tall.[80] Work began in October 1963,[81][82] and the Times Tower's original cornerstone was unsealed in a ceremony in March 1964.[83] Allied Chemical stripped the building to its steel frame,[84] replacing the intricate granite and terracotta facade with marble panels as part of a $10 million renovation.[85] The first panel of the new facade crashed to the ground while it was being installed in August 1964.[86] The modifications occurred one year before the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission gained the power to protect buildings as official landmarks, leading architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable to express opposition to the renovation.[87] Huxtable praised the building as "radical and conservative at the same time", saying that it was full of "vintage structural details".[84]

Allied Chemical reactivated the news zipper on the building's facade in March 1965[76] as part of a joint venture with Life magazine.[88] Allied Chemical turned on four 39-foot-high (12 m) electric signs atop the tower in July 1965.[89] The Times Tower was officially rededicated that December as the Allied Chemical Tower.[90][91] Shortly after the renovation was completed, Allied Chemical's nylon division had outgrown the space, and the building's elevator service was also reportedly unreliable.[92] The Stouffer Foods Corporation also agreed to operate an English-themed restaurant on the 15th and 16th floors.[93] The restaurant, known as Act I, opened in 1966.[94] The United States Postal Service officially changed the building's address from 1475 Broadway to 1 Times Square in September 1966.[9]

Allied Chemical announced in late 1972 that it had placed 1 Times Square for sale.[95][96] By that time, the company no longer needed the surplus space in its namesake tower. Allied Chemical had relocated other workers to Morris Township, New Jersey, during early 1972, and it planned to move its nylon division into smaller space at the nearby 1411 Broadway.[96] The firm wanted to sell the building outright at a minimum price of $7 million.[96][97] It is unknown whether anyone submitted a bid to purchase the building, but Allied Chemical ultimately failed to sell it.[97]

Parker renovations

[edit]

Alex M. Parker took a long-term lease for the entire building in October 1973, with an option to purchase the structure.[97][98] Parker then renamed the building Expo America.[99] He planned to convert 17 of the building's stories into an exhibition hall while also continuing to operate the Act I restaurant.[97] Shortly after buying the building, Parker said: "It is my hope that the activity and excitement generated by Expo America will flow outward through the surrounding area, encouraging others to join in the effort to once again make Times Square a great area."[99] In early 1974, Parker announced that the building's zipper would display only advertising and good news because "I've had it with bad news".[100] According to Parker, it cost him $100,000 a year to operate the zipper.[100] Reuters provided the headlines for the zipper.[101]

Parker exercised his option to buy the building in 1975[101] at a cost of $6.25 million.[102][103][104] He then hired the architectural firm of Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects to redesign the tower with a glass facade and sloping roof.[80][101][105] Under Parker's plan, four stories would be added to the tower, and the facade would be replaced with panels of one-way glass.[106] Parker also planned to host a competition to select a new name for the building.[101][105] This plan was never carried out.[80] Instead, Parker and mayor Abraham Beame officially reopened One Times Square as an exhibition center on March 2, 1976.[107] Spectacolor Inc. installed a new zipper on the building's facade later that year.[80][108] The zipper only operated for a short time before being deactivated entirely in 1977.[67][103][109]

Times Square redevelopment

[edit]Early plans

[edit]The City at 42nd Street Inc. proposed demolishing One Times Square in 1979 as part of a plan to redevelop a section of West 42nd Street near Times Square.[110][111] Parker, who had not been consulted about the proposal, expressed his opposition by calling it "obscene".[110] Another plan for the site, announced in 1981, called for renovating One Times Square into a "potential civic sculpture" with a brightly lit facade.[112] In a plan presented to the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC) in June 1981, architectural firm Cooper Eckstut proposed doubling the height of One Times Square's northern section.[113] Parker had sold the building to the Swiss investment group Kemekod in February 1981.[114] Kemekod sold the tower to TSNY Realty Corporation, an investment group led by Lawrence I. Linksman, in 1982 for $12 million.[104] Linksman promised further renovations to the building, including the possibility of using its north face for signage displays.[102][103][104]

As part of the 42nd Street Redevelopment Project, in 1983, architects Philip Johnson and John Burgee had planned to raze One Times Square and construct four new towers[b] immediately surrounding the site.[114][115] Park Tower Realty, which had been designated as the developer of these towers, offered to buy the building in November 1983. Park Tower planned to demolish the building and transfer the Times Square Ball to the tallest of the four new buildings.[116] A month afterward, TSNY sued Park Tower to prevent the demolition.[114][117] Allan J. Riley acquired the building in 1984 for $16.5 million, at which point the building was almost fully leased.[118] Also in 1984, the Municipal Art Society held an architectural design competition for the site, attracting over 1,380 entrants from 15 nations.[119] That December, the building's owner objected to the ESDC's plans to condemn the site.[120] The city and state governments of New York created a six-member committee in 1985 to discuss the future of One Times Square.[121]

Israel and Calmenson ownership

[edit]

Steven M. Israel and Gary Calmenson paid $18.1 million for the building[122] in December 1985 and leased the building's ticker to local newspaper Newsday the next month.[88][123] The ticker displayed headlines, advertising, and weather from 6 a.m. to midnight each day.[88] Israel started converting 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) on the lower stories into the Crossroads Fashion Center, a retail complex designed by Fernando Williams Associates.[124] By then, Park Tower had begun promoting a plan to replace One Times Square with a seven-story building containing an "open staircase running up its middle and a waterfall running over rough stones at its base".[125] City and state officials debated whether to acquire One Times Square through condemnation for several years, but they canceled these plans in 1988 after failing to reach an agreement.[126]

By 1988, Israel had renovated the first two stories for $1 million. In addition, he converted the 11th floor into an amenity area for the building's tenants; the space contained production rooms, a reception area, and a screening room.[127] At the time, the building was known as One Times Square Plaza.[10] Israel and Calmenson refinanced the building in 1989 with a $30 million loan from French bank Banque Arabe Internationale d'Investissement (BAII), and Cofat & Partners bought an equity stake in the building.[122] By then, the zipper was profitable, leading Israel to say: "We have blank exterior walls that are screaming out to be used."[128] The building's owners negotiated to lease additional advertising space on the building to Newsday, but the deal was canceled.[129] Sony agreed to start operating a Jumbotron on the exterior of the tower in 1990;[130][131] the Jumbotron was upgraded in March 1994.[132]

BAII moved to foreclose on the property in 1991, prompting Israel and Calmenson to file for bankruptcy protection in March 1992.[133][129] At the time, the building had 41 tenants but was half vacant.[133] Israel wanted to avoid a foreclosure, as he would be liable for $2 million in taxes if the building were foreclosed upon.[134] Rebecca Rawson was named as the receiver for the bankrupt property.[67] Israel proposed reducing the building's first mortgage in 1993 to avoid foreclosure, but BAII opposed the plan.[122] Newsday stopped operating the building's ticker on December 31, 1994, and declined to renew its lease, believing that it "[didn't] get very much out of that sign" financially.[67][103][109] Publishing company Pearson PLC agreed to operate the zipper three days before Newsday's lease expired,[135][136] using the zipper for news, announcements, and advertisements of its own products.[137]

Lehman Brothers ownership

[edit]Banque National de Paris (BNP) bought the building at a foreclosure auction in January 1995 for $25.2 million.[138] The financial services firm Lehman Brothers acquired the building shortly afterward for $27.5 million.[139][140] According to the Times, Lehman Brothers had been "ridiculed" for buying the building at that price.[139] Madame Tussauds, a subsidiary of Pearson PLC, had sought to lease space for a museum in One Times Square but could not reach an agreement with the new owner.[140][141] Lehman Brothers felt that it would be economically inefficient to use the tower as an office building because it was so small, so the firm decided to market the tower as a location for advertising. The entire exterior of One Times Square above the ticker was modified to add a grid frame for mounting billboard signs.[142][143][144] Dow Jones & Company started operating the zipper in June 1995,[145][146] and Dow Jones replaced the zipper in mid-1997, donating part of the old zipper to the Museum of the City of New York.[147]

Sony's Jumbotron operated until 1996. Alongside its use for advertising and news, it was also frequently used by the producers of the late-night talk show Late Show with David Letterman, who could display a live feed from its studio on the screen as well. As a cost-saving measure, Sony declined to renew its lease of the space, leading to the subsequent removal of the Jumbotron in June 1996. Due to its frequent use by Late Show, its producer Rob Burnett jokingly considered the removal of the Jumbotron to be "a sad, sad day for New York."[148] The last office tenants moved out of the building in 1996,[139] and the first electronic billboards were installed the same year.[149] In October 1996, Warner Bros. agreed to lease the building and operate a retail store at the base.[150][151][152] The complex would include a four-story restaurant on the roof.[150] Warner Bros. hired Frank O. Gehry to design the store, and Gehry released his plans in early 1997. The proposal called for gutting the lowest eight stories and replacing the facade with a translucent wire mesh.[153][154]

Jamestown ownership

[edit]Late 1990s and 2000s

[edit]Lehman Brothers sold One Times Square in June 1997 to Jamestown L.P. for about $110 million, four times more than what Lehman Brothers had paid for the building just two years earlier.[139][155] Sherwood Equities owned a minority stake in the building and was the leasing agent for the retail space.[156] The Warner Bros. store then opened in April 1998, occupying 15,000 square feet (1,400 m2) on three stories.[157][158] The store was known as "1 Toon Square", a reference to its address.[159] In advance of the 1999–2000 New Year's celebrations, the ball atop One Times Square's roof was replaced once again.[160] After a portion of the building's exterior signs collapsed in March 1999, the New York City Department of Buildings ordered that four of the building's billboards be removed.[161]

Time Warner announced in mid-2001 that it would close the Warner Bros. store that October due to a decline in business.[162][163] Time Warner continued to pay rent for the vacant retail space.[164] In 2002, plans were announced for a 7-Eleven convenience store, the Times Square Brewery, and Two Boots Pizza in One Times Square.[165] However, the planned 7-Eleven store was ultimately canceled.[166] Jamestown then repaired 450 panels on the building's facade in the mid-2000s. During this project, one of the facade's panels fell to the ground in 2004, injuring two pedestrians.[167]

Due to the building's small size, it only housed a single office tenant during the 2000s and 2010s: the production company in charge of the Times Square Ball drop.[168] In early 2006, the lower floors were occupied by a pop-up store operated by J. C. Penney and known as The J C. Penney Experience.[169][170] The pharmacy chain Walgreens leased the entire building in 2007,[171][172] paying $4 million yearly. The chain had previously operated a store in the building for four decades until 1970.[156] Walgreens opened a new flagship store in the space in November 2008.[173][174] As part of the store's opening, Gilmore Group designed a digital sign for the facade, constructed by D3 LED. The 17,000-square-foot (1,600 m2) sign ran diagonally up the western and eastern elevations of the building and contained 12 million LEDs, surpassing the nearby Nasdaq MarketSite sign as the largest LED sign in Times Square.[34][175] The sign operated 20 hours a day and advertised Walgreens's products.[173]

2010s to present

[edit]

In September 2017, Jamestown unveiled plans to use much of its vacant space. Under the proposal, a museum dedicated to the history of Times Square would be built on the 15th through 17th floors, and the 18th floor would contain a new observatory.[176] At the time, the building's billboards had started to become dated because of the increasing popularity of interactive programming.[177] The ground level would also be renovated to provide an expanded entrance to the New York City Subway's Times Square–42nd Street station, directly underneath the building. Work on the subway entrance was originally supposed to be completed in 2018,[176] but the MTA did not start construction on the 42nd Street Shuttle reconstruction project until August 2019.[178][179][180] As part of the redevelopment of One Times Square, a new 20-foot-wide (6.1 m) staircase entrance with a glass canopy, as well as a new elevator entrance, would be built.[178] The new $40 million station entrance, including the elevator, formally opened in May 2022.[181][182]

Jamestown announced in January 2019 that it planned to renovate the building and lease the upper floors, which at the time were completely blocked by billboards. Jamestown also planned to either terminate Walgreens's lease or reduce the size of the pharmacy.[183][184] The Real Deal magazine estimated that Jamestown was earning $23 million per year from the building's billboards.[183] Later that year, the Zipper was removed due to the installation of a new display spanning the entire height of the tower.[185][186][187] The Walgreens store at the building's base had closed permanently by 2022.[188]

Jamestown started renovating 1 Times Square in May 2022 at a cost of $500 million.[189][190] To finance the project, Jamestown received a $425 million mortgage from JPMorgan Chase, a building loan of $88.7 million, and a project loan of $39.8 million.[191][192] S9 Architecture designed the renovation with DeSimone as structural engineers, while AECOM and Tishman Construction were the general contractors. The advertising boards on the northern facade remained in place, but the advertisements on the other three facades were removed. The 1960s marble facade would be removed and replaced with a glass curtain wall.[193] The structure would contain only one story of office space after it reopened; the museum would occupy six stories.[168] Technology companies would be able to lease 12 stories for interactive attractions.[168][177] The building's observation deck would be open year-round, and the Times Square Ball would drop several times a day throughout the year.[177] Jamestown would also install a new elevator to the building's observation deck.[176][177] The building would continue to display ads on its northern facade, and it would host New Year's Eve celebrations during the renovation.[189][190]

The Durst Organization, which owned the neighboring 4 Times Square, sued the city's DOB in July 2022, claiming that the scaffolding around One Times Square would attract crime while worsening congestion on the sidewalk.[194] The renovated tower topped out on December 7, 2023.[195][196]

Architecture

[edit]Eidlitz & McKenzie had originally designed One Times Square in the neo-Gothic style.[197][198] This style was reportedly used because the irregular shape of the site prevented the architects from designing a neoclassical or neo-Renaissance building.[6][8] The Times had described the edifice as being 476 feet (145 m) tall, measured from the deepest basement level to the pinnacle of the tower's flagpole.[199][198] The actual height from street level to roofline was 362 feet 8.75 inches (111 m), making it the city's second tallest office building when it opened, after the Park Row Building.[198][200] Without its tower, the Times Building only measured 228 feet (69 m) tall.[201] David W. Dunlap of the Times wrote that, when the building was completed, it was in his employer's "self-interest to assert that building heights ought to be measured from the lowest level."[200]

Facade

[edit]

When the Times Tower opened, it contained an elaborately decorated facade of limestone and terracotta. The facade's articulation consisted of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a base, shaft, and capital.[6][197] The facade contained several slightly projecting sections, which indicated the locations of steel columns in the building's superstructure.[6][202] The southern portion of the building extended about 60 feet (18 m) back from 42nd Street and was taller than the northern portion.[6][7] This increased the amount of rentable space, since the southern part of the site was wider.[6][8] The plate glass used in the building weighed 28 short tons (25 long tons; 25 t).[203]

The first three stories were elaborately decorated and were clad entirely in cream-colored Indiana limestone, a material chosen for its durability. There were elaborately carved doorways on both Broadway and Seventh Avenue, as well as a horizontal band course of limestone above the third story.[197] Some of the decoration on the lower levels was made of iron, including the ground-floor windows.[204] The windows at the base were smaller than they normally would have been, thereby giving the impression of massiveness.[6][8] The 4th through 12th stories, comprising the shaft, contained little decoration.[25] These stories were clad in cream-colored brick, which was glazed to resemble the terracotta on the rest of the facade.[197] The upper stories contained extremely ornate terracotta details such as brackets and cornices.[197][204] There were ornamental ironwork window frames above the 12th story.[204][205]

Above the 16th story, the roof of the northern section was made of wire glass.[203] The trapezoidal "tower" above the southern half of the building was designed to resemble a square campanile. Each elevation of this tower contained one arched window flanked by smaller, single windows.[202] Critics compared the tower's detail to that of Giotto's Campanile in Florence.[84][206] Arthur G. Bein of American Architect magazine said: "The architect has been free to reproduce almost exactly Giotto's great machicolated cornice with perforated parapet above."[206] Each corner of the tower contained projecting piers, designed in a manner that resembled turrets.[206] Originally, Eidlitz had planned to build a dome atop the southern part of the building, but he scrapped these plans because of the difficulty in placing a circular dome above an irregular trapezoidal massing.[207]

In 1965, the building's original facade was replaced with 420 concrete and marble panels. Each panel was made of a 5-inch-thick (13 cm) layer of precast concrete covered with a 7⁄8-inch-thick (2.2 cm) layer of white Vermont marble. Twenty of these panels measured 9 by 18 feet (2.7 by 5.5 m) and the other 400 panels measured 9 by 12 feet (2.7 by 3.7 m). The rear of each panel was anchored to the building's superstructure.[208] Progressive Architecture magazine criticized the renovation as "a face-lifting job of thorough-going blandness".[78][80] All four elevations of the facade were covered with billboards in the 1990s.[149] From 2022 to 2024, the concrete-and-marble facade of the western, southern, and eastern elevations was removed and replaced with glass panels.[193] In addition, a cantilevered observation deck was installed outside the building.[209]

Structural features

[edit]Substructure

[edit]The foundation of the building extended 60 feet (18 m) deep and was excavated to the underlying layer of bedrock. It is surrounded by waterproof retaining walls, which are backfilled with a mixture of loose stone and cement.[210] The foundation itself consists of cast-steel footings, above which rise the building's steel columns. The footings each measure 5 by 5 feet (1.5 by 1.5 m) across, and their centers are spaced 17 feet (5.2 m) apart. Each steel footing is placed atop a heavy granite block measuring 8 by 8 feet (2.4 by 2.4 m) across and 2 feet (0.61 m) thick, which in turn rests directly on the underlying bedrock.[211][212] Structural loads from the upper stories are carried down into the footings and then spread across the layer of bedrock, which carries a load of 20 short tons per square foot (280 psi; 1,900 kPa).[24] The retaining walls of the foundation are made of red brick.[203] On the eastern part of the site (where the underlying rock sloped upward), workers built a retaining wall with embedded I-beams, providing additional wind bracing.[212]

The building contains three basement levels, the lowest of which is 55 feet (17 m) deep. The Times Square subway station encroaches on a portion of the first and second basement levels.[211][213] The subway station itself is placed 22 feet (6.7 m) below ground and has a ceiling 10 feet (3.0 m) high.[214] The pillars of the subway tunnel were covered in brick[203] and were placed atop sound-dampening sand cushions, minimizing vibrations caused by passing subway trains.[210][215][212] Part of the superstructure is cantilevered above the subway tunnel, since the city's Rapid Transit Commission forbade any obstructions in subway tunnel's right-of-way.[212][216] The northern wall rests on a 30-short-ton (27-long-ton; 27 t) plate girder above the subway tunnel; at the time of construction, it was the heaviest girder in the world to be installed in an office building.[204][215][217][c] This girder measures 60 feet (18 m) long[218] and consists of a group of three I-beams, which collectively measure 3 feet (0.91 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) high.[204] Seven piers in the basement, each measuring 43 feet (13 m) high, carry the entire structural load of the upper levels;[218] they are encased in Portland cement.[211]

Superstructure

[edit]The superstructure contains two-story-tall sections of steel columns. At each story, the columns are connected horizontally by a grid of steel girders.[219] On average, each girder measures 25 feet (7.6 m) long, and there are about 150 pieces of steel used on each story.[24] The seven main structural columns are embedded within the walls on each story.[219] Structural engineers Purdy and Henderson designed three systems of wind bracing for the building.[212][220] The first system consists of the girders on each story, which are welded to the building's columns via gusset plates.[215][220] The building also contains X-shaped diagonal bracing, placed within the partitions next to each of the elevator shafts. Between the individual elevator shafts is a system of knee bracing; it consists of diagonal steel bars shaped like a rotated "K", which extend downward from the centers of the horizontal girders.[220] The structural steel frame carried a dead load of 46 pounds per square foot (2.2 kPa).[204]

Originally, the spaces between the girders were spanned by flat arches made of hollow bricks, which were then covered with a layer of cement. Fireproof timber sleepers were then installed atop these flat arches, and a layer of fireproof wood was installed above these sleepers. The finished wooden floor was then installed above the layer of fireproof wood.[219] The partition walls were constructed of square bricks, which were then finished in plaster. The building's elevator shafts were surrounded by walls made of fire-clay, which were then covered with a layer of tiled brick.[219] The superstructure used 82.923 million pounds (41,000 ST; 37,000 LT; 38,000 t) of iron, brick, mortar, terracotta, limestone, masonry, and other materials.[204][217]

Interior

[edit]

Initially, the entrance on Broadway led to an elevator lobby with decorative pilasters, while the entrance on Seventh Avenue led to an ornamental staircase. The lobby contained a ceiling measuring 15.5 feet (4.7 m) high. The lowest part of the wall contained a marble wainscoting that measured 8 feet (2.4 m) high, while the upper portion of the wall was painted white. The top of the main hall contained a paneled cornice decorated with a shell motif. The floor was made of white mosaic.[221] There were seven oak-framed revolving doors in the building: two at the Broadway entrance to the lobby, one at the 42nd Street entrance, and four leading to the subway station in the basement.[205]

On the first basement level was a pedestrian arcade with several small stores, which ran from street level to the Times Square station's southbound platform.[222] The arcade was closed in 1967 due to high crime,[223] but an archway leading from the station to One Times Square's basement remained visible until the 2000s.[224] The rest of the first basement contained storefronts and the Times's mailing department, while the second basement contained the mailing and repair departments.[211] The third basement is larger than the other basement levels, extending underneath the sidewalk to the curb line on all sides.[210] It covers an area of 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2), three times as large as each of the office stories above.[225] The third basement level contained the pressroom, which was connected via a freight elevator to the second basement.[211] The southern section of the pressroom originally contained four printing presses.[210] The pressroom was illuminated by areaways on 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue, which measured 30 feet (9.1 m) deep and contained glazed-brick cladding.[210] These areaways, as well as the southbound platform of the Times Square station, were covered by glass skylights.[226]

The first twelve stories above ground were rented out to other tenants, except for the New York Times publication office at ground level.[221][227] The 13th through 21st stories contained various departments for The New York Times.[228] Each office was decorated with ornamental cornices and red-oak doors.[221] Offices occupied the northernmost 60 feet (18 m) of the building, which was extremely narrow. In the southern half of the building, a hallway ran down the middle of each story, separating offices to the west and east.[229] These hallways were decorated with white mosaic tile floors and marble wainscoting on the walls.[205] The 16th story, used as a composing room, was the highest story in the northern section of the building. The top six stories, which contained the Times's editorial offices, had windows on all four sides.[229] All offices were located within 23 feet (7.0 m) of a window, and the building was narrow enough that there were no light shafts to provide natural light to interior offices.[202][215] When the building was completed, each office was illuminated by natural light for at least five hours every day.[203]

The former electrical room in the tower's basement serves as a "vault" for the storage of items relating to New Year's Eve celebrations at Times Square, including the ball itself (prior to 2009, when it was replaced with a weatherproofed version that is displayed atop the tower year-round), spare parts, numeral signage and other memorabilia.[230] A room near the top of the tower likewise contains the ball's electronics, including its lighting controller and winch.[231][232]

Mechanical features

[edit]Stairs and elevators were placed on the western side of the building,[229] and there were restrooms on each story next to the stairs and elevators.[233] When the building was constructed, it had seven elevators and over a hundred other motorized appliances, including printing presses, pumps, and fans.[234][235] Of these, five elevators were for passengers and two were for freight.[236] Two of the building's elevators (one passenger and one freight) ran from the basement to the top story, while the other elevators only ran to the 16th story.[237] Although all the passenger elevators could travel at 500 feet per minute (150 m/min), one of these elevators could also be used to transport heavy equipment and could be slowed down to 25 feet per minute (7.6 m/min), thereby doubling its carrying capacity.[236] The elevator cabs were originally copper cages with mirrors on each wall.[238]

The building contained two boilers, which were each capable of 200 horsepower (150 kW). Steam risers distributed heat from the boilers to 542 radiators.[203] Water from the New York City water supply system was drawn into the basement and filtered at a rate of 250 US gallons (950 L) per minute. The filtered water was then pumped up to the 23rd floor and distributed to other stories.[226] In case of a fire, there was a 10,000-US-gallon (38,000 L) water tank in the basement and two 3,000-US-gallon (11,000 L) tanks on the 23rd floor.[239] Three sewage pumps, with a combined capacity of 600 US gallons (2,300 L), were used to pump wastewater out of the building.[205] In addition, there was a gas pipe extending from the cellar to the 16th floor.[226]

Outdoor air was drawn into an air-intake opening at street level and through air filters in the basement; the filtered air was then distributed to the offices. On the Seventh Avenue side of the building was a 389-foot-tall (119 m) ventilation pipe, which faced the building's outer wall and was surrounded by the stairs, elevators, and restrooms on each floor. During the summer, a large electric fan pushed stale air upward through the ventilation pipe.[233] The building also contained 2,400 electrical outlets and over 6,200 lamps.[203][204] The offices were illuminated by 150 ornate chandeliers on the 2nd through 14th floors.[226] There originally were 74 miles (119 km) of electrical wires and 21 miles (34 km) of electrical conduits in the building.[204][217]

Billboards

[edit]One Times Square's first electronic billboards were installed in 1996.[149] Filings related to the building's 1997 sale revealed that the billboards on the tower had been generating a net revenue of $7 million yearly,[139] representing a 300% profit.[240] Sherwood Equities president Brian Turner estimated in 2005 that over 200 million people saw the Times Square Ball drop at the building every year.[241] With growing tourism and high traffic in the Times Square area (with a yearly average of over 100 million pedestrians—alongside its prominence in media coverage of New Year's festivities, seen by a wide audience yearly), annual revenue from the signs grew to over $23 million by the year 2012—rivaling London's Piccadilly Circus as the most valuable public advertising space in the world.[242][243]

Front billboard and displays

[edit]A Cup Noodles billboard was added to the front facade of the tower in early 1996,[244] later accompanied by an animated Budweiser sign.[245] The Cup Noodles billboard, operated by Nissin Foods, emitted steam (an effect that had also been used by other Times Square billboards, such as the Camel Cigarettes sign).[149] The Cup Noodles billboard was replaced in 2006 by a General Motors billboard featuring a Chevrolet branded clock. Due to cutbacks resulting from GM's bankruptcy and re-organization, the Chevrolet Clock was removed in 2009[246] and eventually replaced by a Kia Motors advertisement billboard.[247] This billboard was itself replaced in 2010 by a Dunkin' Donuts display.[248][249]

At the base of the tower, a Panasonic display operated by NBC known as Astrovision was introduced as a replacement for Sony's Jumbotron in December 1996.[250][34] News Corporation (later renamed 21st Century Fox) replaced NBC as the operator and sponsor of the Astrovision screen in 2006.[251] Sony returned to One Times Square in 2010, replacing the News Corp. Panasonic screen with a new high-definition LED display.[252]

In 2019, the individual billboard screens on the front of the tower were replaced by one 350-foot-tall (110 m) Samsung LED display, with a resolution of 1312×7380 pixels. The installation of the display necessitated the removal of the Zipper.[185][186][187] The display measures about 25 stories high and consists of four connected screens.[253] When the building's 2020s renovation is complete, the structure is planned to have additional electronic displays.[254]

Topmost screen

[edit]

A 55-foot-tall (17 m) video screen sponsored by ITT Corporation was introduced to the top of the tower, which would feature video advertisements and community service announcements.[149][255] In 1998, Discover Card replaced ITT Corporation as the operator and sponsor of the topmost screen on One Times Square as part of a ten-year deal. The deal came alongside the announcement that Discover Card would be an official sponsor of Times Square's 1999–2000 festivities.[256]

In December 2007, Toshiba took over sponsorship of the top-most screen of One Times Square from Discover Card in a 10-year lease.[257] During its sponsorship, the display featured advertising for Toshiba products, as well as advertising promoting Japanese tourism.[258] Upgrades to the upper portion of One Times Square commenced in 2008, including the installation of new Toshiba high-definition LED displays (known as ToshibaVision), and the redesign of its roof to accommodate a larger New Year's Eve ball, which became a year-round fixture of the building beginning in 2009.[230][259] Toshiba announced that it would end its One Times Square sponsorship in early 2018, citing ongoing cost-cutting measures.[258][260][261]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This was one of four northward-facing plots south of 59th Street that were formed by the convergence of Broadway, another avenue, and a crosstown street. The Flatiron Building was built on the triangular plot south of Madison Square, at 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue. A park was built on the plot south of Herald Square, at 34th Street and Sixth Avenue. The curved site south of Columbus Circle, at 59th Street and Eighth Avenue, is now occupied by 2 Columbus Circle.[8]

- ^ Now 3 Times Square, 4 Times Square, 5 Times Square, and Times Square Tower

- ^ Larger girders were used above the Colonial Theatre in Boston.[218]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "One Times Square". CTBUH Skyscraper Database. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2016. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

- ^ "Allied Chemical Building". CTBUH Skyscraper Database. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2016. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016.

- ^ "1 Times Square". Emporis. 2016. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c "1475 Broadway, 10036". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ a b White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landau & Condit 1996, p. 312.

- ^ a b "A New Building for the New York Times; Plans for a Monumental Structure on Long Acre Square. The Architectural and Other Features of the Building Which Is Being Erected at the New Centre of Travel and Activity on Manhattan Island". The New York Times. June 27, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e New York Times Building Supplement 1905, p. BS7.

- ^ a b "Allied Chemical Wins Times Square Address". The New York Times. September 7, 1966. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (July 15, 1990). "Addresses in Times Square Signal Prestige, if Not Logic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Times Sq-42 St (S)". mta.info. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "New Subway Company Buys Broadway Site; The Deal May Foreshadow Station Changes at 42d Street". The New York Times. April 25, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "A New Home for the New York Times; The Newspaper to Move Up Town Early in 1904. It Is to Have a Modern Steel-Construction Building on the Triangle at Broadway, Seventh Avenue and West 42d Street". The New York Times. August 4, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "Found Place Where Young Bought Trunk; Dealer and His Son Say Purchaser Was Clean Shaven". The New York Times. September 25, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Talese, Gay (August 24, 1963). "Times Square Loses Name That Abided 60 Years; Immortalization in Granite Proves All Too Mortal Refacing of Times Tower to Remove Thorley 'Plaques' A Budding Career Lease at $4,000 a Year". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Douglas Leigh New Owner: 'Times' Sells Times Tower; Exhibition Hall Is Planned". New York Herald Tribune. March 16, 1961. p. 1. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1326871256.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (March 17, 1999). "Former Times Building Is Named a Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ (Former) New York Times Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 16, 1999. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c New York Times Building (originally the Times Annex) (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 24, 2001. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Leases—Borough of Manhattan". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 70, no. 1795. August 9, 1902. p. 209. Archived from the original on August 6, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Hood, Clifton (1978). "The Impact of the IRT in New York City" (PDF). Historic American Engineering Record. p. 182. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 17, 2021. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b "New Home for "The Times": It Announces Plans for Its Uptown Building". New-York Tribune. August 4, 1902. p. 7. ProQuest 571264569.

- ^ a b c New York Times Building Supplement 1905, p. BS18.

- ^ a b c "Enormous Weight of Modern Structures; Uneven Pressures to Contend With in the New Times Building. Skeleton Frame Going Up at the Rate of About Three Stories a Week – How All the Steel Is Tested". The New York Times. November 29, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ a b "New Times Building Cornerstone Laid; Bishop Henry C. Potter Invokes Blessings on the Structure". The New York Times. January 19, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Bishop Potter at the Ceremony: Offers Prayer at Laying of Cornerstone of New Times Building". New-York Tribune. January 19, 1904. p. 6. ProQuest 571528689.

- ^ "To Be Called Times Square; Aldermen Vote to Rename Long Acre Square, Site of New Times Building". The New York Times. April 6, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "Stop Building Work: Seventeen Unions Represented in New York Strike". The Washington Post. August 2, 1904. p. 5. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 144508368.

- ^ "Big Strike in New York: Work Stopped on a Number of Important Buildings". The Hartford Courant. August 2, 1904. p. 1. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 555246037.

- ^ New York Times Building Supplement 1905, pp. BS18–BS19.

- ^ "Election Results by Times Building Flash; Steady Light Westward – Roosevelt; Eastward – Parker". The New York Times. November 6, 1904. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "To-day's Times Issued From Its New Home; Delicate Task of Removal Was Well Completed". The New York Times. January 2, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ Brainerd, Gordon (2006). Bell Bottom Boys. Infinity Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9780741433992. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Crump, William D. (2014). Encyclopedia of New Year's Holidays Worldwide. McFarland. p. 242. ISBN 9781476607481. Archived from the original on June 19, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Boxer, Sarah B. (December 31, 2007). "NYC ball drop goes 'green' on 100th anniversary". CNN. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014.

- ^ "Great Drug Store to Be in the Times Building; Hegeman & Co. to Have One of the Largest in the World". The New York Times. July 31, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "News Will Be Plashed from the Tower of The Times Building on Tuesday Night". The New York Times. November 5, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Music by Wireless to the Times Tower; Telephone Messages Also Received Through the Ether". The New York Times. March 8, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c McKendry, Joe (2011). One Times Square: A Century of Change at the Crossroads of the World. David R. Godine Publisher. pp. 10–14. ISBN 9781567923643. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Lankevich, George J. (2001). Postcards from Times Square. Square One Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 9780757001000. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Nash, Eric P. (December 30, 2001). "F.Y.I." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "What's Your Problem?". Newsday. December 30, 1965. p. 48. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watch the Times Tower; The Descent of an Electric Ball Will Mark the Arrival of 1908 To-night". The New York Times. December 31, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Gets Porto Rico Message; New Wireless Receiver Intercepts Dispatch After Other Stations Failed to Take It". The New York Times. January 18, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "The Times to Flash Election Results; North Means "Taft," South "Bryan," West "Hughes," and East "Chanler"". The New York Times. November 2, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ^ "Loti Amazed by Times Tower View; Tells in His Impressions of New York How the City Frightened and Fascinated Him". The New York Times. February 23, 1913. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "New York's Marvels Awe Sultan of Sulu; Kiram II. and His Suite Greatly Impressed by the View of the City from The Times Tower". The New York Times. September 25, 1910. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "A Times Annex Near Times Square; Building 143 by 100 Is to be Constructed to Meet This Paper's Needs". The New York Times. March 29, 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ The Times Annex: A Wonderful Workshop. The New York Times Company. 1913. p. 27.

- ^ "The "New York Times"". The Hartford Courant. February 4, 1913. p. 8. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 555973270.

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (November 20, 2007). "Pride and Nostalgia Mix in The Times's New Home". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ "History of Times Square". The Telegraph. London. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- ^ a b c Long, Tony (November 6, 2008). "Nov. 6, 1928: All the News That's Lit". Wired. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008.

- ^ "The New York Times Company Enters The 21st Century With A New Technologically Advanced And Environmentally Sensitive Headquarter" (PDF) (Press release). The New York Times Company. November 16, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008.

- ^ "Times Tower Fire Still a Mystery; Inspection Turns Up No Clue to Fatal Blaze's Origin". The New York Times. November 25, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Beacon on Times Building; Neon Light, Visible for 50 Miles, Adds to Brilliance of Square". The New York Times. September 1, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Huge Times Sign Will Flash News; Electric Bulletin Board, Used for the Election, Will Be in Nightly Operation". The New York Times. November 8, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "14,800 Bulbs Give News to New York". The Gazette. November 9, 1928. p. 13. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Times' Famous News Sign Will Be 20 Years Old Saturday; Among First Moving Electric Bulletins Was Description of President Hoover's Election – Many Momentous Stories Told". The New York Times. November 2, 1948. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Young, Greg; Meyers, Tom (2016). The Bowery Boys: Adventures in Old New York: An Unconventional Exploration of Manhattan's Historic Neighborhoods, Secret Spots and Colorful Characters. Ulysses Press. p. 289. ISBN 9781612435763. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Poulin, Richard (2012). Graphic Design and Architecture, A 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in the Modern World. Rockport Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 9781592537792. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Times Electric News Sign Goes Dark Under New Dimout, Probably for Duration". The New York Times. May 19, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Election Result Signals Of Times Banned by War". The New York Times. November 1, 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Walker, Danton (October 22, 1943). "Broadway". New York Daily News. p. 129. ISSN 2692-1251. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times to Stop News Sign Today as 'Brownout' Aid". The New York Times. November 1, 1943. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Watson, John (November 2, 1943). "Broadway Coyly Tests Brilliance As Dimout Ends: Some Theaters Blaze Forth, but Patches of Gloom Cloud First-Night Glory When the Lights Went On Again All Over New York". New York Herald Tribune. p. 38. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1284445041.

- ^ a b c d Gelder, Lawrence Van (December 11, 1994). "Lights Out for Times Square News Sign?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 8, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "The Times Electric Sign Attraction for Many Eyes". The New York Times. August 15, 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Times Sq. Getting Vote Result Sign; 85-Foot Electric Indicator on Times Tower Will Give Returns at a Glance". The New York Times. October 24, 1952. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ "Times' Lighted 'Thermometer' Will Give the Election Returns". The New York Times. November 4, 1956. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 2, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans (November 22, 1957). "Landmark Signs Dedicated Here; 20 Are first of Many That Will Mark Historical and Architectural Sites". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Sold for Exhibit Hall; Douglas Leigh Buys 24-Story Building in the Square". The New York Times. March 16, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Building In Times Square Sold To Allied Chemical: Firm Will Remodel Facility But Maintain the Traditions Of New York City Landmark". Wall Street Journal. April 17, 1963. p. 5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 132873722.

- ^ "Third Body Found in Times Sq. Fire; Porter as Well as 2 Firemen Died in Times Tower Blaze". The New York Times. November 24, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Fire is Laid to Smoking; Cavanagh Says Blaze Began in Storeroom for Toys". The New York Times. December 19, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Headlines Again Circle Former Times Tower". The New York Times. March 9, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Ennis, Thomas W. (April 17, 1963). "Old Times Tower to Get New Face; 26-Story Building Will Be Stripped and Recovered in Glass and Marble". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 21, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "A la Recherche du TIMES Perdu" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 44. May 1963. p. 82. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Benjamin Bailyn Is Dead at 55; Architect of the Allied Tower". The New York Times. July 23, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. New York: Monacelli Press. p. 1103. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240. OL 1130718M.

- ^ "Modernization Project Begins on Times Tower". The New York Times. October 29, 1963. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Times Tower Due New Face: Structure Being Built on Original Framework". The Sun. February 24, 1964. p. 6. ProQuest 540133645.

- ^ "Times Tower Box of 1904 Unsealed". The New York Times. March 18, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Huxtable, Ada Louise (March 20, 1964). "Architecture: That Midtown Tower Standing Naked in the Wind: Skyscraper Buffs See Antique Skeleton Fancy Steel Framing Elaborated by Rivets". The New York Times. p. 30. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 115725139.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (January 31, 1965). "Marble-Clad Buildings Brighten Midtown Manhattan". The New York Times. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 116760160.

- ^ "Allied Tower Makes False Start on Facade". The New York Times. August 4, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (November 28, 2014). "A Home for the Headlines". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Electronic News Bulletins To Return to Times Square". Wall Street Journal. January 20, 1986. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398033841.

- ^ "Highest Electric Signs In Times Sq. Go On Today". The New York Times. July 23, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Buckley, Thomas (December 3, 1965). "Allied's Times Square Tower Dedicated by Gov. Rockefeller; Allied's Times Square Tower Dedicated by Gov. Rockefeller". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Old N.Y. Times Tower keeps up tradition". The Christian Science Monitor. December 17, 1965. p. 11. ISSN 0882-7729. ProQuest 510762391.

- ^ Lippa, Si (July 27, 1966). "Focus…: Allied Chemical: Tower of Strength: Do Additional Fabrics Loom In Allied Chemical's Future?". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 113, no. 18. pp. 1, 45. ProQuest 1523514401.

- ^ "Allied Chemical Tower To Get an English Cafe". The New York Times. April 12, 1965. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Claiborne, Craig (August 22, 1966). "Dining in a Modern Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ "Fashion Rtw: Allied Tower Reported For Sale". Women's Wear Daily. Vol. 125, no. 56. September 21, 1972. p. 19. ProQuest 1523642418.

- ^ a b c Stetson, Damon (October 10, 1972). "'For Sale' Sign Is Posted At Allied Chemical Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Developer Rents Allieds' Tower In Times Square". The Hartford Courant. November 1, 1973. p. 55. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 551980429.

- ^ Tomasson, Robert E. (October 31, 1973). "Lessee Will Put Exhibits In Times Square Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Tomasson, Robert E. (November 18, 1973). "An Innovator Goes to Work in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "Times Tower Sign To Get Good News". The Washington Post. April 2, 1974. p. A14. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 146202415.

- ^ a b c d Kaiser, Charles (May 15, 1975). "A Glittery Times Sq. Tower Due". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Randall, Gabrielan (2000). Times Square and 42nd Street in Vintage Postcards. Arcadia Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 9780738504285. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bloom, Ken (2013). Broadway: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 530. ISBN 9781135950194. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Josephs, Lawrence (January 3, 1982). "A New Owner Takes the Reins in Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b "A Prismatic Tower". The Washington Post. May 15, 1975. p. D2. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 146376858.

- ^ "Mirrors Will Sheathe Times Square Tower". The New York Times. May 15, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Asbury, Edith Evans (March 3, 1976). "Mayor and Mouse Open One Times Square". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Doughtery, Philip H. (October 11, 1976). "Advertising: An Addition to Times Square". The New York Times. p. 5. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 122847653.

- ^ a b Sagalyn, Lynne B. (2003). Times Square Roulette: Remaking the City Icon. MIT Press. p. 323. ISBN 9780262692953. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Horsley, Carter B. (November 15, 1979). "Razing of One Skyscraper to Build 3 New Ones Proposed in Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 681.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (February 27, 1981). "Latest Times Sq. Proposal: Why It May Succeed: An Appraisal Renovation of Times Tower Proposed". The New York Times. p. B4. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 121804824.

- ^ Horsley, Carter B. (July 1, 1981). "42d St. Plan Would Add Towers, Theaters and 'Bright Lights': Plans for 42d St. Would Add Theaters and 'Bright Lights'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 684.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (December 21, 1983). "4 New Towers for Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb, Martin (November 29, 1983). "Developer Seeks to Tear Down Times Sq. Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Spiegelman, Arthur (January 5, 1984). "Time's running out for this landmark". South China Morning Post. p. 15. ProQuest 1553940873.

- ^ Depalma, Anthony (July 11, 1984). "About Real Estate; One Times Square, Its Future Unsure, is Sold Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Bird, David (June 15, 1984). "New York Day by Day". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (December 18, 1984). "New York Day by Day; Objections on Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Gottlieb, Martin (March 3, 1985). "Civic Groups Assail Makeup Of Times Tower Committee". The New York Times. p. 34. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 111225579.

- ^ a b c Grant, Peter (May 3, 1993). "Ball could drop on One Times Sq. lender". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 9, no. 18. p. 4. ProQuest 219173143.

- ^ "Sign of the Times for NY Newsday". Newsday. January 17, 1986. p. 6. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Shawn G. (March 12, 1986). "Real Estate; Times Sq. Tower's Renewal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (August 15, 1986). "An Appraisal; Times Sq. Bell Tower: the Wrong Centerpiece". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (July 2, 1988). "Reprieve for a Famed Tower on Times Sq". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Robbins, Jim (June 8, 1988). "Pictures: New State-Of-The-Art Facilities For No. 1 Times Square Structure". Variety. Vol. 331, no. 7. p. 7. ISSN 0042-2738. ProQuest 1438491962.

- ^ McCain, Mark (April 9, 1989). "Commercial Property: Times Sq. Signage; A Mandated Comeback for the Great White". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Wax, Alan J. (March 14, 1992). "1 Times Square in Bankruptcy". Newsday. p. 15. ISSN 2574-5298. Archived from the original on September 4, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "Sony to Polish Image with Video Display for Times Square". Wall Street Journal. October 12, 1990. p. B4B. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398189556.

- ^ Ramirez, Anthony (October 11, 1990). "The Media Business: Advertising – Addenda; Sony to Help Make Times Square Brighter". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Howe, Marvine (March 13, 1994). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; For Times Square Couch Potatoes . . ". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Ravo, Nick (March 14, 1992). "Times Square Landmark Files in Bankruptcy". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- ^ Grant, Peter (June 7, 1993). "N.Y., feds make foreclosure less taxing". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 9, no. 23. p. 13. ProQuest 219143472.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (December 30, 1994). "Times Sq. Flash: ***ZIPPER SAVED***". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ "Pearson will keep 'zipper' running at Times Square". Wall Street Journal. December 30, 1994. p. C6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398558205.

- ^ Lambert, Bruce (January 8, 1995). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; The 'Zipper' Is Speaking a New Language". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ "Bank Buys Building Where the Ball Drops". The New York Times. January 26, 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Bagli, Charles V. (June 19, 1997). "Tower in Times Sq., Billboards and All, Earns 400% Profit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ a b "Wrangle kills plan for US Madame Tussaud's". South China Morning Post. March 29, 1995. p. 65. ProQuest 1535995762.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (March 23, 1995). "Madame Tussaud's Loses Bidding War and Drops Times Sq. Plan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ Levi, Vicki Gold; Heller, Steven (2004). Times Square Style: Graphics from the Great White Way. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781568984902. Archived from the original on August 5, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ Brill, Louis M. "Signage in the crossroads of the world". SignIndustry. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Holusha, John. "Times Square Signs: For the Great White Way, More Glitz". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Dow Jones taking over news 'zipper'". Portsmouth Daily Times. Associated Press. June 10, 1995. p. B8. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Dow Jones will operate Times Square 'zipper' sign". Wall Street Journal. June 9, 1995. p. A5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398448932.

- ^ Chen, David W. (May 6, 1997). "Times Sq. Sign Turns Corner Into Silence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 9, 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Lueck, Thomas J. (May 17, 1996). "Less Glitter on Times Square: No More Jumbotron". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved August 9, 2022.