Convair Kingfish

| Kingfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Kingfish concept art | |

| Role | Reconnaissance aircraft |

| National origin | United States of America |

| Manufacturer | Convair |

| Status | Cancelled |

| Primary user | Central Intelligence Agency |

| Number built | 0 |

The Convair Kingfish reconnaissance aircraft design was the ultimate result of a series of proposals designed at Convair as a replacement for the Lockheed U-2. Kingfish competed with the Lockheed A-12 for the Project Oxcart mission, and lost to that design in 1959.

Background

Problems with the U-2

Before the U-2 became operational in June 1956, CIA officials had estimated that improvements in Soviet air defences meant it would only be able to fly safely over the Soviet Union for between 18 months and two years.[1] After overflights began and the Soviets demonstrated the ability to track and attempt to intercept the U-2, this estimate was adjusted downward. In August 1956, Richard Bissell reduced it to six months.[2]

To extend the life of the U-2, the CIA implemented Project Rainbow, which added various countermeasures to confuse Soviet radars and make interception more difficult. There were two anti-radar methods. First, a diffusing coating for the fuselage; second, a series of wires strung along the fuselage and the wing edges intended to cancel radar reflections from the airframe by transmitting a similar return but out-of-phase. Several Rainbow-equipped flights were made, but the Soviets were able to track the aircraft. The weight of the equipment lowered the aircraft's maximum cruise altitude, making it more vulnerable to interception. Rainbow was cancelled in 1958.[3]

Replacing the U-2

As early as 1956 Bissell had already started looking for an entirely new aircraft to replace the U-2, with an emphasis on reducing the radar cross-section (RCS) as much as possible. High-altitude flight would still be useful to avoid interception by aircraft, but did little to help against missiles. By reducing the RCS, the radars guiding the missiles would have less time to track the aircraft, complicating the attack.

In August 1957 these studies turned to examining supersonic designs, as it was realized that supersonic aircraft were very difficult to track on radars of that era. This was due to an effect known as the blip-to-scan ratio, which refers to the "blip" generated by an aircraft on the radar display. In order to filter out random noise from the display, radar operators would turn down the amplification of the radar signal so that fleeting returns would not be bright enough to see. Returns from real targets, like an aircraft, would become visible as multiple radar pulses all drawn onto the same location on the screen, and produced a single, brighter spot. If the aircraft was moving at very high speeds, the returns would be spread out on the display. Like random noise, these returns would become invisible.

Project Gusto

By 1957 so many ideas had been submitted that Bissell arranged for the formation of a new advisory committee to study the concepts, led by Edwin H. Land under the designation Project Gusto.[4] The committee first met in November to arrange for submissions. At their next meeting, on 23 July 1958, several submissions were studied.

Kelly Johnson of Lockheed presented the Archangel I design, which could cruise at Mach 3 for extended periods to take advantage of blip/scan spoofing, although it was not designed for reduced RCS. Convair proposed a parasite aircraft that was launched in the air from a larger version of their B-58 Hustler that was then being studied, the B-58B. The Navy introduced a submarine-launched inflatable rubber vehicle that would be lifted to altitude by a balloon, boosted to speed by rockets, and then cruise using ramjets. Johnson was asked to provide a second opinion on the Navy design, and the committee arranged to meet again shortly.

At the next meeting, in September 1958, the designs had been further refined. Johnson reported on the Navy concept and demonstrated that it would require a balloon a mile wide for launching. The submission was then dropped. Boeing presented a new design for a 190-foot-long (58 m) liquid hydrogen powered inflatable design. Lockheed presented several designs; the Lockheed CL-400 Suntan looked like a scaled-up F-104 Starfighter powered by wingtip-mounted hydrogen-burning engines, the G2A was a subsonic design with a low radar cross-section, and the A-2 was a delta wing design using ramjets powered by zip fuel. Convair entered their parasite design, slightly upgraded and intended to fly at Mach 4.

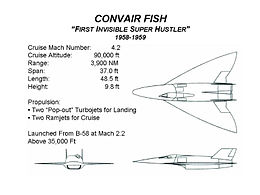

FISH

Convair's parasite design was derived from the Super Hustler concept that Convair had proposed to the Air Force. The original version had been a two-part design, the rear portion being an unmanned booster powered by a pair of ramjets, and the front portion a manned aircraft with a single ramjet. The Super Hustler could either be launched from under a B-58B Hustler bomber or from a ground trailer using a booster. For the air launch, the Super Hustler would be carried to a speed of Mach 2 at 35,000 ft (11,000 m), and released. All three ramjets would fire for "boost", after which the rear portion would fall away. The unmanned booster could also be used as a weapon, if armed.

For Project Gusto, the concept had been simplified and reduced to a single aircraft. Code-named FISH or First Invisible Super Hustler, the aircraft was based on a lifting body design that bears some resemblance to the ASSET spacecraft of a few years later. It differed in having the nose taper down to a flat horizontal line instead of the rounded delta of the ASSET, and the fuselage was not as large at the rear. Two vertical control surfaces were placed on either side of the fuselage at the rear, and a small delta wing covered about the rear third of the aircraft. It was to be powered by two Marquardt RJ-59 ramjets during the cruise phase, providing a cruise speed of Mach 4 at 75,000 ft (23,000 m), climbing to 90,000 ft (27,000 m) as it burned off fuel. To endure the intense heat generated by aerodynamic heating at these speeds, the leading edges of the nose and wings were built of a new "pyroceram" ceramic material, while the rest of the fuselage was made of a honeycomb structure stainless steel similar to the material for the proposed XB-70 Valkyrie. After completing its mission, the aircraft would return to friendly airspace, slow, and then open intakes for two small jet engines for the return flight at subsonic speeds.

Lockheed's entry had also changed during the research phase. Their original submission was the Archangel II (A-2), another ramjet-powered design, but one that was ground-launched using large jet engines.

The committee did not find either entry particularly interesting, and when the B-58B was cancelled by the Air Force in 1959, the entire FISH concept was put in jeopardy. There was some design work on converting the existing A-model Hustlers as FISH carriers, but the aircraft appeared to have limited capabilities for launching the FISH, and the Air Force was unwilling to part with any of their bombers. The committee asked both companies to return with another round of entries powered by the Pratt & Whitney J58 turbo-ramjet.

Kingfish

After cancellation of the B-58B in mid-1959, Convair turned to a completely new design, similar to their earlier entry in name only. The new "Kingfish" design had much in common with the Convair F-106 Delta Dart, using a classic delta wing layout like most of Convair's products. It differed in having two of the J58 engines buried in the rear fuselage, and twin vertical surfaces at the rear. The intakes and exhausts were arranged to reduce radar cross section, and the entire aircraft had the same sort of angular appearance as the later Lockheed F-117. The leading edges of the wings and intakes continued to use pyroceram, while other sections used a variety of materials selected for low radar reflection, including fiberglass. The new engines reduced the cruise speed to Mach 3.2, compared to Mach 4.2 for the FISH, but range was increased to about 3,400 nm (6,300 km).

In July 1959, Lockheed and Convair presented preliminary designs and cross selection estimates to the review panel. Lockheed's was designated the A-12, and was a variation of their A-11 design. President Eisenhower was briefed on 20 July and he approved moving ahead with a final decision. On 20 August, the companies presented their final designs for Kingfish and the A-12. Lockheed's design was estimated to have longer range, higher altitude and lower cost.[5] Johnson expressed skepticism of Convair's claimed RCS, and complained that they had given up performance to achieve it: "Convair have promised reduced radar cross section on an airplane the size of A-12. They are doing this, in my view, with total disregard for aerodynamics, inlet and afterburner performance."

On 28 August 1959, Johnson was notified that the A-12 had been selected. The decision was based not only on aircraft performance but also on contractor performance. During the U-2 project, Lockheed had proven its ability to design advanced aircraft in secret, on-time, and under-budget. In contrast, Convair had massive cost overruns with the B-58 and no secure R&D facility similar to the Skunk Works. Lockheed promised to lower the RCS in a modified version of the A-11 known as the A-12, and that sealed the deal. The A-12 entered service with the CIA in the 1960s, and was slightly modified to become the Air Force's SR-71.

Aftermath

Some small-scale work on the Kingfish continued even after the choice of the A-12, in case the A-12 ran into problems. This did not occur, and the Kingfish funds soon dried up.

The CIA continued studies into even higher performance aircraft, and studied replacing the A-12 under Project Isinglass. Isinglass focused on a new design blending features of the General Dynamics F-111 and Kingfish. The new design aimed to produce a reconnaissance aircraft capable of reaching up to Mach 5 at an altitude of 100,000 feet (30,000 m). The CIA decided that the extra performance would not be enough to protect it from missile systems already capable of attacking the A-12, and nothing came of the project.

The concept of spoofing radars through their blip/scan was ultimately ineffective. Among other issues, it was discovered that the engine exhaust produced significant reflections. Lockheed proposed adding cesium to the jet fuel to generate a cloud of ions that would help mask them.[6][7] In addition, since the spoofing relied on deficiencies in the radar display systems, upgrading them could render the entire concept moot. In the end, the A-12 was considered vulnerable and was only flown over secondary foes like Vietnam. The failure of the A-12's attempts to avoid radar was demonstrated when the Vietnamese proved able to track the A-12 with some ease, firing on several of them and causing minor damage on one occasion in 1967.[8][9]

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

Notes

Bibliography

- Johnson, Clarence L. "History of the OXCART Program." Archived 2015-09-19 at the Wayback Machine Burbank, California: Lockheed Aircraft Corporation Advanced Development Projects, SP-1362, 1 July 1968.

- "KINGFISH Summary Report." Fort Worth, Texas: Convair, PF-0-104M, 1959.

- Lovick, Edward, Jr. Radar Man: A Personal History of Stealth. New York: iUniverse, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4502-4804-4.

- McIninch, Thomas. "The Oxcart Story." Studies in Intelligence, Issue 15, Winter 1971 (Released: 6 May 2007). Retrieved: 10 July 2009.

- Merlin, Peter W. From Archangel to Senior Crown: Design and Development of the Blackbird. Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA), 2008. ISBN 978-1-56347-933-5.

- Pedlow, Gregory W. and Welzenbach, Donald E. "Chapter 6: The U-2's Intended Successor: Project Oxcart, 1956-1968." The Central Intelligence Agency and Overhead Reconnaissance: The U-2 and OXCART Programs, 1954 - 1974. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 1992. Retrieved: 2 April 2009.

- Scott, Jeff. "Convair Super Hustler, Fish & Kingfish." Aerospaceweb Question of the Week, 31 December 2006.

- Suhler, Paul A. From RAINBOW to GUSTO: Stealth and the Design of the Lockheed Blackbird. Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2009. ISBN 1-60086-712-X.

- "Super Hustler: A New Approach to the Manned Strategic Bombing-Reconnaissance Problem." Fort Worth, Texas: Convair, FMZ-1200-20, 26 May 1958.

- "Super Hustler SRD-17: TAC Bomber Studies." Fort Worth, Texas: Convair, FZM-1556B, 27 April 1960.

External links

- Hehs, Eric: Super Hustler, FISH, Kingfish, And Beyond codeonemagazine.com.