Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape

Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) is a training concept originally developed by the British during World War II. It is best known by its military acronym and prepares a range of Western forces to survive when evading or being captured. Initially focused on survival skills and evading capture, the curriculum was designed to equip military personnel, particularly pilots, with the necessary skills to survive in hostile environments. The program emphasised the importance of adhering to the military code of conduct and developing techniques for escape from captivity. Following the foundation laid by the British, the U.S. Air Force formally established its own SERE program at the end of World War II and the start of the Cold War. This program was extended to include the Navy and United States Marine Corps and was consolidated within the Air Force during the Korean War (1950–1953) with a greater focus on "resistance training."

In 1940, the British government established the Special Operations Executive (SOE) to train operatives in evasion and resistance techniques, supporting resistance movements in occupied Europe. These efforts throughout the 1940s laid the foundation for formal SERE programs, which focused on survival, evasion, and resistance, ensuring that military personnel were equipped to perform effectively under potential captivity scenarios.

During the Vietnam War (1959–1975), there was clear need for "jungle" survival training and greater public focus on American POWs. As a result, the U.S. military expanded SERE programs and training sites. In the late 1980s, the U.S. Army became more involved with SERE as Special Forces and "spec ops" grew. Today, SERE is taught to a variety of personnel based upon risk of capture and exploitation value with a high emphasis on aircrew, special operations, and foreign diplomatic and intelligence personnel.

History

Origins

The concept of SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape) training was first developed by the British during World War II. The United Kingdom initiated survival training for their aircrew, focusing on skills needed for evasion and survival in hostile environments. This laid the groundwork for the formalised SERE programs that were later expanded upon by other countries, including the United States.

During World War II, private citizens from France and Belgium created and financed escape and evasion lines as early as 1940 to help Allied soldiers and airmen stranded or shot down behind enemy lines evade capture by the German occupiers of western Europe.[1] Britain's MI9 Evasion and Escape ("E&E") organization began to help the escape lines once the British realized they could be effective. Led by World War I veteran Colonel (later Brigadier) Norman Crockatt,[2] MI9 were formed to train air crew and Special Forces in evading enemy troops following bail-out, forced landings, or being cut off behind enemy lines. A training school was established in London, and officers and instructors from MI9 also began visiting operational air bases, providing local training to air crews unable to be detached from their duties to attend formal courses. MI9 went on to devise a multitude of evasion and escape tools; These tools included overt items to aid immediate evasion after bailing out and covert items for use to aid escape following capture which were hidden within uniforms and personal items (concealed compasses, silk and tissue maps, etc.).

Once the United States entered the war in 1941, MI9 staff traveled to Washington, D.C., to discuss their now mature E&E training, devices, and proven results with the United States Army Air Forces ("USAAF"). As a result, the United States initiated their own Evasion and Escape organization, known as MIS-X, based at Fort Hunt, Virginia.

There were also several unofficial private "clubs" created during World War II by British and American pilots who had escaped from German forces during the war and returned to friendly lines. One such club was the "Late Arrivals' Club". This strictly nonmilitary club had a flying boot which was worn under the left collar of a uniform as its identifying symbol.

USAAF General Curtis LeMay realized that it was cheaper and more effective to train aircrews in Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape techniques than to have them lost in the arctic (or ocean) or languishing (or lost) in enemy hands. Thus, he supported the establishment of formal SERE training at several bases/locations (from July 1942 to May 1944) hosting the 336th Bombardment Group (now the 336th Training Group), including a small program for Cold Weather Survival at Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) Station Namao in Edmonton, Alberta where American, British, and Canadian B29 aircrews received basic survival training. In 1945, a consolidated survival training center was initiated at Fort Carson, Colorado, under the 3904th Training Squadron, and, in 1947, the Arctic Indoctrination Survival School (colloquially known as "the Cool School") opened at Marks Air Force Base in Nome, Alaska.

During WWII, the U.S. Navy discovered that 75% of its pilots who had been shot or forced down came down alive, yet barely 5% of them survived because they could not swim or find sustenance in the water or on remote islands. Since the ability to swim was an essential survival skill for Navy pilots, training programs were developed to ensure pilot trainees could swim (requiring cadets to swim one mile and dive 50 feet underwater to be able to escape bullets and suction from sinking aircraft). Soon, the training was expanded to include submerged aircraft escape.[3]

During the Korean War (1950–1953), the Air Force moved their survival school to Stead AFB, Reno Stead Airport as the 3635th Combat Crew Training Wing. In 1952, the United States Department of Defense (DoD) designated the United States Air Force (USAF) as executive agent (EA, as below) for joint escape and evasion.

The Korean War showed that traditional notions about captives during wartime were no longer valid as North Koreans, with Chinese backing, ignored the Geneva Conventions regarding treatment of POWs. This mistreatment was especially true for American airmen because of North Korean hatred of bombardments and airmen's prestige among soldiers. North Koreans were interested in the propaganda value of American captives given their new methods for gaining compliance, extracting confessions, and gathering information, which proved successful against American soldiers.[4][5]

A change in focus

Soon after the Korean War ended, the DoD initiated the Defense Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War to study and report on the problems and possible solutions regarding the Korean War POW fiasco. The charter of the committee was to find a suitable approach for preparing the U.S. armed forces to deal with the combat and captivity environment.[4]

The committee's key recommendation was the implementation of a military "Code of Conduct" that embodied traditional American values as moral obligations of soldiers during combat and captivity. Underlying this code was the belief that captivity was to be thought of as an extension of the battlefield; i.e., as a place where soldiers were expected to accept death as a possible duty.[6] President Eisenhower then issued Executive Order 10631 which stated: "All members of the Armed Forces of the United States are expected to measure up to the standards embodied in this Code of Conduct while in combat or in captivity." The U.S. military likewise began the process for training and implementing this directive.

While it was accepted that the Code of Conduct would be taught to all U.S. soldiers at the earliest point of their military training, the Air Force believed more was needed. At the USAF "Survival School" (Stead AFB), the concepts of evasion, resistance, and escape were expanded and new curricula were developed as "Code of Conduct Training". Those curricula have remained the foundation of modern SERE training throughout the U.S. military.

The Navy also recognized the need for new training, and by the late 1950s, formal SERE training was initiated at "Detachment SERE" Naval Air Station Brunswick in Maine with a 12-day Code of Conduct course designed to give Navy pilots and aircrew the skills necessary to survive and evade capture, and if captured, resist interrogation and escape. Later, the course was expanded so that other Navy and Marine Corps troops, such as SEALs, SWCC, EOD, RECON / MARSOC, and Navy Combat Medics would attend. Subsequently, a second school was opened at Naval Air Station North Island.[7] The Marine Corps opened their Pickel Meadow camp (initially established by Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton) in 1951, where Marines would be trained in outdoor survival and, later, opened the Mountain Warfare Training Center (MCMWTC) in Bridgeport, California, where training could be done in Level A SERE (as below). "Survival training" for soldiers has ancient origins as survival is a goal of combat.[8] Survival training was not distinct from "combat training" until navies realized the need to teach sailors to swim. Such training was not related to combat and was intended solely to help sailors survive. Similarly, firefighting training has long been a navy focus and remains so today (although survival of the ship may be the primary goal). Water survival training has been a distinct and formal part of Navy basic training since World War II, although its importance was greatly increased with the advent and expansion of naval aviation.[9]

In 1953, the Army established the "Jungle Operations Training Center" at Fort Sherman in Panama (known as "Green Hell"). Operations there were ramped up during the 1960s to meet the demand for jungle-trained soldiers in Vietnam.[10] In 1958, the Marine Corps opened Camp Gonsalves in northern Okinawa, Japan, where jungle warfare and survival training was offered to soldiers headed for Vietnam. As the Vietnam War progressed, the Air Force also opened a "Jungle Survival School" at Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

When Stead AFB closed in 1966, the USAF "survival school" was moved to Fairchild Air Force Base in Washington State (where it is centered today). The Air Force also had other survival schools including the "Tropical Survival School" at Howard Air Force Base in the Panama Canal Zone, the "Arctic Survival School" at Eielson Air Force Base, Alaska, and the "Water Survival School" at Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, which operated under separate commands. In April 1971, these schools were brought under the same Group and squadrons were organized to conduct training at Clark, Fairchild and Homestead, while detachments were used for other localized survival training (the acronym "SERE" was not used extensively in the Air Force until later in the 1970s).

In 1976, following accusations and reports of abuses during Navy SERE training, DoD established a committee (i.e., "Defense Review Committee") to examine the need for changes in Code of Conduct training. After hearing from experts and former POWs, they recommended the standardization of SERE training among all branches of the military and the expansion of SERE to include "lessons learned from previous US Prisoner of War experiences" (intending to make the training more "realistic and useful").[11]

In late 1984, the Pentagon issued DoD Directive 1300.7 which established three levels of SERE training with the "resistance portion" incorporated at "Level C". That level of training was specified for soldiers whose "assignment has a high risk of capture and whose position, rank, or seniority make them vulnerable to greater than average exploitation efforts by a captor".[12]

While initially only four military bases (Fairchild AFB, SERE), Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Naval Air Station North Island, and Camp Mackall (at Fort Bragg) were officially authorized to conduct Level C training, other bases have been added (such as Fort Novosel). Individual bases may conduct SERE courses which include C-level elements (see "Schools" below). The required (every 3 years) Level C refresher course is commonly taught by USAF "detachments" (often just one SERE specialist/instructor) stationed at a base or a traveling specialist.

As the designated executive agency for U.S. military SERE training, the USAF's 336th Training Group continues to provide the only U.S. military career SERE specialists and instructors who are part of Air Force Special Warfare Operations and are utilized in varied roles throughout the Air Force and DoD.[13][14][15] See USAF "Survival Instructors".

Selecting an Executive Agency

The DoD defines Executive Agency as "the Head of a DOD Component to whom the Secretary of Defense (SECDEF) or the Deputy Secretary of Defense (DEPSECDEF) has assigned specific responsibilities, functions, and authorities to provide defined levels of support for operational missions, or administrative or other designated activities that involve two or more of the DOD Components."[16] DoD chose the U.S. Air Force as its Executive Agency for joint escape and evasion in 1952 and it was therefore the candidate to be chosen as the EA for SERE and CoC training in 1979.[17] The Air Force remained EA for most survival, evasion, escape and rescue related matters until 1995. But, with the growing importance of personnel recovery (PR), the United States Department of Defense established the Joint Services Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Agency (JSSA) in 1991 and designated it the DoD EA for DoD Prisoner of War / Missing in Action (POW / MIA) matters. In 1994 the JSSA was designated as the central organizer and implementer for PR and the USAF as the EA for Joint Combat Search and Rescue (JCSAR) Combat search and rescue. In 1999, the JPRA Joint Personnel Recovery Agency was created as an agency under the Commander in Chief, US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) and was named the Office of Primary Responsibility (OPR) for DoD-wide PR matters. JPRA has been designated a Chairman's Controlled Activity since 2011.[18]

JPRA has its headquarters at Fort Belvoir and as organizing agency (OA) for all DoD "resistance" training, it has close ties with the 336th Training Group (which was given the role of organizing and operating the Personnel Recovery Academy or PRA).[19] JPRA and the PRA now coordinate PR activities and train PR/SERE globally with American allies making extensive use of USAF SERE experts.[20]

USAF "Survival Instructors"/SERE Specialists

The first USAF "survival instructors" were experienced civilian wilderness volunteers and USAF personnel with prior instructor experience (and they included a small cadre of "USAF Rescuemen", i.e. United States Air Force Pararescue). When the Army Air Force formed the Air Rescue Service (ARS) in 1946, the 5th Rescue Squadron conducted the first Pararescue and Survival School at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida. With the move to Stead AFB and the opening of a full-time survival school, the USAF initiated the military's only full-time, career survival instructor program (with the Air Force Specialty Code 921). By the time the Air Force opened the survival school at Fairchild AFB in 1966, it also opened a separate "Instructor Training Branch" (ITB) under the 3636th Combat Crew Training Squadron where all Air Force Survival Instructors received their specialist training, composed of six months of classroom and field training, and initial qualification rating, which was "Global Survival Instructor". They then had to complete six months of On-the-Job Training (OJT) before they were qualified to teach SERE (aka "Combat Survival Training" or "CST"). Years of additional training for added specialties (such as arctic, jungle, tropics, and water survival, "resistance training", and "academic instruction") yield some of the most trained personnel in the U.S. military.[21]

Currently, USAF SERE specialist/instructor training is conducted under the 66th Training Squadron at Fairchild AFB. After selection and qualification conducted at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas via a SERE specialist orientation course, potential SERE instructors are assigned to the 66th Training Squadron to learn how to instruct SERE in any environment: the "field" survival course at Fairchild,[14] the non-ejection water survival course at Fairchild AFB (which trains aircrew members of non-parachute-equipped aircraft), and the resistance training orientation course (which covers the theories and principles needed to conduct Level C Code of Conduct resistance training laboratory instruction). USAF SERE specialists also earn their jump wings at the United States Army Airborne School.[22] SERE Specialists who work in the "dunker" portion of the water survival course at Fairchild are certified through the Navy Salvage Dive Course.[23] The SERE training instructor "7-level" upgrade course is a 19-day course that provides SERE instructors with advanced training in barren Arctic, barren desert, jungle, and open-ocean environments.

The Air Force's SERE instructors play key roles in DoD-wide training and in implementing other branches SERE training programs; both the Navy and Army send their SERE instructors to take the basic 9-day SERE course (SV-80-A) taught by the 22nd TS since these other branches have no career option for SERE. Because the Air Force has the largest and best trained SERE staff, it assumes diverse roles DoD wide, such as furnishing SERE training for Red Flag exercises.[24]

Curriculum

SERE curriculum has evolved from being primarily focused on "outdoor survival training" to increasingly focus upon "evasion, resistance, and escape". Military survival training differs from typical civilian programs in several key areas:

- The anticipated military survival situation almost always begins with exiting a vehicle – an aircraft or ship. Thus, the scenario begins with exit strategies, practices, and means (ejecting, parachuting, underwater escape, etc.).

- Military survival training has greater focus on specialized military survival equipment, survival kits, signaling, rescue techniques, and recovery methods.

- Military personnel are almost always better prepared for survival situations because of obvious inherent risk in their activities (and their training and equipment). Conversely, military personnel are subject to a much wider variety of likely scenarios as any given mission may expose them to a wide variety of risks, environments, and injuries.

- In almost all military survival situations someone knows you're missing and will be looking for you with advanced equipment and pre-established protocols.

- Military survival often involves exposure to an enemy. The basic survival skills taught in SERE programs include common outdoor/wilderness survival skills such as firecraft,[25] sheltercraft,[26] first aid,[27] water procurement and treatment, food procurement (traps, snares, and wild edibles), improvised equipment, self-defense (natural hazards), and navigation (map and compass, etc.). More advanced survival training focuses on mental elements such as will to survive, attitude, and "survival thinking" (situational awareness, assessment, prioritization).

Military survival schools also teach unique skills such as parachute landings, basic and specialized signalling, vectoring a helicopter, use of rescue devices (forest-tree penetrators, harnesses, etc.), rough terrain travel, and interaction with indigenous peoples.

Combat survival

The military "has an obligation to the American people to ensure its soldiers go into battle with the assurance of success and survival. This is an obligation that only rigorous and realistic training, conducted to standard, can fulfill".[28] The U.S. Army has long taken survival training as an integral part of combat readiness (per FM 7-21.13 "The Soldier's Guide") and combat training is largely about an individual soldier's survival as opposed to the enemy's non-survival. "Survival", as a distinct part of modern military training, largely emerges in special environment operations (as shown in "Mountain Operations", FM 3-97.6, "Jungle School",[29][30] the Marine Corps' mountain warfare training center,[31] the Air Force's Desert and Arctic Survival Schools (as above), and the Navy's Naval Special Warfare Cold Weather Detachment Kodiak).

Certain skills have been identified that enhance every soldier's chance for survival (whether they are on the battlefield or not):

- Use weapons properly and effectively

- Move safely and efficiently through various terrains

- Navigate from one point to another given point on the ground

- Communicate as needed

- Perform first aid (evaluate, stabilize, and transport)

- Identify and react properly to hazards

- Select and utilize offensive and defensive positions

- Maintain personal health and readiness

- Evade, resist, and escape (aka "kidnapping and hostage survival")

- Know and utilize emergency procedures, survival equipment, and recovery systems

Military survival

Military personnel are often subject to enhanced risks and unique situations and, therefore, beyond basic combat skills and specialty skills, many U.S. military personnel receive training in survival skills specific to their assignment. Such general survival training may include the basics listed above along with:

- Special survival equipment and procedures (specific vehicle exiting, first aid kits, etc.)

- Communication devices, practices, and procedures

- Navigation devices (e.g. GPS)

- Specialty rescue devices (e.g. forest penetrator, personal lowering and hoisting devices, etc.)

- Special survival practices and procedures (shipboard firefighting, abandon ship procedures, liferafts, etc.)

- Preparing for survival (mission briefings, personal survival gear/kits, special knowledge, etc.)

- Situational awareness and assessment / Understanding the mission environment: hazards and opportunities

- Prioritizing needs and planning actions for personal protection, survival, and recovery (survival decisions)

- If an enemy is involved – evasion (camouflage, travel techniques, et al.).

- Signaling (radios, mirrors, fire/smoke, flares, markers)

- Rescue contact and recovery procedures

Evasion, resistance, and escape

Evading an enemy consists of certain well-known basic skills, but the military has an interest in not openly discussing its practices since this may assist an enemy.[32] Major militaries spend considerable time and energy preparing for evasion with extensive planning (routes, practices, pick-up points, methods, "friendlies", "chits", weapons, etc.). Some elements of hostile survival preparedness and teaching are classified. This is especially true for "resistance" training where one hopes to prepare those who might be captured for hardship, stress, abuse, torture, interrogation, indoctrination, and exploitation.[33]

The foundation for capture preparedness lies in knowing one's duty and rights if taken prisoner.[34] For American soldiers, this begins with the Code of the United States Fighting Force. It is:

- I am an American, fighting in the forces which guard my country and our way of life. I am prepared to give my life in their defense.

- I will never surrender of my own free will. If in command, I will never surrender the members of my command while they still have the means to resist.

- If I am captured, I will continue to resist by all means available. I will make every effort to escape and to aid others to escape. I will accept neither parole nor special favors from the enemy.

- If I become a prisoner of war, I will keep faith with my fellow prisoners. I will give no information nor take part in any action which might be harmful to my comrades. If I am senior I will take command. If not, I will obey the lawful orders of those appointed over me and will back them up in every way.

- When questioned, should I become a prisoner of war, I am required to give name, rank, service number, and date of birth. I will evade answering further questions to the utmost of my ability, I will make no oral or written statements disloyal to my country and its allies or harmful to their cause.

- I will never forget that I am an American, fighting for freedom, responsible for my actions, and dedicated to the principles which made my country free. I will trust in my God and in the United States of America.[35][36]

Training on how to survive and resist an enemy in the event of capture is generally based on past experiences of captives and prisoners of war. Thus, it is important to know who one's captors are likely to be and what to expect from them. Intelligence regarding such things is sensitive, but in the modern era, captives are less likely to enjoy the status of "prisoner of war" and so to gain protections under the Geneva Conventions.[37] American soldiers are still taught the standards of international law for humanitarian treatment in war, but they are less likely to receive those protections than to offer them. Because details cannot be offered, a few examples of well-known resistance methods provide clues as to the nature of resistance techniques:[38]

- Use of a tap code to secretly communicate between captives.

- When U.S. Navy Commander Jeremiah Denton was forced to appear at a televised press conference, he repeatedly blinked the word "T-O-R-T-U-R-E" with Morse code.

- The "code" of prisoners at the "Hanoi Hilton" Hỏa Lò Prison: "Take physical torture until you are right at the edge of losing your ability to be rational. At that point, lie, do, or say whatever you must do to survive. But you first must take physical torture."[39][40]

- A pilot POW who gave the name of comic book heroes when his captors demanded the name of his fellow pilots.[41]

- Much from The Great Escape (book).

The teaching of "resistance" is typically done in a "simulation laboratory" setting where "resistance training" instructors act as hostile captors and soldier-students are treated as realistically as possible as captives/POWs with isolation, harsh conditions, close confinement, stress, mock interrogation, and torture "simulations". While it is impossible to simulate the reality of hostile captivity, such training has proven very effective in helping those who have endured captivity know what to expect of their captivity and themselves under such conditions.[42][43]

Code of Conduct training levels

Under current DoD public policy, SERE Code of Conduct (aka "Resistance") training has three levels:[44]

- Level A: Entry level training. These are the Code of Conduct classes (now commonly taken online) required for all military personnel – normally at recruit training, "basic"[45] and "OCS" Officer Candidate School.[46]

- Level B: For those operating or expected to operate forward of the division rear boundary and up to the forward line of own troops (FLOT). Normally limited to aircrew of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, and Air Force. Level B focuses on survival and evasion, with resistance in terms of initial capture.

- Level C: For troops at a high risk of capture and whose position, rank, or seniority make them vulnerable to greater than average exploitation efforts by any captor. Level C training focuses on resistance to exploitation and interrogation, survival during isolation and captivity, and escape from hostiles (e.g., "prison camps").[47]

"Escape Training" has elements similar to evasion and resistance training – if details are revealed, it potentially helps adversaries. Much of this training has to do with observation, planning, preparation, and contingencies. And much of this comes from historical experience so public sources are revealing (such as the movies The Great Escape (film) and Rescue Dawn).

Special survival situations

1. Water (ocean, river, littoral) Survival: Military personnel are much more likely to find themselves in a water survival situation than others. How to survive in water is taught at Navy Recruit Training, Navy SUBSCOL Submarine Escape Training, the Air Force Water Survival Course and at a separate SoF Special Forces Professional Military Education (PME) courses. Featured in such courses are topics and exercises such as:[48]

- Underwater escape from vessel/vehicle (from submarines to aircraft)

- Water parachute landing

- Swimming out from under a parachute

- Dealing with rough water

- Boarding and getting out of a life raft

- Life in a raft

- Use of aquatic survival gear

- Aquatic environment hazards

- Aquatic environment first aid (seasickness, immersion injuries, animal injuries)

- Food and water procurement and preparation

- Drown-proofing, swimming, flotation

- Special Psychological Concerns

2. Arctic (sea ice, tundra) Survival: Air Force aircrews spend considerable time flying over arctic regions Polar Routes and while modern arctic survival situations are rare, the training remains useful and worthwhile because its content obviously relates to winter survival anywhere. All U.S. military branches have some type of cold/winter/mountain survival training originating from hard-learned lessons during the Korean War (see above and below). Dealing with cold conditions presents several unique content areas:

- Cold injuries:[49] frostbite, hypothermia, chilblains, immersion foot

- Snow/Ice/Cold Issues: snow blindness, avalanches/ice fall, icebergs, wind chill, shock therapy (internal or external)

- Staying Warm

- Why an igloo or snow cave is far better than a tent

- Firecraft

- Saving calories, burning calories, and finding calories.

- Arctic/Snow Travel

- Water

- Hazards of moisture/Keeping dry

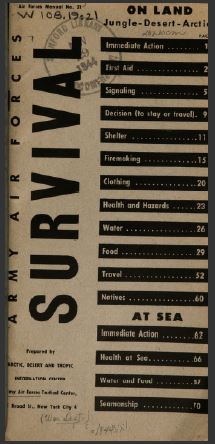

3. Desert Survival: While desert survival training was part of U.S. military survival courses since their inception (see Air Forces Manual No. 21)[50] the focus of survival training went that direction in 1990 with Operation Desert Shield Gulf War (1990–1991). Desert survival training is likely to remain a major focus in the foreseeable future. While there is a common mistake to think of deserts as hot, much of the Arctic (and Antarctic) is also polar desert. And under the definition of desert climate (a climate in which there is an excess of evaporation over precipitation), some deserts are deemed "cold weather deserts" such as the Gobi Desert.[51] Because the unifying feature of all deserts is a lack of water, that is the focus for desert survival:

- Conserve water (but don't over-do it): If it's hot, avoid perspiration; if it's cold, avoid dehydrating respiration[52]

- Understanding dehydration

- Water sources in arid regions

- Hot desert – shelter by day, move/act by night

- Cold desert – trap breath moisture

- Desert shelters (above or below surface)

- Desert garb

- Desert hazards and treatments

- Desert signaling

- Desert travel

4. Jungle/Tropics Survival: Staying alive in the jungle is relatively easy, but doing so comfortably can be very difficult. There are good reasons why soldiers deemed JWS (Jungle Warfare School) in Panama "Green Hell":[53]

- The jungle environment: conditions (wet, wetter, wettest)[54] heat index

- Jungle hazards

- Jungle ailments: trench foot, insect bites, bad food, bad water, parasites, snake bite

- Food

- Water preparation/treatment

- Jungle shelter(s)

- Firecraft

- Jungle improvisation

- Jungle signalling and rescue

5. Isolation Survival: Isolation is not just "being alone", it's being away from the familiar and comforting. Isolation survival has long been part of SERE in the "resistance" portion of training, but has more recently been recognized as worthy of broader attention. The psychological impact of suddenly finding yourself alone, lost, or outside your "comfort zone" can be debilitating, seriously depressing, and even fatal (via panic).[55] Isolation survival also focuses upon the broader view of captivity to include kidnapping and non-combatant captivity. Isolation survival training has more focus on psychological preparedness and less upon "skills".

- Understanding and avoiding panic

- The importance of "keeping your wits about you"

- Focus, Observe, Plan, and Envision ("FOPE")

- Stress[56] "fight or flight" coping response, the "stress cycle",[57] and things to help you stay calm.[58]

- The psychology of captivity[59]

U.S. military SERE/Survival Schools and courses

The vast majority of SERE/Survival Schools mentioned in "History" above are still operating. There has also been growth in private sector SERE Schools and training (which are not relevant herein). However, there has been a significant change in military use of private sector SERE training that is relevant here. That change has produced one odd outcome – the military has found it difficult to keep their well-trained and highly experienced SERE instructors because of lucrative private sector opportunities. The vast majority of those jobs require military SERE training.

Branch distinctions for SERE have become less clear or relevant since the creation of the Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA, as above). Because the JPRA has "primary responsibility for DoD-wide personnel recovery matters,"[18] (which specifically includes Level C SERE training), it integrates, coordinates, mandates, and draws from all military branches as needed. It is also worthy to note that much of military SERE is viewed as "joint operations" and cross-branch training is common (or required). SERE training detachments (usually, USAF) often work with different branches, especially where bases have been combined as "Joint Bases" and for update/review training. In that regard, designating schools by branch may be less meaningful.

- SERE 100.2 (J3TA-US1329) is a joint services Level A SERE education and training course supporting the military-wide "Code of Conduct" training requirement. It is 4 hour course available on-line or as an on-base classroom course.[60][failed verification]

It is common practice for joint operation SERE training to be conducted at, through, or in conjunction with individual military bases.[61]

U.S. Army

The Army position statement on SERE training is clear: "The Army has an obligation to the American people to ensure its soldiers go into battle with the assurance of success and survival. This is an obligation that only rigorous and realistic training, conducted to standard, can fulfill."[28] Like all military branches, the Army operates under DOD Directive 1300.7[12] which requires and specifies Code of Conduct training for military personnel. Because the Army views a large portion of its training as "survival" related and since the Army has more soldiers[62] than the other branches, there are many modes and schools for survival and SERE training (as indicated above and below). Army Airborne School, for example is largely about surviving parachute jumps but is not deemed a "survival school". US Army Green Berets, Army Rangers, Delta Force and other SoF soldiers receive extensive survival training as an inherent part of their overall combat training (as well as specific SERE training).

The mission of the United States Army SERE training is "to ensure each student gains the ability to effectively employ the SERE tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) necessary to return with honor regardless of the circumstances of separation, isolation or capture."[63]

The major "specialized schools" and courses for Army SERE training include:

- John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS) at Camp Mackall where Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) personnel complete their Special Forces Qualification Course (SFQC – Phase III "SF Tactical Combat Skills")[64] with a 19-day SERE course (including the Special Operations Forces' (ARSOF) Resistance Training Laboratory (RTL))[65] that includes Level C training.[66]

- Army Aviation School at Fort Novosel where 21 days of SERE training is included in the Army aviators curriculum. The program has a Level C course with both academics and resistance training labs.[67] The Basic Officer's Leadership Course (BOLC) includes introductory SERE training including Helicopter Over-water Survival Training (HOST). The SERE Level C course exposes students to various captor exploitation efforts including interrogation (eight methods), indoctrination, propaganda, video propaganda, concessions, forced labor, and reprisals. A simulated captivity environment provides experience which includes wartime, peacetime governmental detention, and hostage detention scenarios with content involving resistance postures, techniques and strategies, establishing overt and covert organizations, establishing overt and covert communications, and planning and executing escapes in captivity environments.[68]

- Northern Warfare Training Center (NWTC) at Black Rapids, Alaska (administered from Fort Wainwright) where several courses are intended to maintain the U.S. Army's abilities in cold weather and mountain warfare. The Cold Weather Orientation Course (CWOC),[69] Cold Weather Indoctrination Course (CWIC),[70] and Basic Military Mountaineering Course (BMMC)[71] each have specific "survival" sections.[72]

- Desert Warrior Course outside of Fort Bliss, Texas where a 20-day desert warfare course emphasizes the "individual strain on the body from the heat, sun, high winds and dryness." There is also special focus on desert hazards ("rattlesnakes, cobras, vipers, scorpions, tarantulas, camel spiders, coyotes, camels, big cats and antelope") and related medical skills.[73][74]

U.S. Navy

The USN Center for Security Forces (CENSECFOR) of the Naval Education and Training Command (NETC) at Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek–Fort Story promulgates the Navy's SERE training. The mission of the Command is "to educate and train those who serve, providing the tools and opportunities which enable life-long learning, professional and personal growth and development, ensuring fleet readiness and mission accomplishment; and to perform such other functions and tasks assigned by higher authority".[75] This includes basic survival training for all Navy sailors and DOD Directive 1300.7 requiring "Code of Conduct" training (as above). The major Navy SERE schools and courses include:

- The Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) School (A-2D-4635 or E-2D-0039) at CENSECFOR Detachment SERE East, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, New Hampshire offers several SERE courses including the outdoor/field course at the Navy Remote Training Site, Kittery, Maine, a "Risk of Isolation Brief" course, and the SERE Instructor Under Training course. The school employs approximately 100 military and civilian personnel and trains an average of 1,200 students per year.

- Cold Weather Environmental Survival Training (CWEST) at Rangeley, Maine – the US Navy's only cold weather survival school.

- The Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) School (A-2D-4635 or E-2D-0039) at CENSECFOR Detachment SERE West, Naval Air Station North Island, California provides all levels of "Code of Conduct" training for Recon Marines, Marine Corps Scout Snipers, MARSOC Marines, Navy SEALs, enlisted Navy and Marine aircrew, Naval Aviators, Naval Flight Officers, Naval Flight Surgeons, Navy EOD, and Navy SWCC. The school operates the Navy Remote Training Site at Warner Springs where sailors and marines learn basic skills necessary for worldwide survival, facilitating search and rescue efforts, and evading capture by hostile forces. Additional Level C Code of Conduct training includes a five-day Peacetime Detention and Hostage Survival (PDAHS) course providing skills to survive captivity by a hostile government or terrorist cell during peacetime.

- Recruit Training Command's Water Survival Division at Naval Station Great Lakes (NAVSTA Great Lakes), Illinois offers introductory survival training including: basic sea survival training; lifeboat organization, survival kit contents and usage, abandon ship procedures, and swim qualification (3rd class).

- Naval Special Warfare (NSW) SERE (K-431-0400), Naval Special Warfare Center, Coronado, California (mostly classified personnel recovery TTPs).

- Naval Aviation Survival Training Centers: The Navy operates eight water survival training centers for its aviators (Miramar, Jacksonville, Norfolk, Cherry Point, Pensacola, Patuxent River, Lemorre, and Whidbey Island).[76]

- Naval Special Warfare Advanced Training Command (NSWATC) courses (4) providing advanced training related to SERE and Personnel Recovery (PR) to Naval Special Warfare (NSW) trainees (SEAL/Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewman pipeline students and Combat Support/Combat Service Support (CS/CSS) personnel) and other select groups at Kodiak, Alaska and Virginia Beach, Virginia.

U.S. Air Force

The Air Education and Training Command (AETC) has over 60,000 personnel and is responsible for all Air Force training programs, including SERE training. In AETC, the 336th Training Group at Fairchild AFB, Washington has the mission to "provide high risk of isolation personnel with the skills and confidence to "Return With Honor" regardless of the circumstances of isolation."[77] It is also the largest U.S. Military SERE training provider training more than 20,000 students, in 19 different courses, each year."[78]

As with the other branches, the Air Force offers a wide scope of survival training within other courses, but unique to the Air Force is the stationing of career SERE specialists at bases around the world as renewal and upgrade SERE instructors, advisors, and PR specialists. In the mid-80s, the USAF Combat "Desert" Survival Course was established by the 3636th Combat Crew Training Wing and USAF Survival Training Schools began emphasizing "Combat SERE Training" (CST) instead of "Global SERE Training".[79] The primary Air Force survival schools/courses are:

- Arctic Survival School – the "Cool School" offered by the 66th TRS, Det. 1, at Eielson AFB, Alaska – a five-day course consisting of both classroom instruction and a 3-day field experience where students from all military branches along with "the Coast Guard, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other organizations that find their members operating in arctic conditions" get to build snow shelters, trap rabbits, and deal with being cold.[80]

- SERE Specialist Selection Course offered by the 66th TRS, Det. 3, at Lackland AFB, Texas – a rigorous pre-screening intended to save the Air Force time and money, and students needless pain and suffering.

- Evasion and Conduct After Capture (ECAC) Course, also conducted by the 66th TRS, Det. 3 at Lackland. A Level B code of Conduct course that may act as partial/preparation course for Level C Code of Conduct (completed elsewhere).

- Non-ejection Water Survival offered by the 22d TRS at Fairchild – a 2-day course with an obvious focus.

- SV-80-A – the USAF aircrew SERE course is the largest in the military with 6,000+ attendees in an average year. This 19-day course mixes classroom, field, and "laboratory" (captive simulation) experiences to prepare students to "Return with Honor". The course is the "standard" for Level C Code of Conduct training and is offered broadly beyond the Air Force.

- JPRA courses: The Personnel Recovery Academy is located with the SERE school at Fairchild and there is significant overlap in instruction and facility. The west coast JPRA facility is just across the highway at White Bluffs where separate Level C(+) training is offered (mostly classified).

- SV-81-A – the U.S. military's only career SERE Specialist Course is offered by the 66th TRS at the Air Force Survival School at Fairchild Air Force Base, Washington and other regional locations. After a grueling selection process, successful students relocate to Fairchild, where they experience what they will teach by completing the SV-80-A course. Then they undertake a series of challenging field training exercises over a 5 month period to develop broad first-hand knowledge and experience in different terrains, weather, and situations (and differing gear). Those who graduate (less than 10%) are awarded the Sage Beret (with insignia pin), SERE Arch and SERE Flash – only to enter another 45 weeks of intensive on-the-job training. At some point, graduates must complete Airborne School. After completion of 3–4 years as a "field instructor," specialists may be tasked to train students worldwide. USAF SERE specialists are encouraged to complete an associate degree in survival and rescue sciences through the USAF Community College to continue to advance in the SERE career field. (SERE Specialists complete additional qualification training at specialized schools as required. Examples are Scuba Courses, Military Freefall Parachuting, Altitude chamber, etc. Assignment to each of the outlying schools requires additional training by the SERE Specialist. Upon reporting to the new assignment, each SERE specialist must first complete that school's course (the same as an aircrew member), and then be trained by the school's cadre in the specialized subject matter (and carry crews under supervision) before the newly assigned specialist is "qualified" to teach without supervision. At Edwards AFB, USAF SERE specialists are tasked as "test parachutists" and required to perform multiple jumps on newly introduced / modified rescue systems, aircraft, and parachuting and / or ejection systems. This includes test parachuting newly designed canopies, harnesses, etc. Currently, they are the only test parachutists in the Department of Defense. USAF SERE specialists are considered DOD-wide subject matter experts in their field and are assigned to base level and command staff as advisers).[79][81]

- Combat Survival Training (CST) taught at the Air Force Academy (AFA) in Colorado. Since 2011, this program has been significantly reduced (following problems and controversies detailed below). With most academy graduates now required to attend the SV-80-A course at Fairchild, the AFA program is limited to some survival and Level B Code of Conduct training.[82][83] As of 2022, the course has been reintroduced to the AFA curriculum, with the intent of providing all AFA Cadets and select Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) Cadets with accredited Level B SERE training.[84]

Marine Corps

"Preserving the lives and well-being of U.S. military, Department of Defense (DoD) civilians, and DoD contractors authorized to accompany the force (CAAF) who are in danger of becoming, or already are beleaguered, besieged, captured, detained, interned, or, otherwise missing or evading capture (hereafter referred to as "isolated") while participating in U.S.-sponsored activities or missions, is one of the highest priorities of the DoD. The DoD has an obligation to train, equip, and protect its personnel, to prevent their capture and exploitation by adversaries, and to reduce the potential for the use of isolated personnel as leverage against U.S. security objectives. Personnel Recovery (PR) is the sum of military, diplomatic, and civil efforts to prepare for and execute the recovery and reintegration of isolated personnel." MSGID/GENADMIN/CG MCCDC QUANTICO VA REF/A/DODI O-3002.05//REF/B/CJCSM 3500.09//REF/C/MCO 3460.3| MARADMINS Number: 286/18 23 May 2018 announcing that "Training and Education Command (TECOM) in a joint effort with U.S. Army Forces Command, and with the assistance of the Joint Personal Recovery Agency, has developed a SERE Level A Training Support Package (TSP) that enables deploying units to self-train SERE Level A in an instructor guided group setting."

The U.S. Marine Corps operates jointly with the Navy and cooperatively with the other branches[85] in much of its SERE training, but operates its own Level C course at the Full Spectrum SERE Course, U.S. Marines Special Operations School (MSOS), Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Marine Spec Ops often train with Navy Spec Ops and utilize Navy training when it fits their needs and there is no equivalent USMC course. The Corps like to stand apart and have their own specifications for required "Code of Conduct" training:

Level A is taught to recruits and candidates in Officer Candidate School and the Recruit Depots, or under professional military education (but note the JPRA note above).

Level B is taught at the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center, Bridgeport, California, and at the North Training Area, Camp Gonsalves, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan.

Level C is held at Camp Lejeune, as above, although some Marine personnel are trained at the Navy facilities listed above.

USMC courses or training with survival focus include:

- Full Spectrum SERE Training taught by the MARSOC Personnel Recovery (PR)/ SERE Branch at Camp Lejeune provides 19 days of full spectrum Level C SERE training to MARSOC personnel encompassing Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTP) to plan for evasion, effect personnel recovery, survive and evade capture in austere environments and resist exploitation appropriately, in accordance with the Code of Conduct, should they become captured or detained. The training consists of classroom academic instruction, vicarious learning evolutions consisting of Academic Role-Play Laboratories (ARL), field survival exercises, an evasion exercise, experiential resistance training laboratories (RTL), an urban movement phase and a course debrief.[86]

- Mountain Warfare Training Center (MWTC) at Pickel Meadows in the Toiyabe National Forest (~20 miles northwest of Bridgeport, California) offers "specialized training in technical climbing, military mountaineering, snow mobility, field craft, survival, CASEVAC, navigation, use of pack animals and high angle marksmanship. Medical challenges include treatment of high altitude and cold weather illness and injuries, and casualty transport in a snow covered mountainous environment."[87]

- Special Operations Training Course (SOTC) is taught at the Marine Raider Training Center (MRTC) at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina in four phases under the general title Individual Training Course (ITC). The entire course includes six months of unhindered, realistic, challenging basic and intermediate Special Operations Forces (SOF) war fighting skills training. In the ten-week Phase I portion, Marines learn basic Spec Ops skills including SERE (Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape), TCCC (Tactical Combat Casualty Care), fire support training and communications. Survivability is a focus in all phases of the ITC course.[88]

- Jungle Warfare Training Center (JWTC) offers various courses taught by the 3d Marine Division at Camp Gonsalves, Okinawa, Japan. The skills, leaders, and endurance courses intend to teach Marines the skills they need should they become separated from their units in a combat zone and must survive off the land while evading the enemy.[89] The Jungle Tracking, Trauma, and Medicine Courses have more specific goals. The rigorous eight-day Basic Skills Course teaches skills such as first aid, communication, booby traps, knot tying, rappelling, and land navigation. Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape training (SERE) is conducted monthly and includes a 12-day course, 3 days of classroom learning of the basics of survival (how to identify and catch food, build tools, start fires and construct shelter), 5 days on a beach where the Marines survive on their own (with nothing but a knife, a canteen and the uniforms on their backs), and 4 days of "team" evasion through the muddy and tangled jungle (to avoid being captured by students from the man-tracking course). Captured student get placed into an improvised POW camp and the instructors interrogate them to test their "resistance" skills.[30]

Marines often participate in "exercises" and some of them have a survival focus.[61]

Allegations of misuse

President George W. Bush's January 2002 declaration that the Geneva Conventions regarding POWs did not apply to the conflict with Al-Qaeda or the Taliban as those "detainees" were not entitled to POW status or those legal guarantees of humane treatment [90] has led to serious problems for SERE training. The military Code of Conduct, based upon American adherence to the Geneva Conventions related to treatment of prisoners of war, gave American soldiers some legal and moral argument for their right to such protections. To soldiers who are legally required to follow the directives of their commander-in-chief, this declaration offered a potential excuse for harsh techniques or even torture by American personnel or those who captured Americans.[91] (As such, a soldier's claim that this was an "unlawful order" would be a difficult defense to establish because the specific legal definition of torture – "intended to inflict severe physical or mental pain or suffering" – remains unresolved in many contexts. An alleged torturer's intent is hard to prove, and the meaning of "severe" in this application is discretely debated as well.)[92][93]

From its origins in the 1950s, the "Resistance" portion of SERE was based upon a firm belief in and commitment to the protections of the Geneva conventions (as above). That opposing forces chose to ignore those protections was the very reason for creating the Code of Conduct and the ensuing development of "Resistance Training" (as above). However, some have argued that SERE's "Resistance" protocols were subverted by the U.S. military, and that it used Resistance-rooted training designed to help soldiers resist illegal and immoral means of torture for purposes of actively engaging in the torture of Guantanamo POWs. These allegations remain unproven, however, though some persist in conflating "SERE techniques" in misguided fashion with alleged incidents of "detainee interrogation/torture" by CIA and U.S. military personnel.

By definition, there are no "SERE techniques" involving torture: the "R" in SERE is about "Resistance training," intended solely to assist American POWs (or captives) in resisting unlawful force or methods intended to compel them to act against their fellow prisoners or their honor as soldiers. Nonetheless, the collective actions of the U.S. military as well as military contractors – including tangible proof of torture in some locations, most infamously Abu Ghraib – has raised questions over whether certain SERE techniques were inappropriately used.

Allegations of SERE training misuse

An online magazine article from June 2006 referenced a 2005 document obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union through the Freedom of Information Act in which the former chief of the Interrogation Control Element at Guantanamo Bay said "SERE instructors" taught their methods to interrogators of the prisoners in Cuba.[94] The article also stated that physical and mental techniques used against some detainees at Abu Ghraib Prison are similar to the ones SERE students are taught to resist.

According to Human Rights First, the interrogation that led to the death of Iraqi Major General Abed Hamed Mowhoush involved the use of techniques used in SERE training. Human Rights First claimed that "internal FBI memos and press reports have pointed to SERE training as the basis for some of the harshest techniques authorized for use on detainees by the Pentagon in 2002 and 2003."[95][96]

On June 17, 2008, Mark Mazzetti of The New York Times reported that the senior Pentagon lawyer Mark Schiffrin requested information in 2002 from the leaders of the Air Force's captivity-resistance program, referring to one based in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The information was later used on prisoners in military custody.[97] In written testimony presented in a Senate Armed Forces Committee hearing, Col. Steven Kleinman of the Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (JPRA) said a team of trainers whom he was leading in Iraq were asked to demonstrate SERE techniques on uncooperative prisoners. He refused, but his decision was overruled. He was quoted as saying, "When presented with the choice of getting smarter or getting tougher, we chose the latter."[98] Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has acknowledged that the use of the SERE program techniques to conduct interrogations in Iraq was discussed by senior White House officials in 2002 and 2003.[99]

It was subsequently confirmed that in 2002 JPRA was asked by the CIA to provide advisors on topics such as "deprivation techniques ... exploitation and questioning techniques, and developing countermeasures to resistance techniques."[100] While the identities of the alleged JPRA instructors have never been confirmed or denied, a number of media sources continued referring to them as "SERE instructors." JPRA has no direct relation to SERE, and many of its resistance training instructors are not SERE instructors (they are from the Air Force Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance Agency).

Senate Intelligence Committee report on CIA torture

On December 9, 2014, the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence released a report ("SASC report", hereafter) which detailed how contractors who developed the "enhanced interrogation techniques" used by U.S. personnel received US$81 million for their services and identified the contractors, who were referred to in the report via pseudonyms, as principals in Mitchell, Jessen & Associates from Spokane, Washington. Two of them were psychologists, John "Bruce" Jessen and James Mitchell. Jessen was a senior psychologist at the Defense Department who had worked with Army special forces in resistance training. The report states that the contractor "developed the list of enhanced interrogation techniques and personally conducted interrogations of some of the CIA's most significant detainees using those techniques. The contractors also evaluated whether the detainees' psychological state allowed for continued use of the techniques, even for some detainees they themselves were interrogating or had interrogated." Mitchell, Jessen & Associates developed a "menu" of 20 potential enhanced techniques including waterboarding, sleep deprivation and stress positions.[101]

Over the six years following their hiring, Mitchell, Jessen & Associates would hire over 100 staff, bill the CIA for over $80 million, and lead the American military (and other parts of the government) into one of their largest public relations fiascos in modern times. When 60 Minutes aired pictures from Abu Ghraib in May 2004, the shock was "heard around the world."[102] Americans, for the most part, began hearing of "SERE" for the first time during this period. While Mitchell, Jessen & Associates claim to have hired ex-"SERE instructors," it has never been established how many, if any, were ever legitimate SERE instructors; how many were, in reality, private contractors who used (or, more likely, misused) the title "SERE Instructor; or how many CIA operatives may have misleadingly referred to themselves as "SERE interrogators," solely because they used stolen and/or distorted SERE training techniques.[103] They were purportedly derived from classified training materials, both historical and instructional in nature, that were used for curriculum development in military and JPRA Level-C "resistance training."[104][105][106]

SERE abuses and scandals

- USAFA "sex abuse" during resistance training: See 2003 United States Air Force Academy sexual assault scandal. The United States Air Force Academy has had several sex/sex abuse scandals, some involving SERE. In 1993 a female cadet stated that she was particularly selected as a participant in a simulated rape and exploitation scenario where, while hooded and other cadets stood by, she had to lie on the ground with her shirt removed and her legs pried apart. The subsequent investigations failed to affirm the allegations and she filed a lawsuit[107] that was confidentially settled out-of-court.[108] In 1995, abuse allegations were made by one male cadet: "They dressed me up as a woman. They put me in a skirt, put makeup all over my face, and made me follow around one of the [instructors] like his little toy." The cadet also claimed that while he was tied to a bench, another cadet was forced to "get on top of me and act like he's having sex with me.".[109][110] Following this allegation, cadet SERE training was suspended until 1998 when it resumed without the "Sexual Exploitation" element.

- USN waterboarding during resistance training (ordered stopped in 2007 by JPRA): "For years, the U.S. military used waterboarding, a centuries-old torture technique, to train American troops to resist interrogation if captured."[111] JPRA (the controlling agency) compelled the Army and Navy to discontinue simulated waterboard training in 2007.

- Claims of psychological and/or physical harm from resistance training: It has been suggested that training exercises during SERE courses are harsh enough to cause students to become "psychologically defeated" and impaired in the ability to develop "psychological hardiness."[112]

- Claims of resistance training involving "torture": "The experience of torture at SERE [school] surely plays a role in the minds of the graduates who go on to be interrogators, and it must on some level help them rationalize their actions."[113] The most credible claim of simulations escalating into torture come from an internal JPRA memorandum regarding North Island SERE school waterboarding, which says, in part: "Out of the four water boards we observed, the instructor did not stop watering students when they started tapping their toes, but instead continued watering until stopped by the watch officer or until the totally defeated student gave an answer through the water. In one case two full canteen cups were poured after the student started tapping..." (The tapping of toes is an instructional signal given to students so they may temporarily stop the training simulation.)[112]

See also

- Survival skills

- Prisoner of war

- Special forces

- Special operations

- Personnel recovery

- Enhanced interrogation techniques

- Resistance to interrogation

- Special Activities Division

- Torture and the United States

- Survive, Evade, Resist, Extract – an analogous training program used by the armed forces of the United Kingdom

References

- ^ Foot, M. R. D.; Langley, J. M. (1980). MI9 Escape and Evasion. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0316288403.

- ^ Knighton, Andrew (22 June 2018). "Escape Master of WWII - Brigadier Norman Crockatt".

- ^ "Teaching America's WWII Navy Fighter Pilots to Swim". SwimSwam. 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Commentary - The military Code of Conduct: a brief history". 16 March 2013. Archived from the original on 16 March 2013.

- ^ Carlson, L., Remembered Prisoners of a Forgotten War: An Oral History of Korean War POWs, New York: St. Martin's (2002)

- ^ It wasn't until 1977 that the code was modified with the intent to make it more practical by removing or changing wording that implied death was often the most suitable course of action.

- ^ "Naval Air Station North Island".

- ^ "Every soldier, regardless of rank, position, and MOS must be able to shoot, move, communicate, and survive in order to contribute to the team and survive in combat." Army FM 7-21.13 ("The Soldier's Guide"), p. A-1

- ^ "US Navy Phase 1 Basic Military Training, aka US Navy Boot Camp". Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute. 14 February 2019.

- ^ Elphick, James (1 February 2018). "Why Jungle Warfare School was called a 'Green Hell'". www.wearethemighty.com. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "NVN: REVIEW OF THE CODE OF CONDUCT/Committee Recommends Changes in the PW Code of Conduct Based on Experiences of U.S. Servicemen Imprisoned in North Vietnam". Library of Congress.

- ^ a b "Department of Defense DIRECTIVE" (PDF). biotech.law.lsu.edu. 8 December 2000. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "SERE Specialists Working to Expand Their Ranks, Improve Recruitment". 1 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Inside Air Force SERE Specialist Training, America's Toughest Survival School". Men's Journal. 1 February 2019.

- ^ "Home Page". Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Department of Defense Executive Agent Responsibilities of the Secretary of the Army" (PDF). armypubs.army.mil. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ DoD Directive 1300.7; see also: "Return With Honor: Code of Conduct Training In the National Military Strategy Security Environment" by Maj. Laura M. Ryan, Thesis NPS, September 2004

- ^ a b "Joint Personnel Recovery Agency (Public Entry)". www.jpra.mil. Archived from the original on 6 February 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Personnel Recovery Academy". www.jpra.mil. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Personnel Recovery: Strategic Importance and Impact" by Pera, Miller, & Whitcomb, Air & Space Power Journal, Nov.–Dec. 2012, pp. 83-122 (A history of U.S. PR) at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/Volume-26_Issue-6/F-Pera-Miller-Whitcomb.pdf

- ^ "US Air Force SERE Specialist Selection & Training". Boot Camp & Military Fitness Institute. 28 March 2016.

- ^ Luckwaldt, Adam. "USAF SERE Specialist Career Profile". The Balance Careers.

- ^ "SERE: Water survival - preparing Airmen for the sea > Fairchild Air Force Base > Display". www.fairchild.af.mil. 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Preparing the best for the worst: SERE trains aircrews". www.mountainhome.af.mil. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ "US Army Survival Manual, FM 21-76, Chapter 7" at aircav.com

- ^ USAF AFR 64-4 Vol 1 Survival Manual, Ch. 15

- ^ USMC Survival, Evasion and Recovery MCRP 3-02H, Ch. 5

- ^ a b FM 7-21.13 ("The Soldier's Guide"), p. 5-2

- ^ Audrey McAvoy (7 August 2017). "Soldiers train for jungle warfare at Hawaii rainforest". Army Times. Associated Press.

- ^ a b Service, Marine Corps News. "What It's Like to Go Through Marine Corps SERE Training". The Balance Careers.

- ^ "Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center > About > History". www.29palms.marines.mil.

- ^ The release of a previously classified "PREAL" training guide provides detailed information-"DocumentCloud".

- ^ See "Evasion", pp. K-1 et seq. in JP 3-50 at https://fas.org/irp/doddir/dod/jp3_50.pdf

- ^ "Navy Legend Vice Adm. Stockdale Led POW Resistance | The Sextant". usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil. Archived from the original on 5 September 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ Code of Conduct, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Training, U.S. Army Regulation 350-30, 10 December 1985

- ^ USAFA 2010–2011 Contrails

- ^ "The Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 commentary" (PDF). Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

- ^ See "Lessons from the Hanoi Hilton: Six Characteristics of High Performance Teams" by Peter Fretwell, Taylor B. Kiland, Naval Institute Press (2013)

- ^ "Surviving Torture | Philadelphia Inquirer". 30 June 2009. Archived from the original on 30 June 2009.

- ^ "This Medal of Honor Recipient Was Executed for Singing "God Bless America"". 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Navy Legend Vice Adm. Stockdale Led POW Resistance". The Sextant. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "What I've Learned Since College: An interview with R. Dale Storr :: Fall 2006 :: Washington State Magazine". wsm.wsu.edu.

- ^ Carroll, Ward. "What It's Like At The Training Camp Where US Troops Learn To Survive If They Are Captured". Business Insider.

- ^ "Army Regulation 350–30: "Training Code of Conduct, Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE)"" (PDF). Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "Boot Camp – Today's Military". www.todaysmilitary.com.

- ^ "Joint Knowledge Online". jkosupport.jten.mil. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "SERE training develops leaders for complex environment". www.army.mil.

- ^ AFM 64-3 "Survival Training Edition"(1977); NAVAER 00-80T-56, "Survival Training Guide" (1955)

- ^ Nagpal, BM; Sharma, R (2004). "Cold Injuries : The Chill Within". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 60 (2): 165–171. doi:10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80111-4. PMC 4923033. PMID 27407612.

- ^ "Army Air Forces Survival on Land, at Sea". Training Aids Division. 2 July 1944 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Types of Deserts". pubs.usgs.gov.

- ^ Zieliński, Jakub; Przybylski, Jacek (2 July 2012). "How much water is lost during breathing?". Pneumonologia I Alergologia Polska. 80 (4): 339–342. doi:10.5603/ARM.27572. PMID 22714078. S2CID 9427084.

- ^ "Why Jungle Warfare School was called a 'Green Hell'". Americas Military Entertainment Brand. 1 February 2018.

- ^ "How to Survive in the Jungle". HowStuffWorks. 4 August 2008.

- ^ Diab, Emma (11 April 2016). "What Isolation Does to Your Brain (and How You Can Fight It)". Thrillist. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Heckman, William (8 November 2019). "Can stress kill you?".

- ^ "The Stress Response Cycle". psychcentral.com. 22 June 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Keeping Calm Under Pressure". Psychological Health Care. 14 November 2017.

- ^ Lieblich, A. (1994). Seasons of Captivity: The Inner World of POWs. NYU Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8147-5273-9. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ "DOD Has Taken Steps to Assess Common Military Training" (PDF). May 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Marines Learn Survival Skills in Scottish Highlands". U.S. Department of Defense. 2 October 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Personnel in United States Armed Forces major branches: U.S. Army 471,513, U.S. Navy 325,802, U.S. Air Force 323,222, U.S. Marine Corps 184,427

- ^ "SERE". Thomas Solutions Inc.

- ^ "Inside the SFQC | Special Forces Association". Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "CNN Programs – Presents". www.cnn.com.

- ^ Survival, Evasion Resistance and Escape (SERE) Course (Phase II SFQC) Archived 2018-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Army Special Operations Center of Excellence, last accessed 22 April 2017]

- ^ SERE training develops leaders for complex environment, Army.mil, by CPT Erik Olsen, dated 21 November 2014, last accessed 22 April 2017

- ^ "Resistance training". www.gd.com. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "NWTC". www.wainwright.army.mil. Archived from the original on 7 January 2003. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Cold Weather (CWLC, CWOC & CWIC) Student Handout api.army.mil

- ^ "Basic Military Mountaineering Course". www.army.mil.

- ^ "U.S. Special Forces Alpine Warfare Guide". Secrets of Survival. 5 August 2019.

- ^ Tan, Michelle (7 August 2017). "Army to launch new desert school". Army Times.

- ^ "Desert Warfare: 20-Day Course Focuses on Small-Unit Tactics". Association of the United States Army. 9 June 2016.

- ^ "Support services" (PDF). doni.documentservices.dla.mil. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ "ASTC Norfolk". Archived from the original on 21 September 2012.

- ^ "Units". www.gosere.af.mil.

- ^ "Home page of Fairchild Air Force Base". www.fairchild.af.mil.

- ^ a b "USAF Survival Evasion Resistance Escape | Baseops". Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "cool school". Airman Magazine.

- ^ "SERE specialists showcase training for recruiters". Joint Base San Antonio.

- ^ "USAFA Summer Training | Air Force ROTC". www.afrotc.msstate.edu.

- ^ "Air Force Academy Changes Simulated Rape Training After Complaints". AP NEWS.

- ^ e (14 July 2022). "Summertime course provides cadets combat survival training". United States Air Force Academy. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Air Force Special Tactics integrate into Marine Raider training". Air Force Special Tactics (24 SOW). 9 June 2017.

- ^ "Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command > Units > Marine Raider Training Center > SERE". www.marsoc.marines.mil.

- ^ "Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center > About > Mission". www.29palms.marines.mil. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Guide to MARSOC Training and Being a Marine Raider". Indeed Career Guide.

- ^ Careers, Full Bio Rod Powers was the U. S. Military expert for The Balance; Powers, was a retired Air Force First Sergeant with 22 years of active duty service Read The Balance's editorial policies Rod. "How to Survive Marine Corps Basic Training". The Balance Careers.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ III, John B. Bellinger (11 August 2010). "Obama, Bush, and the Geneva Conventions".

- ^ "Article 92 Failure to Obey an Order | Articles of UCMJ". Gary Myers, Daniel Conway and Associates.

- ^ Definition of Torture Under 18 U.S.C. §§ 2340–2340A justice.gov

- ^ Hyde, Alan (5 February 2007). "Torture as a Problem in Ordinary Legal Interpretation". Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ Benjamin, Mark (29 June 2006). "Torture teachers". Salon. Retrieved 19 July 2006.

- ^ Hina Shamsi; Deborah Pearlstein, ed. "Command's Responsibility: Detainee Deaths in U.S. Custody in Iraq and Afghanistan: Abed Hamed Mowhoush" Archived 2006-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights First, February 2006. Accessed 4 August 2008.

- ^ Department of Justice to Guantanamo Bay: From the Department of Justice to Guantanamo Bay : Administration lawyers and administration interrogation rules : Hearing before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the Committee on the Judiciary, One Hundred Tenth Congress, second session. U.S. Government Printing Office. 2008. pp. 219-221. ISBN 9780160831140.

- ^ Mark Mazzetti. "Ex-Pentagon Lawyers Face Inquiry on Interrogation Role". The New York Times, 17 June 2008.

- ^ Kleinman, Steven. "Officer: Military Demanded Torture Lessons". CBS News, 25 July 2008.

- ^ Rice, Condoleezza (26 September 2008). "Rice admits Bush officials held White House talks on CIA interrogations". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Beutler, Brian (24 April 2009). "Senate Report Accidentally Reveals SERE Instructors Trained CIA Officials In Torture". Talking Points Memo. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ See also: Report of the Office of the Inspector General (OIG): "Review of DoD-Directed Investigations of Detainee Abuse" (2006) at https://media.defense.gov/2016/May/19/2001774103/-1/-1/1/06-INTEL-10.pdf.

- ^ "Abuse At Abu Ghraib". www.cbsnews.com.

- ^ In sworn depositions, Mitchell states unequivocally and repeatedly that he didn't "design" or "develop" the North Korean/Chinese/Vietnamese techniques that he sold to the CIA (which became the basis for the "enhanced interrogation techniques"). See https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/176-1.-Exhibit-1.pdf

- ^ "Officer 'Unpopular' For Opposing Interrogations". NPR.org.

- ^ "It is both illegal and deeply unethical to use techniques that profoundly disrupt someone's personality" Leonard S. Rubenstein, the executive director of Physicians for Human Rights from "The Experiment | The New Yorker". The New Yorker.

- ^ "National Security Experts on Torture Report". Human Rights First.

- ^ "Saum v. Widnall, 912 F. Supp. 1384 (D. Colo. 1996)". Justia Law.

- ^ "The US Military's Forgotten Sex-Abuse Scandal That Foretold CIA Torture in the War on Terror". www.vice.com. 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Air Force Academy Changes Simulated Rape Training After Complaints". AP NEWS.

- ^ "Air Force To Tone Down Training Role Playing To Resist Sexual Abuse Went Too Far, Cadets Charge | The Spokesman-Review". www.spokesman.com.

- ^ Schulberg, Jessica (29 March 2018). "The Military Banned Waterboarding Trainees Because It Was Too Brutal – And Never Announced It". HuffPost.

- ^ a b "JPRA-Memo" (PDF). The Washington Post. 25 July 2002. Retrieved 26 July 2023.

- ^ Morris, David J. (29 January 2009). "The military should close its torture school. I know because I graduated from it". Slate.

Further reading

- "Department of Justice to Guantanamo Bay: From the Department of Justice to Guantanamo Bay : administration lawyers and administration interrogation rules : hearing before the Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties of the Committee on the Judiciary, One Hundred Tenth Congress, second session", United States. Congress. House. Committee on the Judiciary. Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties, U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008

- "Special Operations Forces Reference Manual", Fourth Edition, The JSOU Press, MacDill AFB, Florida, June 2015 at https://www.socom.mil/JSOU/JSOUPublications/2015SOFRefManual_final_cc.pdf

- Remembered Prisoners of a Forgotten War: An Oral History of Korean War POWs by Lewis H. Carlson, Macmillan (2002) – first-hand accounts of POWs.

- "Training Success for U.S. Air Force Special Operations and Combat Support Specialties: An Analysis of Recruiting, Screening, and Development Processes" by Maria C. Lytell, Sean Robson, David Schulker, Tracy C. McCausland, Miriam Matthews, Louis T. Mariano, Albert A. Robbert, RAND Corporation (2018)

- Beyond Survival: Building on the Hard Times, Gerald Coffee, Putnam (1990).[ISBN missing]

External links

- SERE Survival Training (Navy) - YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AERMhn1me_8

- Airmen Against the Sea: An Analysis of Sea Survival Experiences" by George Albert Llano (1956) Free Google Books

- Survival, Evasion, and Recovery – Multiservice Procedures for Survival, Evasion, and Recovery FM 21-76-1

- Army Regulation for Code of Conduct/ SERE Training

- Air Force Policy Directive (AFPD) 16-13 - SERE

- Instruction implementing Air Force Policy Directive 16-13 - SERE

- "Survival, Evasion. Resistance, and Escape (SERE) Training: Preparing Military Members for the Demands of Captivity", by Anthony P. Duran, Gary Hoyt, and Charles A. Morgan III, in Military Psychology: Clinical and Operational Applicalions, edited by Carrie H. Kennedy and Eric A. Zillmer, Guilford (2006)

- Interview of Malcolm Nance, Chief of Training US Navy SERE