Gliese 784

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Telescopium |

| Right ascension | 20h 13m 53.396s[1] |

| Declination | −45° 09′ 50.47″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 7.96[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | M0V[2] |

| B−V color index | 1.45[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −33.5±0.5[1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 778.331 mas/yr[1] Dec.: -159.939 mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 162.2171 ± 0.0225 mas[1] |

| Distance | 20.106 ± 0.003 ly (6.1646 ± 0.0009 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 9.01[3] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.58[4] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.58[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.06[5] L☉ |

| Temperature | 3,754±92[6] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.07±0.06[6] dex |

| Rotation | 48±12[7] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 1.0[2] km/s |

| Age | 0.85±0.4[8] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

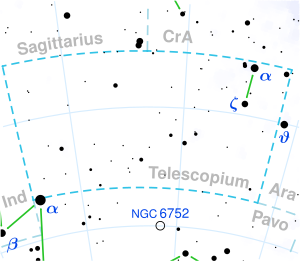

Location of Gliese 784 in the constellation Telescopium | |

Gliese 784 is a single[8] red dwarf star located in the southern constellation of Telescopium that may host an exoplanetary companion. The star was catalogued in 1900, when it was included in the Cordoba Durchmusterung (CD) by John M. Thome with the designation CD−45 13677.[10] It is too faint to be viewed with the naked eye, having an apparent visual magnitude of 7.96.[2] Gliese 784 is located at a distance of 20.1 light-years from the Sun as determined from parallax measurements, and is drifting closer with a radial velocity of −33.5 km/s.[1] The system is predicted to come as close as 11.4 light-years in ~121,700 years time.[11]

This is a small M-type main-sequence star with a stellar classification of M0V.[2] It is much younger than Sun at 0.85±0.4 billion years.[8] Despite this, it appears to be rotating slowly with a period of roughly 48 days.[7] The star has 58% of the mass and 58% of the radius of the Sun. It is radiating just 6%[5] of the luminosity of the Sun from its photosphere at an effective temperature of 3,754 K.[6]

Planetary system

In June 2019 one planet candidate was reported in orbit around Gliese 784.[12] An infrared excess was detected in 2020 that could suggest the presence of a circumstellar disk, but this is likely due to a background galaxy.[13]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (unconfirmed) | 9.4+4.6 −4.1 M🜨 |

0.059 ± 0.006 | 6.6592+0.0033 −0.0038 |

0.05+0.23 −0.05 |

— | — |

References

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, A. G. A.; et al. (Gaia collaboration) (2021). "Gaia Early Data Release 3: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 649: A1. arXiv:2012.01533. Bibcode:2021A&A...649A...1G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657. S2CID 227254300. (Erratum: doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039657e). Gaia EDR3 record for this source at VizieR.

- ^ a b c d e f Torres, C. A. O.; et al. (December 2006). "Search for associations containing young stars (SACY). I. Sample and searching method". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 460 (3): 695–708. arXiv:astro-ph/0609258. Bibcode:2006A&A...460..695T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065602. S2CID 16080025.

- ^ Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters. 38 (5): 331. arXiv:1108.4971. Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. S2CID 119257644.

- ^ "The One Hundred Nearest Star Systems". RECONS. Research Consortium On Nearby Stars. January 1, 2012. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c Gáspár, András; et al. (2016). "The Correlation between Metallicity and Debris Disk Mass". The Astrophysical Journal. 826 (2): 171. arXiv:1604.07403. Bibcode:2016ApJ...826..171G. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/826/2/171. S2CID 119241004.

- ^ a b c Hojjatpanah, S.; et al. (2019). "Catalog for the ESPRESSO blind radial velocity exoplanet survey". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 629: A80. arXiv:1908.04627. Bibcode:2019A&A...629A..80H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834729. S2CID 199552090.

- ^ a b Byrne, P. B.; Doyle, J. G. (January 1989). "Activity in late-type dwarfs. III. Chromospheric and transition region line fluxes for two dM stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 208: 159–165. Bibcode:1989A&A...208..159B.

- ^ a b c Brems, Stefan S.; et al. (2019), "Radial-velocity jitter of stars as a function of observational timescale and stellar age", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 632: A37, arXiv:1910.10389, Bibcode:2019A&A...632A..37B, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935520, S2CID 204838030

- ^ "HD 191849". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2021-11-22.

- ^ Thome, J. M. (1900). "Cordoba Durchmusterung declination -42 to -52". Resultados del Observatorio Nacional Argentino. 18: 1–502. (See also "Proper Motions of Some Stars in the General Catalogue Zona -42° -51°". Resultados del Observatorio Nacional Argentino. 18: 1. 1900. Bibcode:1900RNAO...18....1. Thome, Juan M. (1900). "Zonas de exploracion : Brillantez y posicion de todas las estrellas fijas hasta la decima magnitud comprendidas EN la faja del cielo entre 42 y 52 grados de declinacion sud". Resultados del Observatorio Nacional Argentino. 18. Bibcode:1900RNAO...18.....T. "Page 206 (CD-45 13677)". Archived from the original on 2019-12-15.

- ^ Bailer-Jones, C.A.L.; et al. (2018). "New stellar encounters discovered in the second Gaia data release". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 616: A37. arXiv:1805.07581. Bibcode:2018A&A...616A..37B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833456. S2CID 56269929.

- ^ a b Tuomi, M.; et al. (2019-06-11). "Frequency of planets orbiting M dwarfs in the Solar neighbourhood". arXiv:1906.04644v1 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Tanner, Angelle; et al. (2020), "Herschel Observations of Disks around Late-type Stars", Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 132 (1014): 084401, arXiv:2004.12597, Bibcode:2020PASP..132h4401T, doi:10.1088/1538-3873/ab895f, S2CID 216553868