Congruence (geometry)

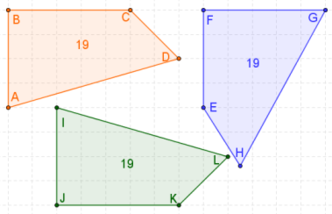

In geometry, two figures or objects are congruent if they have the same shape and size, or if one has the same shape and size as the mirror image of the other.[1]

More formally, two sets of points are called congruent if, and only if, one can be transformed into the other by an isometry, i.e., a combination of rigid motions, namely a translation, a rotation, and a reflection. This means that either object can be repositioned and reflected (but not resized) so as to coincide precisely with the other object. Therefore, two distinct plane figures on a piece of paper are congruent if they can be cut out and then matched up completely. Turning the paper over is permitted.

In elementary geometry the word congruent is often used as follows.[2] The word equal is often used in place of congruent for these objects.

- Two line segments are congruent if they have the same length.

- Two angles are congruent if they have the same measure.

- Two circles are congruent if they have the same diameter.

In this sense, two plane figures are congruent implies that their corresponding characteristics are "congruent" or "equal" including not just their corresponding sides and angles, but also their corresponding diagonals, perimeters, and areas.

The related concept of similarity applies if the objects have the same shape but do not necessarily have the same size. (Most definitions consider congruence to be a form of similarity, although a minority require that the objects have different sizes in order to qualify as similar.)

Determining congruence of polygons

For two polygons to be congruent, they must have an equal number of sides (and hence an equal number—the same number—of vertices). Two polygons with n sides are congruent if and only if they each have numerically identical sequences (even if clockwise for one polygon and counterclockwise for the other) side-angle-side-angle-... for n sides and n angles.

Congruence of polygons can be established graphically as follows:

- First, match and label the corresponding vertices of the two figures.

- Second, draw a vector from one of the vertices of one of the figures to the corresponding vertex of the other figure. Translate the first figure by this vector so that these two vertices match.

- Third, rotate the translated figure about the matched vertex until one pair of corresponding sides matches.

- Fourth, reflect the rotated figure about this matched side until the figures match.

If at any time the step cannot be completed, the polygons are not congruent.

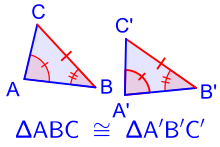

Congruence of triangles

Two triangles are congruent if their corresponding sides are equal in length, and their corresponding angles are equal in measure.

Symbolically, we write the congruency and incongruency of two triangles △ABC and △A′B′C′ as follows:

In many cases it is sufficient to establish the equality of three corresponding parts and use one of the following results to deduce the congruence of the two triangles.

Determining congruence

Sufficient evidence for congruence between two triangles in Euclidean space can be shown through the following comparisons:

- SAS (side-angle-side): If two pairs of sides of two triangles are equal in length, and the included angles are equal in measurement, then the triangles are congruent.

- SSS (side-side-side): If three pairs of sides of two triangles are equal in length, then the triangles are congruent.

- ASA (angle-side-angle): If two pairs of angles of two triangles are equal in measurement, and the included sides are equal in length, then the triangles are congruent.

The ASA postulate is attributed to Thales of Miletus. In most systems of axioms, the three criteria – SAS, SSS and ASA – are established as theorems. In the School Mathematics Study Group system SAS is taken as one (#15) of 22 postulates.

- AAS (angle-angle-side): If two pairs of angles of two triangles are equal in measurement, and a pair of corresponding non-included sides are equal in length, then the triangles are congruent. AAS is equivalent to an ASA condition, by the fact that if any two angles are given, so is the third angle, since their sum should be 180°. ASA and AAS are sometimes combined into a single condition, AAcorrS – any two angles and a corresponding side.[3]

- RHS (right-angle-hypotenuse-side), also known as HL (hypotenuse-leg): If two right-angled triangles have their hypotenuses equal in length, and a pair of other sides are equal in length, then the triangles are congruent.

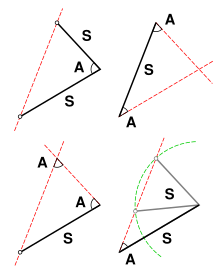

Side-side-angle

The SSA condition (side-side-angle) which specifies two sides and a non-included angle (also known as ASS, or angle-side-side) does not by itself prove congruence. In order to show congruence, additional information is required such as the measure of the corresponding angles and in some cases the lengths of the two pairs of corresponding sides. There are a few possible cases:

If two triangles satisfy the SSA condition and the length of the side opposite the angle is greater than or equal to the length of the adjacent side (SSA, or long side-short side-angle), then the two triangles are congruent. The opposite side is sometimes longer when the corresponding angles are acute, but it is always longer when the corresponding angles are right or obtuse. Where the angle is a right angle, also known as the hypotenuse-leg (HL) postulate or the right-angle-hypotenuse-side (RHS) condition, the third side can be calculated using the Pythagorean theorem thus allowing the SSS postulate to be applied.

If two triangles satisfy the SSA condition and the corresponding angles are acute and the length of the side opposite the angle is equal to the length of the adjacent side multiplied by the sine of the angle, then the two triangles are congruent.

If two triangles satisfy the SSA condition and the corresponding angles are acute and the length of the side opposite the angle is greater than the length of the adjacent side multiplied by the sine of the angle (but less than the length of the adjacent side), then the two triangles cannot be shown to be congruent. This is the ambiguous case and two different triangles can be formed from the given information, but further information distinguishing them can lead to a proof of congruence.

Angle-angle-angle

In Euclidean geometry, AAA (angle-angle-angle) (or just AA, since in Euclidean geometry the angles of a triangle add up to 180°) does not provide information regarding the size of the two triangles and hence proves only similarity and not congruence in Euclidean space.

However, in spherical geometry and hyperbolic geometry (where the sum of the angles of a triangle varies with size) AAA is sufficient for congruence on a given curvature of surface.[4]

CPCTC

This acronym stands for Corresponding Parts of Congruent Triangles are Congruent, which is an abbreviated version of the definition of congruent triangles.[5][6]

In more detail, it is a succinct way to say that if triangles ABC and DEF are congruent, that is,

with corresponding pairs of angles at vertices A and D; B and E; and C and F, and with corresponding pairs of sides AB and DE; BC and EF; and CA and FD, then the following statements are true:

The statement is often used as a justification in elementary geometry proofs when a conclusion of the congruence of parts of two triangles is needed after the congruence of the triangles has been established. For example, if two triangles have been shown to be congruent by the SSS criteria and a statement that corresponding angles are congruent is needed in a proof, then CPCTC may be used as a justification of this statement.

A related theorem is CPCFC, in which "triangles" is replaced with "figures" so that the theorem applies to any pair of polygons or polyhedrons that are congruent.

Definition of congruence in analytic geometry

In a Euclidean system, congruence is fundamental; it is the counterpart of equality for numbers. In analytic geometry, congruence may be defined intuitively thus: two mappings of figures onto one Cartesian coordinate system are congruent if and only if, for any two points in the first mapping, the Euclidean distance between them is equal to the Euclidean distance between the corresponding points in the second mapping.

A more formal definition states that two subsets A and B of Euclidean space Rn are called congruent if there exists an isometry f : Rn → Rn (an element of the Euclidean group E(n)) with f(A) = B. Congruence is an equivalence relation.

Congruent conic sections

Two conic sections are congruent if their eccentricities and one other distinct parameter characterizing them are equal. Their eccentricities establish their shapes, equality of which is sufficient to establish similarity, and the second parameter then establishes size. Since two circles, parabolas, or rectangular hyperbolas always have the same eccentricity (specifically 0 in the case of circles, 1 in the case of parabolas, and in the case of rectangular hyperbolas), two circles, parabolas, or rectangular hyperbolas need to have only one other common parameter value, establishing their size, for them to be congruent.

Congruent polyhedra

For two polyhedra with the same combinatorial type (that is, the same number E of edges, the same number of faces, and the same number of sides on corresponding faces), there exists a set of E measurements that can establish whether or not the polyhedra are congruent.[7][8] The number is tight, meaning that less than E measurements are not enough if the polyhedra are generic among their combinatorial type. But less measurements can work for special cases. For example, cubes have 12 edges, but 9 measurements are enough to decide if a polyhedron of that combinatorial type is congruent to a given regular cube.

Congruent triangles on a sphere

As with plane triangles, on a sphere two triangles sharing the same sequence of angle-side-angle (ASA) are necessarily congruent (that is, they have three identical sides and three identical angles).[9] This can be seen as follows: One can situate one of the vertices with a given angle at the south pole and run the side with given length up the prime meridian. Knowing both angles at either end of the segment of fixed length ensures that the other two sides emanate with a uniquely determined trajectory, and thus will meet each other at a uniquely determined point; thus ASA is valid.

The congruence theorems side-angle-side (SAS) and side-side-side (SSS) also hold on a sphere; in addition, if two spherical triangles have an identical angle-angle-angle (AAA) sequence, they are congruent (unlike for plane triangles).[9]

The plane-triangle congruence theorem angle-angle-side (AAS) does not hold for spherical triangles.[10] As in plane geometry, side-side-angle (SSA) does not imply congruence.

Notation

A symbol commonly used for congruence is an equals symbol with a tilde above it, ≅, corresponding to the Unicode character 'approximately equal to' (U+2245). In the UK, the three-bar equal sign ≡ (U+2261) is sometimes used.

See also

References

- ^ Clapham, C.; Nicholson, J. (2009). "Oxford Concise Dictionary of Mathematics, Congruent Figures" (PDF). Addison-Wesley. p. 167. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Congruence". Math Open Reference. 2009. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Parr, H. E. (1970). Revision Course in School mathematics. Mathematics Textbooks Second Edition. G Bell and Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-7135-1717-4.

- ^ Cornel, Antonio (2002). Geometry for Secondary Schools. Mathematics Textbooks Second Edition. Bookmark Inc. ISBN 971-569-441-1.

- ^ Jacobs, Harold R. (1974), Geometry, W.H. Freeman, p. 160, ISBN 0-7167-0456-0 Jacobs uses a slight variation of the phrase

- ^ "Congruent Triangles". Cliff's Notes. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- ^ Borisov, Alexander; Dickinson, Mark; Hastings, Stuart (March 2010). "A Congruence Problem for Polyhedra". American Mathematical Monthly. 117 (3): 232–249. arXiv:0811.4197. doi:10.4169/000298910X480081. S2CID 8166476.

- ^ Creech, Alexa. "A Congruence Problem" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Bolin, Michael (September 9, 2003). "Exploration of Spherical Geometry" (PDF). pp. 6–7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Hollyer, L. "Slide 89 of 112".

External links

- The SSS at Cut-the-Knot

- The SSA at Cut-the-Knot

- Interactive animations demonstrating Congruent polygons, Congruent angles, Congruent line segments, Congruent triangles at Math Open Reference