Direct Action Day

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (September 2024) |

| Direct Action Day 1946 Calcutta Riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Partition of India | |||

| |||

| Date | 16 August 1946 | ||

| Location | 22°35′N 88°22′E / 22.58°N 88.36°E | ||

| Caused by | Perceived unfairness and discrimination, misinformation | ||

| Goals | Partition of India | ||

| Methods | General strike, rioting, assaults and arson | ||

| Resulted in | Partition of Bengal | ||

| Parties | |||

| Lead figures | |||

No centralized leadership, though local Indian National Congress leaders took part Local chapter of All-India Muslim League | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 4,000 - 10,000 (Hindus & Muslims) [3][4] | ||

| Part of a series on |

| Persecution of Hindus in pre-1947 India |

|---|

| Issues |

| Incidents |

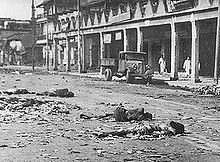

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946) was the day the All-India Muslim League decided to take a "direct action" using general strikes and economic shut down to demand a separate Muslim homeland after the British exit from India. Also known as the 1946 Calcutta Riots, it soon became a day of communal violence in Calcutta.[5] It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) in the Bengal province of British India.[3] The day also marked the start of what is known as The Week of the Long Knives.[6][7] While there is a certain degree of consensus on the magnitude of the killings (although no precise casualty figures are available), including their short-term consequences, controversy remains regarding the exact sequence of events, the various actors' responsibility and the long-term political consequences.[8]

There is still extensive controversy regarding the respective responsibilities of the two main communities, the Hindus and the Muslims, in addition to individual leaders' roles in the carnage. The dominant British view tends to blame both communities equally and to single out the calculations of the leaders and the savagery of the followers, amongst whom there were criminal elements.[citation needed] In the Indian National Congress' version of the events, the blame tends to be laid squarely on the Muslim League and in particular on the Chief Minister of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy.[9] The Muslim League alleged that the Congress Party and the Hindus used the opportunity offered by the general strikes of the Direct Action Day to teach the Muslims in Calcutta a lesson and to kill them in great numbers.[citation needed] Thus, the riots opened the way to a partition of Bengal between a Hindu-dominated Western Bengal including Calcutta and a Muslim-dominated Eastern Bengal (now Bangladesh).[8]

The All-India Muslim League and the Indian National Congress were the two largest political parties in the Constituent Assembly of India in the 1940s. The Muslim League had demanded since its 1940 Lahore Resolution for the Muslim-majority areas of India in the northwest and the east to be constituted as 'independent states'. The 1946 Cabinet Mission to India for planning of the transfer of power from the British Raj to the Indian leadership proposed a three-tier structure: a centre, groups of provinces and provinces. The "groups of provinces" were meant to accommodate the Muslim League's demand. Both the Muslim League and the Congress in principle accepted the Cabinet Mission's plan.[10] However; Nehru's speech on 10 July 1946 rejected the idea that the provinces would be obliged to join a group[11] and stated that the Congress was neither bound nor committed to the plan.[12] In effect, Nehru's speech squashed the mission's plan and the chance to keep India united.[11] Jinnah interpreted the speech as another instance of treachery by the Congress.[13] With Nehru's speech on groupings, the Muslim League rescinded its previous approval of the plan[14] on 29 July.[15]

Consequently, in July 1946, the Muslim League withdrew its agreement to the plan and announced a general strike (hartal) on 16 August, terming it Direct Action Day, to assert its demand for a separate homeland for Muslims in certain northwestern and eastern provinces in colonial India.[16][17] Calling for Direct Action Day, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the All India Muslim League, said that he saw only two possibilities "either a divided India or a destroyed India".[18][19]

Against a backdrop of communal tension, the protest triggered massive riots in Calcutta.[20][21] More than 4,000 people died and 100,000 residents were left homeless in Calcutta within 72 hours.[3][4] The violence sparked off further religious riots in the surrounding regions of Noakhali, Bihar, United Provinces (modern day Uttar Pradesh), Punjab (including massacres in Rawalpindi) and the North Western Frontier Province.[22] The events sowed the seeds for the eventual Partition of India.

Background

[edit]In 1946, the Indian independence movement against the British Raj had reached a pivotal stage. British Prime Minister Clement Attlee sent a three-member Cabinet Mission to India aimed at discussing and finalizing plans for the transfer of power from the British Raj to the Indian leadership.[23] After holding talks with the representatives of the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League—the two largest political parties in the Constituent Assembly of India—on 16 May 1946, the Mission proposed a plan of composition of the new Dominion of India and its government.[20][24] The Muslim League demand for 'autonomous and sovereign' states in the northwest and the east was accommodated by creating a new tier of 'groups of provinces' between the provincial layer and the central government. The central government was expected to handle the subjects of defence, external affairs and communications. All other powers would be relegated to the 'groups'.[25]

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the one-time Congressman and now the leader of the Muslim League, had accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan of 16 June, as had the central presidium of the Congress.[20][26] On 10 July, however, Jawaharlal Nehru, the Congress President, held a press conference in Bombay declaring that although the Congress had agreed to participate in the Constituent Assembly, it reserved the right to modify the Cabinet Mission Plan as it saw fit.[26] Fearing Hindu domination in the central government, the Muslim League politicians pressed Jinnah to revert to "his earlier unbending stance".[27] Jinnah rejected the British Cabinet Mission plan for transfer of power to an interim government which would combine both the Muslim League and the Indian National Congress, and decided to boycott the Constituent Assembly. In July 1946, Jinnah held a press conference at his home in Bombay. He proclaimed that the Muslim League was "preparing to launch a struggle" and that they "have chalked out a plan".[17] He said that if the Muslims were not granted a separate Pakistan then they would launch "direct action". When asked to be specific, Jinnah retorted: "Go to the Congress and ask them their plans. When they take you into their confidence I will take you into mine. Why do you expect me alone to sit with folded hands? I also am going to make trouble."[17]

The next day, Jinnah announced 16 August 1946 would be "Direct Action Day" and warned Congress, "We do not want war. If you want war we accept your offer unhesitatingly. We will either have a divided India or a destroyed India."[17] The Muslim League had thus said “goodbye to Constitutional methods” and was ready to “create trouble”.[28]

In his book The Great Divide, H V Hodson recounted, "The Working Committee followed up by calling on Muslims throughout India to observe 16th August as 'Direct Action Day'. On that day, meetings would be held all over the country to explain the League's resolution. These meetings and processions passed off—as was manifestly the central League leaders' intention—without more than commonplace and limited disturbances, with one vast and tragic exception ... What happened was more than anyone could have foreseen."[29]

In Muslim Societies: Historical and Comparative Aspects, edited by Sato Tsugitaka, Nakazato Nariaki writes:

From the viewpoint of institutional politics, the Calcutta disturbances possessed a distinguishing feature in that they broke out in a transitional period which was marked by the power vacuum and systemic breakdown. It is also important to note that they constituted part of a political struggle in which the Congress and the Muslim League competed with each other for the initiative in establishing the new nation-state(s), while the British made an all-out attempt to carry out decolonization at the lowest possible political cost for them. The political rivalry among the major nationalist parties in Bengal took a form different from that in New Delhi, mainly because of the broad mass base those organizations enjoyed and the tradition of flexible political dealing in which they excelled. At the initial stage of the riots, the Congress and the Muslim League appeared to be confident that they could draw on this tradition even if a difficult situation arose out of political showdown. Most probably, Direct Action Day in Calcutta was planned to be a large-scale hartal and mass rally (which is an accepted part of political culture in Calcutta) which they knew very well how to control. However, the response from the masses far exceeded any expectations. The political leaders seriously miscalculated the strong emotional response that the word 'nation', as interpreted under the new situation, had evoked. In August 1946 the 'nation' was no longer a mere political slogan. It was rapidly turning into 'reality' both in realpolitik and in people's imaginations. The system to which Bengal political leaders had grown accustomed for decades could not cope with this dynamic change. As we have seen, it quickly and easily broke down on the first day of the disturbances.[16]

Prelude

[edit]Since the 11–14 February 1946 riots in Calcutta, communal tension had been high. Hindu and Muslim newspapers whipped up public sentiment with inflammatory and highly partisan reporting that heightened antagonism between the two communities.[30] Adding further fuel to inflamed Muslim communal sentiments was a pamphlet written by the Mayor of Calcutta, Syed Mohammed Usman, where he said, "We Muslims have had the crown and have ruled. Do not lose hearts, be ready and take swords. Oh kafir! Your doom is not far".[31]

Following Jinnah's declaration of 16 August as the Direct Action Day, acting on the advice of R.L. Walker, the then Chief Secretary of Bengal, the Muslim League Chief Minister of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, requested the Governor of Bengal Sir Frederick Burrows to declare a public holiday on that day. Governor Burrows agreed. Walker made this proposal with the hope that the risk of conflicts, especially those related to picketing, would be minimized if government offices, commercial houses and shops remained closed throughout Calcutta on 16 August.[3][16][32] The Bengal Congress protested against the declaration of a public holiday, arguing that a holiday would enable 'the idle folks' to successfully enforce hartals in areas where the Muslim League leadership was not so powerful. Congress accused the League government of "having indulged in 'communal politics' for a narrow goal".[33] Congress leaders thought that if a public holiday was observed, its own supporters would have no choice but to close down their offices and shops, and thus be compelled against their will to lend a hand in the Muslim League's hartal.[16]

On 14 August, Kiran Shankar Roy, the leader of the Congress Party in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, called on Hindu shopkeepers to not observe the public holiday, and keep their businesses open in defiance of the hartal.[34][16]

The Star of India, an influential local Muslim newspaper, edited by Raghib Ahsan, the Muslim League MLA from Calcutta published the detailed program for the day. The program called for complete a hartal and general strike in all spheres of civic, commercial and industrial life except essential services. The notice proclaimed that processions would start from multiple parts of Calcutta, Howrah, Hooghly, Metiabruz and 24 Parganas, and would converge at the foot of the Ochterlony Monument (now known as Shaheed Minar) where a joint mass rally presided over by Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy would be held. The Muslim League branches were advised to depute three workers in every mosque in every ward to explain the League's action plan before Juma prayers. Moreover, special prayers were arranged in every mosque on Friday after Juma prayers for the freedom of Muslim India.[35] The notice drew divine inspiration from the Quran, emphasizing on the coincidence of Direct Action Day with the holy month of Ramzaan, claiming that the upcoming protests were an allegory of Prophet Muhammad's conflict with heathenism and subsequent conquest of Mecca and establishment of the Kingdom of Heaven in Arabia.[35]

Hindu public opinion was mobilized around the Akhand Hindusthan (United India) slogan.[20] Certain Congress leaders in Bengal imbibed a strong sense of Hindu identity, especially in view of the perceived threat from the possibility of marginalizing themselves into minority against the onslaught of the Pakistan movement. Such mobilization along communal lines was partly successful due to a concerted propaganda campaign which resulted in a 'legitimization of communal solidarities'.[20]

On the other hand, following the protests against the British after INA trials, the British administration decided to give more importance to protests against the government, rather than management of communal violence within the Indian populace, according to their "Emergency Action Scheme".[16] Frederick Burrows, the Governor of Bengal, rationalized the declaration of "public holiday" in his report to Lord Wavell—Suhrawardy put forth a great deal of effort to bring reluctant British officials around to calling the army in from Sealdah Rest Camp. Unfortunately, British officials did not send the army out until 1:45 a.m. on 17 August.[16]

Many of the mischief-makers were people who would have had idle hands anyhow. If shops and markets had been generally open, I believe that there would have been even more looting and murder than there was; the holiday gave the peaceable citizens the chance of staying at home.

— Frederick Burrows, Burrows' Report to Lord Wavell.[3]

Riots and massacre

[edit]

Troubles started on the morning of 16 August. Even before 10 o'clock the Police Headquarters at Lalbazar had reported that there was excitement throughout the city, that shops were being forced to close, and that there were many reports of brawls, stabbing and throwing of stones and brickbats. These were mainly concentrated in the North-central parts of the city like Rajabazar, Kelabagan, College Street, Harrison Road, Colootola and Burrabazar.[3] Several of these areas had also been rocked by communal riots in December 1910.[36] In these areas the Hindus were in a majority and were also in a superior and powerful economic position. The trouble had assumed the communal character which it was to retain throughout.[3]

The meeting began around 2 pm though processions of Muslims from all parts of Calcutta had started assembling since the midday prayers. A large number of the participants were reported to have been armed with iron bars and lathis (bamboo sticks). The numbers attending were estimated by a Central Intelligence Officer's reporter at 30,000 and by a Special Branch Inspector of Calcutta Police at 500,000. The latter figure is impossibly high and the Star of India reporter put it at about 100,000. The main speakers were Khawaja Nazimuddin and Chief Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy. Khwaja Nazimuddin in his speech preached peacefulness and restraint but spoilt the effect and flared up the tensions by stating that till 11 o'clock that morning all the injured persons were Muslims, and the Muslim community had only retaliated in self-defence.[3] Huseyn Suhrawardy, in his speech, appeared to indirectly promise that no action would be taken against armed Muslims.[37]

The Special Branch of Calcutta Police had sent only one shorthand reporter to the meeting, with the result that no transcript of the Chief Minister's speech is available. But the Central Intelligence Officer and a reporter, who Frederick Burrows believed was reliable, deputed by the military authorities agree on one statement (not reported at all by the Calcutta Police). The version in the former's report was—"He [the Chief Minister] had seen to police and military arrangements who would not interfere".[3] The version of the latter's was—"He had been able to restrain the military and the police".[3] However, the police did not receive any specific order to "hold back". So, whatever Suhrawardy may have meant to convey by this, the impression of such a statement on a largely uneducated audience is construed by some to be an open invitation to disorder[3] indeed, many of the listeners are reported to have started attacking Hindus and looting Hindu shops as soon as they left the meeting.[3][38] Subsequently, there were reports of lorries (trucks) that came down Harrison Road in Calcutta, carrying hardline Muslim gangsters armed with brickbats and bottles as weapons and attacking Hindu-owned shops.[39]

A 6 pm curfew was imposed in the parts of the city where there had been rioting. At 8 pm forces were deployed to secure main routes and conduct patrols from those arteries, thereby freeing up police for work in the slums and the other underdeveloped sections.[40]

Syed Abdullah Farooqui, President of Garden Reach Textile Workers' Union, led a radical mob into the compound of Kesoram Cotton Mills in Metiabruz. The death toll of labourers residing in the mills, among whom were a substantial number of Odias, reported to be between 7,000 and 10,000.[41] On 25 August, four survivors lodged a complaint at the Metiabruz police station against Farooqui.[42] Bishwanath Das, a Minister in the Government of Orissa, visited Lichubagan to investigate into the killings of the mill labourers.[43] Many authors claim Hindus were the primary victims.[2]

The worst of the killing took place during the day on 17 August. By late afternoon, soldiers brought the worst areas under control and the military expanded its hold overnight. In the slums and other areas, however, which were still outside military control, lawlessness and rioting escalated hourly. In the morning of 18 August, "Buses and taxis were charging about loaded with Sikhs and Hindus armed with swords, iron bars and firearms."[44]

Skirmishes between the communities continued for almost a week. Finally, on 21 August, Bengal was put under Viceroy's rule. 5 battalions of British troops, supported by 4 battalions of Indians and Gurkhas, were deployed in the city. Lord Wavell alleged that more troops ought to have been called in earlier, and there is no indication that more British troops were not available.[2] The rioting reduced on 22 August.[45]

Characteristics of the riot and demographics in 1946

[edit]Suhrawardy put forth a great deal of effort to bring reluctant British officials around to calling the army in from Sealdah Rest Camp. Unfortunately, British officials did not send the army out until 1:45 a.m. on 17 August.[16] Violence in Calcutta, between 1945 and 1946, passed by stages from Indian versus European to Hindu versus Muslim. Indian Christians and Europeans were generally free from molestation[46] as the tempo of Hindu-Muslim violence quickened. The decline of anti-European feelings as communal Hindu-Muslim tensions increased during this period is evident from the casualty numbers. During the riots of November 1945, casualty of Europeans and Christians were 46; in the riots of the 10–14 February 1946, 35; from 15 February to 15 August, only three; during the Calcutta riots from 15 August 1946 to 17 September 1946, none.[47]

Calcutta had 2,952,142 Hindus, 1,099,562 Muslims, and 12,852 Sikhs in 1946, the year before partition. After independence, the Muslim population came down to 601,817 due to the migration of 500,000 Muslims from Calcutta to East Pakistan after the riot. The 1951 Census of India recorded that 27% of Calcutta's population was East Bengali refugees mainly Hindu Bengalis. Millions of Bengali Hindus from East Pakistan had taken refuge mainly in the city and a number of estimations shows that around 320,000 Hindus from East Pakistan had immigrated to Calcutta alone during 1946–1950 period.[citation needed]

The first census after partition shows that in Calcutta from 1941 to 1951 the number of Hindus increased while the number of Muslims decreased, that is Hindu percentage have increased from 73% in 1941 to 84% in 1951, while Muslim percentage have declined from 23% in 1941 to 12% in 1951 census.[49] According to 2011 census, Kolkata city have a Hindu majority of (76.51%), Muslims stand at (20.6%) as 2nd largest community, and Sikh population stands at (0.31%).[50]

Aftermath

[edit]During the riots, thousands began fleeing Calcutta. For several days the Howrah Bridge over the Hooghly River was crowded with evacuees headed for the Howrah station to escape the mayhem in Calcutta. Many of them would not escape the violence that spread out into the region outside Calcutta.[51] Lord Wavell claimed during his meeting on 27 August 1946 that Mahatma Gandhi had told him, "If India wants bloodbath she shall have it ... if a bloodbath was necessary, it would come about in spite of non-violence".[52]

There was criticism of Suhrawardy, Chief Minister in charge of the Home Portfolio in Calcutta, for being partisan and of Sir Frederick John Burrows, the British Governor of Bengal, for not having taken control of the situation. The Chief Minister spent a great deal of time in the Control Room in the Police Headquarters at Lalbazar, often attended by some of his supporters. Short of a direct order from the Governor, there was no way of preventing the Chief Minister from visiting the Control Room whenever he liked; and Governor Burrows was not prepared to give such an order, as it would clearly have indicated a complete lack of faith in him.[3] Prominent Muslim League leaders spent a great deal of time in police control rooms directing operations and the role of Suhrawardy in obstructing police duties is documented.[6] It was also reported Suhrawardy had sacked Hindu policemen on 16 August.[53] Both the British and Congress blamed Jinnah for calling the Direct Action Day and held the Muslim League responsible for stirring up the Muslim nationalist sentiment.[54]

There are several views on the exact cause of the Direct Action Day riots. The Hindu press blamed the Suhrawardy Government and the Muslim League.[55] According to the authorities, riots were instigated by members of the Muslim League and its affiliate Volunteer Corps,[3][20][16][21][56] in the city in order to enforce the declaration by the Muslim League that Muslims were to 'suspend all business' to support their demand for an independent Pakistan.[3][16][21][57]

However, supporters of the Muslim League claimed the Congress Party was behind the violence[58] in an effort to weaken the fragile Muslim League government in Bengal.[3] Historian Joya Chatterji allocates much of the responsibility to Suhrawardy, for setting up the confrontation and failing to stop the rioting, but points out that Hindu leaders were also culpable.[59] Members of the Indian National Congress, including Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru responded negatively to the riots and expressed shock. The riots would lead to further rioting and pogroms between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims.[38]

Further rioting in India

[edit]The Direct Action Day riots sparked off several riots between Muslims and Hindus/Sikhs in Noakhali, Bihar, and Punjab in that year:

Noakhali riots

[edit]An important sequel to Direct Action Day was the massacre in Noakhali and Tipperah districts in October 1946. News of the Great Calcutta Riot touched off the Noakhali–Tipperah riot in reaction. However, the violence was different in nature from Calcutta.[20][60]

Rioting in the districts began on 10 October 1946 in the area of northern Noakhali district under Ramganj police station.[61] The violence unleashed was described as "the organized fury of the Muslim mob".[62] It soon engulfed the neighbouring police stations of Raipur, Lakshmipur, Begumganj and Sandwip in Noakhali, and Faridganj, Hajiganj, Chandpur, Laksham and Chudagram in Tippera.[63] The disruption caused by the widespread violence was extensive, making it difficult to accurately establish the number of casualties. Official estimates put the number of dead between 200 and 300.[64][65] According to Francis Tuker, who at the time of the disturbances was General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Eastern Command, India, the Hindu press intentionally and grossly exaggerated reports of disorder.[65] The neutral and widely accepted death toll figure is around 5000.[66][67]

According to Governor Burrows, "the immediate occasion for the outbreak of the disturbances was the looting of a Bazar [market] in Ramganj police station following the holding of a mass meeting."[68] This included attacks on the place of business of Surendra Nath Bose and Rajendra Lal Roy Choudhury, the erstwhile president of the Noakhali Bar and a prominent Hindu Mahasabha leader.[69]

Mahatma Gandhi camped in Noakhali for four months and toured the district in a mission to restore peace and communal harmony. In the meantime, the Congress leadership started to accept the proposed Partition of India and the peace mission and other relief camps were abandoned. The majority of the survivors migrated to West Bengal, Tripura[70] and Assam.[71]

Bihar and rest of India

[edit]A devastating riot rocked Bihar towards the end of 1946. Between 30 October and 7 November, a large-scale massacre in Bihar brought the Partition closer to inevitability. Severe violence broke out in Chhapra and Saran district, between 25 and 28 October. Patna, Munger, and Bhagalpur quickly became sites of serious violence. Begun as a reprisal for the Noakhali riot, whose death toll had been greatly overstated in immediate reports, it was difficult for authorities to deal with because it was spread out over a large area of scattered villages, and the number of casualties was impossible to establish accurately: "According to a subsequent statement in the British Parliament, the death-toll amounted to 5,000. The Statesman's estimate was between 7,500 and 10,000; the Congress party admitted to 2,000; Jinnah claimed about 30,000."[72] However, by 3 November, the official estimate put the figure of death at only 445.[20][63]

According to some independent sources, the death toll was around 8,000.[73] Some of the worst rioting also took place in Garhmukteshwar in the United Provinces where a massacre occurred in November 1946, in which "Hindu pilgrims, at the annual religious fair, set upon and exterminated Muslims, not only on the festival grounds but in the adjacent town" while the police did little or nothing. The deaths were estimated at between 1,000 and 2,000.[74]

See also

[edit]- Bengali Nationalism

- Tebhaga movement

- Noakhali riots

- Bangladesh genocide

- Bengal Renaissance

- Partition of Bengal

- List of massacres in India

- Opposition to the partition of India

References

[edit]- ^ Sarkar, Tanika; Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2017). Calcutta: The Stormy Decades. Taylor & Francis. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-351-58172-1.

- ^ a b c Wavell, Archibald P. (1946). Report to Lord Pethick-Lawrence. British Library Archives: IOR.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Burrows, Frederick (1946). Report to Viceroy Lord Wavell. The British Library IOR: L/P&J/8/655 f.f. 95, 96–107.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Tanika; Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2018). Calcutta: The Stormy Decades. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-351-58172-1.

- ^ Zehra, Rosheena (16 August 2016). "Direct Action Day: When Massive Communal Riots Made Kolkata Bleed". TheQuint. Retrieved 31 August 2021.

- ^ a b Sengupta, Debjani (2006). "A City Feeding on Itself: Testimonies and Histories of 'Direct Action' Day" (PDF). In Narula, Monica (ed.). Turbulence. Serai Reader. Vol. 6. The Sarai Programme, Center for the Study of Developing Societies. pp. 288–295. OCLC 607413832.

- ^ L/I/1/425. The British Library Archives, London.

- ^ a b "The Calcutta Riots of 1946 | Sciences Po Mass Violence and Resistance – Research Network". www.sciencespo.fr. 4 April 2019.

- ^ Harun-or-Rashid (2003) [First published 1987]. The Foreshadowing of Bangladesh: Bengal Muslim League and Muslim Politics, 1906–1947 (Revised and enlarged ed.). The University Press Limited. pp. 242, 244–245. ISBN 984-05-1688-4.

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, pp. 318–319.

- ^ a b Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 216.

- ^ Wolpert 2009, pp. 360–361

- ^ Wolpert 2009, p. 361

- ^ Talbot & Singh 2009, p. 40.

- ^ Hardy 1972, p. 249.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nariaki, Nakazato (2000). "The politics of a Partition Riot: Calcutta in August 1946". In Sato Tsugitaka (ed.). Muslim Societies: Historical and Comparative Aspects. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-415-33254-5.

- ^ a b c d Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. Simon and Schuster. p. 15.

- ^ Guha, Ramachandra (23 August 2014). "Divided or Destroyed – Remembering Direct Action Day". The Telegraph (Opinion).

- ^ Tunzelmann, Alex von (2012). Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-1476-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Das, Suranjan (May 2000). "The 1992 Calcutta Riot in Historical Continuum: A Relapse into 'Communal Fury'?". Modern Asian Studies. 34 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1017/S0026749X0000336X. JSTOR 313064. S2CID 144646764.

- ^ a b c Das, Suranjan (2012). "Calcutta Riot, 1946". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009), The Partition of India, Cambridge University Press, p. 67, ISBN 978-0-521-67256-6,

(Signs of 'ethnic cleansing') were also present in the wave of violence that rippled out from Calcutta to Bihar, where there were high Muslim casualty figures, and to Noakhali deep in the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta of Bengal. Concerning the Noakhali riots, one British officer spoke of a 'determined and organized' Muslim effort to drive out all the Hindus, who accounted for around a fifth of the total population. Similarly, the Punjab counterparts to this transition of violence were the Rawalpindi massacres of March 1947. The level of death and destruction in such West Punjab villages as Thoa Khalsa was such that communities couldn't live together in its wake.

- ^ Jalal 1994, p. 176.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicholas; Moon, Penderel, eds. (1977). The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. VII. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 582–591. ISBN 978-0-11-580082-5.

- ^ Kulke & Rothermund 2004, p. 319.

- ^ a b

Azad, Abul Kalam (2005) [First published 1959]. India Wins Freedom: An Autobiographical Narrative. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-81-250-0514-8.

The resolution was passed with an overwhelming majority ... Thus, the [A.I.C.C.] seal of approval was put on the Working Committee's resolution accepting the Cabinet Mission Plan ... On 10 July, Jawaharlal held a press conference in Bombay ... [when questioned,] Jawaharlal replied emphatically that the Congress had agreed only to participate in the Constituent Assembly and regarded itself free to change or modify the Cabinet Mission Plan as it thought best ... The Moslem League had accepted the Cabinet Mission Plan ... Mr. Jinnah had clearly stated that he recommended acceptance.

- ^ Jalal 1994, p. 210.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2017). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan (New ed.). New Haven London: Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- ^ Hodson, H V (1997) [1969]. Great Divide; Britain, India, Pakistan. Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-577821-2.

- ^ Tuker, Francis (1950). While Memory Serves. Cassell. p. 153. OCLC 937426955.

From February onwards communal tension had been strong. Anti-British feeling was, at the same time, being excited by interested people who were trying to make it a substitute for the more important communal emotion. The sole result of their attempts was to add to the temperature of all emotions ... heightening the friction between Hindus and Muslims. Biased, perverted and inflammatory articles and twisted reports were appearing in Hindu and Muslim newspapers.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2017). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- ^ Tyson, John D. IOR: Tyson Papers, Eur E341/41, Tyson's note on Calcutta disturbances, 29 September 1946.

- ^

Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932–1947: Contour of Freedom. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-415-32889-0.

As a public holiday would enable 'the idle folk' successfully to enforce hartals in ares where the League leadership was uncertain, the Bengal Congress ... condemned the League ministry for having indulged in 'communal politics' for a narrow goal.

- ^ Tuker, Francis (1950). While Memory Serves. Cassell. pp. 154–156. OCLC 937426955.

As a counter-blast to this, Mr. K. Roy, leader of the Congress Party in the Bengal Legislative Assembly, addressing a meeting at Ballygunge on the 14th, said that it was stupid to think that the holiday [would] avoid commotions. The holiday, with its idle folk, would create trouble, for it was quite certain that those Hindus who, still wishing to pursue their business, kept open their shops, would be compelled by force to close them. From this there would certainly be violent disturbance. But he advised the Hindus to keep their shops open and to continue their business and not to submit to a compulsory hartal.

- ^ a b "Programme for Direct Action Day". Star of India. 13 August 1946.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay, Ritajyoti (2022). Streets in Motion: The Making of Infrastructure, Property, and Political Culture in Twentieth-century Calcutta. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76, 120–121. doi:10.1017/9781009109208. ISBN 978-1-009-10920-8. S2CID 250200020.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2017). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- ^ a b

Keay, John (2000). India: A history. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.

Suhrawardy ... proclaimed a public holiday. The police too, he implied, would take the day off. Muslims, rallying en masse for speeches and processions, saw this as an invitation; they began looting and burning such Hindu shops as remained open. Arson gave way to murder, and the victims struck back ... In October the riots spread to parts of East Bengal and also to UP and Bihar ... Nehru wrung his hands in horror ... Gandhi rushed to the scene, heroically progressing through the devastated communities to preach reconciliation.

- ^ Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. Simon and Schuster. p. 17.

... Seven lorries that came thundering down Harrison Road. Men armed with brickbats and bottles began leaping out of the lorries—Muslim 'goondas,' or gangsters, Nanda Lal decided, since they immediately fell to tearing up Hindu shops.

- ^ Tuker, Francis (1950). While Memory Serves. Cassell. pp. 159–160. OCLC 937426955.

At 6 p.m. curfew was clamped down all over the riot-affected districts. At 8 p.m. the Area Commander ... brought in the 7th Worcesters and the Green Howards from their barracks ... [troops] cleared the main routes ... and threw out patrols to free the police for work in the bustees.

- ^ "Looking back at the blood-curdling Calcutta Killings of 16th August 1946". 16 August 2019.

- ^ Sanyal, Sunanda; Basu, Soumya (2011). The Sickle & the Crescent: Communists, Muslim League and India's Partition. London: Frontpage Publications. pp. 149–151. ISBN 978-81-908841-6-7.

- ^ Sinha, Dinesh Chandra (2001). Shyamaprasad: Bangabhanga O Paschimbanga (শ্যামাপ্রসাদ: বঙ্গভঙ্গ ও পশ্চিমবঙ্গ). Kolkata: Akhil Bharatiya Itihash Sankalan Samiti. p. 127.

- ^ Tuker, Francis (1950). While Memory Serves. Cassell. p. 161. OCLC 937426955.

The bloodiest butchery of all had been between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. on the 17th, by which time the soldiers got the worst areas under control ... [From] the early hours of the 18th ... onwards the area of military domination of the city was increased ... Outside the 'military' areas, the situation worsened hourly. Buses and taxis were charging about loaded with Sikhs and Hindus armed with swords, iron bars and firearms.

- ^ Das, Suranjan (1991). Communal Riots in Bengal 1905–1947. Oxford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 0-19-562840-3.

- ^ Lambert, Richard (1951). Hindu-Muslim Riots. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, pp.179.

- ^ Horowitz, Donald L. (October 1973). "Direct, Displaced, and Cumulative Ethnic Aggression". Comparative Politics. 6 (1): 1–16. doi:10.2307/421343. JSTOR 421343.

- ^ "The Calcutta Riots of 1946 | Sciences Po Violence de masse et Résistance – Réseau de recherche". 4 April 2019.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay, Ritajyoti (2022). "City as Territory: Institutionalizing Majoritarianism" (PDF). Streets in Motion: The Making of Infrastructure, Property, and Political Culture in Twentieth-century Calcutta. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. doi:10.1017/9781009109208. ISBN 978-1-009-10920-8. S2CID 250200020.

- ^ "Home | Government of India". censusindia.gov.in.

- ^ Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. Simon and Schuster. p. 20.

Tousands began fleeting Calcutta. For days the bridge over the Hooghly River ... was a one-way current of men, women, children, and domestic animals, headed towards the Howrah railroad station ... But fast as the refugees fled, they could not keep ahead of the swiftly spreading tide of disaster. Calcutta was only the beginning of a chain reaction of riot, counter-riot, and reprisal which stormed through India.

- ^ Seervai, H. M. (1990). Partition of India: Legend and Reality. Oxford University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-19-597719-6.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2017). The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan. New Haven, CT: Yale University. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- ^ Sebestyen, Victor (2014), 1946: The Making of the Modern World, Pan Macmillan, p. 332, ISBN 978-1-4472-5050-0

- ^ Chatterji, Joya (1994). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-521-41128-8.

Hindu culpability was never acknowledged. The Hindu press laid the blame for the violence upon the Suhrawardy Government and the Muslim League.

- ^ Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932–1947: Contour of Freedom. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-415-32889-0.

The immediate provocation of a mass scale riot was certainly the afternoon League meeting at the Ochterlony Monument ... Major J. Sim of the Eastern Command wrote, 'there must have [been] 100,000 of them ... with green uniform of the Muslim National Guard' ... Suhrawardy appeared to have incited the mob ... As the Governor also mentioned, 'the violence on a wider scale broke out as soon as the meeting was over', and most of those who indulged in attacking Hindus ... were returning from [it].

- ^ "Direct Action". Time. 26 August 1946. p. 34. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

Moslem League Boss Mohamed Ali Jinnah had picked the 18th day of Ramadan for "Direct Action Day" against Britain's plan for Indian independence (which does not satisfy the Moslems' old demand for a separate Pakistan).

- ^ Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam, 1932–1947: Contour of Freedom. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-415-32889-0.

Having seen the reports from his own sources, he [Jinnah] was persuaded later, however, to accept that the 'communal riots in Calcutta were mainly started by Hindus and ... were of Hindu origin.'

- ^ Chatterji, Joya (1994). Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932–1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-521-41128-8.

Both sides in the confrontation came well-prepared for it ... Suhrawardy himself bears much of the responsibility for this blood-letting since he issued an open challenge to the Hindus and was grossly negligent ... in his failure to quell the rioting ... But Hindu leaders were also deeply implicated.

- ^ Batabyal, Rakesh (2005). Communalism in Bengal: From Famine to Noakhali, 1943–47. Sage Publishers. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-7619-3335-9.

The riot was a direct sequel to the Calcutta killings of August 1946, and therefore, believed to be a repercussion of the latter ... the Noakhali-Tippera riot ... was different in nature from the Calcutta killings ... news of the Calcutta killings sparked it off.

- ^ Batabyal, Rakesh (2005). Communalism in Bengal: From Famine to Noakhali, 1943–47. Sage Publishers. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-7619-3335-9.

Rioting in the districts ... began in the Ramganj Police Station area in the northern part of Noakhali district on 10 October 1946.

- ^ Ghosh Choudhuri, Haran C. (6 February 1947). Proceedings of the Bengal Legislative Assembly (PBLA). Vol. LXXVII. Bengal Legislative Assembly. cited in Batabyal 2005, p. 272.

- ^ a b Mansergh, Nicholas; Moon, Penderel (1980). The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. IX. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-11-580084-9. cited in Batabyal 2005, p. 272.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicholas; Moon, Penderel (1980). The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. IX. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-11-580084-9. cited in Batabyal 2005, p. 273.

- ^ a b Tuker, Francis (1950). While Memory Serves. Cassell. pp. 174–176. OCLC 186171893.

The number of dead was at that time reliably estimated as in the region of two hundred. On the other hand, very many Hindu families had fled, widespread panic existed, and it was impossible to say if particular individuals were dead or alive ... Hindus evacuated villages en masse, leaving their houses at the mercy of the robbers who looted and burned ... Our estimate was that the total killed in this episode was well under three hundred. Terrible and deliberately false stories were blown all over the world by a hysterical Hindu Press.

- ^ Khan, Yasmin (2017) [First published 2007]. The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan (New ed.). Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-300-23032-1.

- ^ "Written in Blood". Time. 28 October 1946. p. 42.

Mobs in the Noakhali district of east Bengal ... burned, looted and massacred on a scale surpassing even the recent Calcutta riots. In eight days an estimated 5,000 were killed.

- ^ Mansergh, Nicholas; Moon, Penderel (1980). The Transfer of Power 1942–7. Vol. IX. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-11-580084-9. cited in Batabyal 2005, p. 277.

- ^ Batabyal, Rakesh (2005). Communalism in Bengal: From Famine to Noakhali, 1943–47. Sage Publishers. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-7619-3335-9.

This included an attack on the 'Kutchery bari of Babu Suerndra Nath Bose and Rai Saheb Rajendra Lal Ray Choudhury of Karpara' ... the erstwhile president of the Noakhali Bar and a prominent Hindu Mahasabha leader in the district.

- ^ Dev, Chitta Ranjan (2005). "Two days with Mohandas Gandhi". Ishani. 1 (4). Mahatma Gandhi Ishani Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ Dasgupta, Anindita (2001). "Denial and Resistance: Sylheti Partition 'refugees' in Assam". Contemporary South Asia. 10 (3). South Asia Forum for Human Rights: 352. doi:10.1080/09584930120109559. S2CID 144544505. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- ^ Stephens, Ian (1963). Pakistan. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. p. 111. OCLC 1038975536.

- ^ Markovits, Claude (6 November 2007). "Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence". Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^ Stephens, Ian (1963). Pakistan. New York: Frederick A. Praeger. p. 113. OCLC 1038975536.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bourke-White, Margaret (1949). Halfway to Freedom: A Report on the New India in the Words and Photographs of Margaret Bourke-White. New York: Simon and Schuster. OCLC 10065226.

- Hardy, Peter (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-08488-1.

- Jalal, Ayesha (1994) [first published 1985]. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004) [First published 1986]. A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32919-4.

- Metcalf, Barbara D. A; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006) [First published 2001]. A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- Talbot, Ian; Singh, Gurharpal (2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4.

- Tsugitaka, Sato, ed. (2004). Muslim Societies: Historical and Comparative Aspects. New York: Routledge. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-0-203-40108-8.

- Wolpert, Stanley (2009) [First published 1977]. A New History of India (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516677-4.

- 1946 in British India

- 1946 murders in India

- 1946 protests

- 1946 riots

- 20th century in Kolkata

- 20th-century mass murder in India

- Attacks on shops in India

- August 1946 events in Asia

- Bengal Presidency

- Ethnic cleansing in Asia

- Massacres in 1946

- Massacres in India

- History of the All-India Muslim League

- Pakistan Movement

- Partition of India

- Hinduism-motivated violence in India

- Anti-Muslim violence in India

- Persecution of Hindus by Muslims

- Attacks on buildings and structures in the 1940s

- Pogroms

- Political terminology in Pakistan

- Religious riots in India

- Looting in India

- Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

- History of Bengal