Solvation

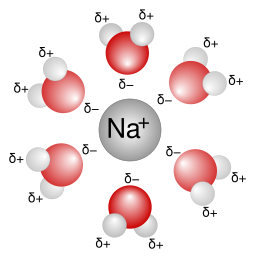

Solvations describes the interaction of a solvent with dissolved molecules. Both ionized and uncharged molecules interact strongly with a solvent, and the strength and nature of this interaction influence many properties of the solute, including solubility, reactivity, and color, as well as influencing the properties of the solvent such as its viscosity and density.[1] If the attractive forces between the solvent and solute particles are greater than the attractive forces holding the solute particles together, the solvent particles pull the solute particles apart and surround them. The surrounded solute particles then move away from the solid solute and out into the solution. Ions are surrounded by a concentric shell of solvent. Solvation is the process of reorganizing solvent and solute molecules into solvation complexes and involves bond formation, hydrogen bonding, and van der Waals forces. Solvation of a solute by water is called hydration.[2]

Solubility of solid compounds depends on a competition between lattice energy and solvation, including entropy effects related to changes in the solvent structure.[3]

Distinction from solubility

[edit]By an IUPAC definition,[4] solvation is an interaction of a solute with the solvent, which leads to stabilization of the solute species in the solution. In the solvated state, an ion or molecule in a solution is surrounded or complexed by solvent molecules. Solvated species can often be described by coordination number, and the complex stability constants. The concept of the solvation interaction can also be applied to an insoluble material, for example, solvation of functional groups on a surface of ion-exchange resin.

Solvation is, in concept, distinct from solubility. Solvation or dissolution is a kinetic process and is quantified by its rate. Solubility quantifies the dynamic equilibrium state achieved when the rate of dissolution equals the rate of precipitation. The consideration of the units makes the distinction clearer. The typical unit for dissolution rate is mol/s. The units for solubility express a concentration: mass per volume (mg/mL), molarity (mol/L), etc.[citation needed]

Solvents and intermolecular interactions

[edit]Solvation involves different types of intermolecular interactions:

- Hydrogen bonding

- Ion–dipole interactions

- The van der Waals forces, which consist of dipole–dipole, dipole–induced dipole, and induced dipole–induced dipole interactions.

Which of these forces are at play depends on the molecular structure and properties of the solvent and solute. The similarity or complementary character of these properties between solvent and solute determines how well a solute can be solvated by a particular solvent.

Solvent polarity is the most important factor in determining how well it solvates a particular solute. Polar solvents have molecular dipoles, meaning that part of the solvent molecule has more electron density than another part of the molecule. The part with more electron density will experience a partial negative charge while the part with less electron density will experience a partial positive charge. Polar solvent molecules can solvate polar solutes and ions because they can orient the appropriate partially charged portion of the molecule towards the solute through electrostatic attraction. This stabilizes the system and creates a solvation shell (or hydration shell in the case of water) around each particle of solute. The solvent molecules in the immediate vicinity of a solute particle often have a much different ordering than the rest of the solvent, and this area of differently ordered solvent molecules is called the cybotactic region.[5] Water is the most common and well-studied polar solvent, but others exist, such as ethanol, methanol, acetone, acetonitrile, and dimethyl sulfoxide. Polar solvents are often found to have a high dielectric constant, although other solvent scales are also used to classify solvent polarity. Polar solvents can be used to dissolve inorganic or ionic compounds such as salts. The conductivity of a solution depends on the solvation of its ions. Nonpolar solvents cannot solvate ions, and ions will be found as ion pairs.

Hydrogen bonding among solvent and solute molecules depends on the ability of each to accept H-bonds, donate H-bonds, or both. Solvents that can donate H-bonds are referred to as protic, while solvents that do not contain a polarized bond to a hydrogen atom and cannot donate a hydrogen bond are called aprotic. H-bond donor ability is classified on a scale (α).[6] Protic solvents can solvate solutes that can accept hydrogen bonds. Similarly, solvents that can accept a hydrogen bond can solvate H-bond-donating solutes. The hydrogen bond acceptor ability of a solvent is classified on a scale (β).[7] Solvents such as water can both donate and accept hydrogen bonds, making them excellent at solvating solutes that can donate or accept (or both) H-bonds.

Some chemical compounds experience solvatochromism, which is a change in color due to solvent polarity. This phenomenon illustrates how different solvents interact differently with the same solute. Other solvent effects include conformational or isomeric preferences and changes in the acidity of a solute.

Solvation energy and thermodynamic considerations

[edit]The solvation process will be thermodynamically favored only if the overall Gibbs energy of the solution is decreased, compared to the Gibbs energy of the separated solvent and solid (or gas or liquid). This means that the change in enthalpy minus the change in entropy (multiplied by the absolute temperature) is a negative value, or that the Gibbs energy of the system decreases. A negative Gibbs energy indicates a spontaneous process but does not provide information about the rate of dissolution.

Solvation involves multiple steps with different energy consequences. First, a cavity must form in the solvent to make space for a solute. This is both entropically and enthalpically unfavorable, as solvent ordering increases and solvent-solvent interactions decrease. Stronger interactions among solvent molecules leads to a greater enthalpic penalty for cavity formation. Next, a particle of solute must separate from the bulk. This is enthalpically unfavorable since solute-solute interactions decrease, but when the solute particle enters the cavity, the resulting solvent-solute interactions are enthalpically favorable. Finally, as solute mixes into solvent, there is an entropy gain.[5]

The enthalpy of solution is the solution enthalpy minus the enthalpy of the separate systems, whereas the entropy of solution is the corresponding difference in entropy. The solvation energy (change in Gibbs free energy) is the change in enthalpy minus the product of temperature (in Kelvin) times the change in entropy. Gases have a negative entropy of solution, due to the decrease in gaseous volume as gas dissolves. Since their enthalpy of solution does not decrease too much with temperature, and their entropy of solution is negative and does not vary appreciably with temperature, most gases are less soluble at higher temperatures.

Enthalpy of solvation can help explain why solvation occurs with some ionic lattices but not with others. The difference in energy between that which is necessary to release an ion from its lattice and the energy given off when it combines with a solvent molecule is called the enthalpy change of solution. A negative value for the enthalpy change of solution corresponds to an ion that is likely to dissolve, whereas a high positive value means that solvation will not occur. It is possible that an ion will dissolve even if it has a positive enthalpy value. The extra energy required comes from the increase in entropy that results when the ion dissolves. The introduction of entropy makes it harder to determine by calculation alone whether a substance will dissolve or not. A quantitative measure for solvation power of solvents is given by donor numbers.[8]

Although early thinking was that a higher ratio of a cation's ion charge to ionic radius, or the charge density, resulted in more solvation, this does not stand up to scrutiny for ions like iron(III) or lanthanides and actinides, which are readily hydrolyzed to form insoluble (hydrous) oxides. As these are solids, it is apparent that they are not solvated.

Strong solvent–solute interactions make the process of solvation more favorable. One way to compare how favorable the dissolution of a solute is in different solvents is to consider the free energy of transfer. The free energy of transfer quantifies the free energy difference between dilute solutions of a solute in two different solvents. This value essentially allows for comparison of solvation energies without including solute-solute interactions.[5]

In general, thermodynamic analysis of solutions is done by modeling them as reactions. For example, if you add sodium chloride to water, the salt will dissociate into the ions sodium(+aq) and chloride(-aq). The equilibrium constant for this dissociation can be predicted by the change in Gibbs energy of this reaction.

The Born equation is used to estimate Gibbs free energy of solvation of a gaseous ion.

Recent simulation studies have shown that the variation in solvation energy between the ions and the surrounding water molecules underlies the mechanism of the Hofmeister series.[9][1]

Macromolecules and assemblies

[edit]Solvation (specifically, hydration) is important for many biological structures and processes. For instance, solvation of ions and/or of charged macromolecules, like DNA and proteins, in aqueous solutions influences the formation of heterogeneous assemblies, which may be responsible for biological function.[10] As another example, protein folding occurs spontaneously, in part because of a favorable change in the interactions between the protein and the surrounding water molecules. Folded proteins are stabilized by 5-10 kcal/mol relative to the unfolded state due to a combination of solvation and the stronger intramolecular interactions in the folded protein structure, including hydrogen bonding.[11] Minimizing the number of hydrophobic side chains exposed to water by burying them in the center of a folded protein is a driving force related to solvation.

Solvation also affects host–guest complexation. Many host molecules have a hydrophobic pore that readily encapsulates a hydrophobic guest. These interactions can be used in applications such as drug delivery, such that a hydrophobic drug molecule can be delivered in a biological system without needing to covalently modify the drug in order to solubilize it. Binding constants for host–guest complexes depend on the polarity of the solvent.[12]

Hydration affects electronic and vibrational properties of biomolecules.[13][14]

Importance of solvation in computer simulations

[edit]Due to the importance of the effects of solvation on the structure of macromolecules, early computer simulations which attempted to model their behaviors without including the effects of solvent (in vacuo) could yield poor results when compared with experimental data obtained in solution. Small molecules may also adopt more compact conformations when simulated in vacuo; this is due to favorable van der Waals interactions and intramolecular electrostatic interactions which would be dampened in the presence of a solvent.

As computer power increased, it became possible to try and incorporate the effects of solvation within a simulation and the simplest way to do this is to surround the molecule being simulated with a "skin" of solvent molecules, akin to simulating the molecule within a drop of solvent if the skin is sufficiently deep.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b M. Andreev; J. de Pablo; A. Chremos; J. F. Douglas (2018). "Influence of Ion Solvation on the Properties of Electrolyte Solutions". J. Phys. Chem. B. 122 (14): 4029–4034. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b00518. PMID 29611710.

- ^ Cambell, Neil (2006). Chemistry - California Edition. Boston, Massachusetts: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 734. ISBN 978-0-13-201304-8.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 823. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "solvation". doi:10.1351/goldbook.S05747

- ^ a b c Eric V. Anslyn; Dennis A. Dougherty (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. ISBN 978-1-891389-31-3.

- ^ Taft R. W., Kamlet M. J. (1976). "The solvatochromic comparison method. 2. The .alpha.-scale of solvent hydrogen-bond donor (HBD) acidities". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 (10): 2886–2894. doi:10.1021/ja00426a036.

- ^ Taft R. W., Kamlet M. J. (1976). "The solvatochromic comparison method. 1. The .beta.-scale of solvent hydrogen-bond acceptor (HBA) basicities". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98 (2): 377–383. doi:10.1021/ja00418a009.

- ^ Gutmann V (1976). "Solvent effects on the reactivities of organometallic compounds". Coord. Chem. Rev. 18 (2): 225. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(00)82045-7.

- ^ M. Andreev; A. Chremos; J. de Pablo; J. F. Douglas (2017). "Coarse-Grained Model of the Dynamics of Electrolyte Solutions". J. Phys. Chem. B. 121 (34): 8195–8202. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b04297. PMID 28816050.

- ^ A. Chremos; J. F. Douglas (2018). "Polyelectrolyte association and solvation". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 149 (16): 163305. Bibcode:2018JChPh.149p3305C. doi:10.1063/1.5030530. PMC 6217855. PMID 30384680.

- ^ Pace, CN; Shirley, BA; McNutt, M; Gajiwala, K (1996). "Forces contributing to the conformational stability of proteins". FASEB Journal. 10 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.1.8566551. PMID 8566551. S2CID 20021399.

- ^ Steed, J. W. and Atwood, J. L. (2013) Supramolecular Chemistry. 2nd ed. Wiley. ISBN 1118681509, 9781118681503.

- ^ Mashaghi Alireza; et al. (2012). "Hydration strongly affects the molecular and electronic structure of membrane phospholipids". J. Chem. Phys. 136 (11): 114709. Bibcode:2012JChPh.136k4709M. doi:10.1063/1.3694280. PMID 22443792.

- ^ Bonn Mischa; et al. (2012). "Interfacial Water Facilitates Energy Transfer by Inducing Extended Vibrations in Membrane Lipids". J Phys Chem. 116 (22): 6455–6460. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.709.5345. doi:10.1021/jp302478a. PMID 22594454.

- ^ Leach, Andrew R. (2001). Molecular modelling : principles and applications (2nd ed.). Harlow, England: Prentice Hall. p. 320. ISBN 0-582-38210-6. OCLC 45008511.

Further reading

[edit]- Dogonadze, Revaz; et al., eds. (1985–88). The Chemical Physics of Solvation (3 vol. ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-42551-9 (part A), ISBN 0-444-42674-4 (part B), ISBN 0-444-42984-0 (Chemistry).

- Jiang D.; Urakawa A.; Yulikov M.; Mallat T.; Jeschke G.; Baiker A. (2009). "Size selectivity of a copper metal-organic framework and origin of catalytic activity in epoxide alcoholysis". Chemistry: A European Journal. 15 (45): 12255–62. doi:10.1002/chem.200901510. PMID 19806616. One example of a solvated MOF, where partial dissolution is described.

- Serafin, J.M. (October 2003). "Transfer Free Energy and the Hydrophobic Effect". J. Chem. Educ. 80 (10): 1194–1196. doi:10.1021/ed080p1194.