133rd Armored Division "Littorio"

| 133rd Armored Division "Littorio" | |

|---|---|

133rd Armored Division "Littorio" insignia | |

| Active | 6 November 1939 - 25 November 1942 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Armored |

| Size | Division |

| Part of | XX Army Corps German-Italian Panzer Army |

| Garrison/HQ | Parma |

| Engagements | World War II Italian invasion of France Invasion of Yugoslavia First Battle of El Alamein Battle of Alam el Halfa Second Battle of El Alamein |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol | Littorio Division gorget patches |

133rd Armored Division "Littorio" (Italian: 133ª Divisione corazzata "Littorio") was an armored division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The division's name derives from the fasces (Italian: Fascio littorio) carried by the lictors of ancient Rome, which Benito Mussolini had adopted as symbol of state-power of the fascist regime. Sent to North Africa in January 1942 for the Western Desert Campaign the division was destroyed in the Second battle of El Alamein in November 1942.[1]

History

Formation

The 133rd Armored Division "Littorio" was formed on 6 November 1939 in Parma by reorganizing parts of the 4th Infantry Division "Littorio", which had been made up of regular army "volunteer" and taken part in the Spanish Civil War. The Littorio was the third Italian armored division, after the 131st Armored Division "Centauro" and the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete".[2] Initially the Littorio fielded four tankette battalions, three Bersaglieri battalions, and two motorized artillery groups.[1] The Littorio's tank battalions were equipped with L3/35 tankettes, which by that time were already outdated and not suited for modern warfare.[3]

Invasion of France

On 10 June 1940 Italy entered World War II and began to invade France.[4] The Littorio and the 101st Motorized Division "Trieste" were sent to the Aosta Valley to exploit a planned breakthrough at the Little St Bernard Pass, which was to be achieved by the 1st Alpine Division "Taurinense" on the left flank and the 2nd Alpine Division "Tridentina" on the right flank, with the Trieste taking the pass itself. After the initial attacks had failed a tank battalion from the 33rd Tank Infantry Regiment was sent forward on 24 June 1940, but the Italian tankettes became bogged down in the rugged and snowy terrain. French anti-tank gunners then destroyed a number of Italian tankettes and the battalion withdrew. The same day the Franco-Italian Armistice came into effect and the war ended.[5]

Invasion of Yugoslavia

In late March 1941 the Littorio was transferred to the border with Yugoslavia for the Invasion of Yugoslavia. On 11 April 1941 the division crossed the border and advanced to Postojna. On 12 April the division reached Ogulin and on the 14 Šibenik on the Dalmatian Coast.[2] The Italians encountered minimal resistance by the Yugoslavian Seventh Army and on 16 April the Littorio met up with units of the 158th Infantry Division "Zara" in Knin and reached Mostar. On the 17 the Littorio reached Trebinje, where it met up with units of the 131st Armored Division "Centauro", which had advanced northward from Albania.[2] On 15 May 1941 the Littorio was repatriated.

Reorganization

In September 1941 the Littorio was reorganized. On 27 November 1941 the 33rd Tank Infantry Regiment with its obsolete tankettes was replaced by the 133rd Tank Infantry Regiment with more modern M13/40 and M14/41 tanks. The division also received the DLI and DLII self-propelled artillery groups with 75/18 self-propelled guns.[1]

Western Desert Campaign

In January 1942 the Littorio was ordered to Libya to reinforce the German-Italian Panzer Group Africa, which was fighting the Western Desert Campaign against the British Eighth Army. Due to British air and naval attacks originating in Malta the transfer of the division took months and was accompanied by severe losses of men and equipment.[6] The first units to arrive were the DLI and DLII self-propelled artillery battalion, which were immediately transferred to the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete" at the front. Meanwhile one transport carrying the tanks for one of the companies of the XII Tank Battalion was sunk by British warplanes in the Mediterranean and the ship carrying the XXXVI Bersaglieri Battalion was torpedoed by a British submarine and lost 2/3 of its men in the waters of the Mediterranean.[7]

On 27 January 1942 the Littorio had to cede its just debarked X Tank Battalion "M" to the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete", while the XII Tank Battalion had to cede all its remaining tanks to the divisions at the front. When the XI Tank Battalion "M" arrived in Tripolis it was immediately attached to the 101st Motorized Division "Trieste". The Littorio also lost part of its air defense, transport and artillery units to other divisions. By 31 May 1942 the Littorio had been sufficiently rebuild to be transferred to the front, where it was assigned to XX Army Corps.[1][6]

The Littorio did not participate in the Battle of Gazala, though British accounts usually include its troop and tank strengths in the Axis total. A battlegroup with two Bersaglieri battalions, two tank companies of the LI Tank Battalion and a battery of the CCCXXI Artillery Group arrived at the front on 20 June, and participated in the attack on Tobruk.[6] The division was a part of the investing force at Mersa Matruh, and pursued the British Eighth Army during its retreat to El Alamein. In this advance the division was harassed by the Desert Air Force, as all the Axis formations were, and it became engaged in a number of running fights with the British 1st Armoured Division.

First Battle of El Alamein

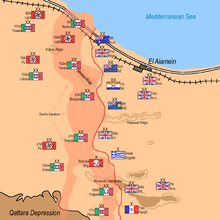

In the First Battle of El Alamein, the German commander Erwin Rommel planned for the 90th Light Division, 15th Panzer Division and 21st Panzer Division to penetrate the lines of the British Eighth Army between the Alamein box and Deir el Abyad. 90th Light was then to veer north to cut the coastal road and trap the Alamein defenders between the Axis forces and the sea. The Panzer Group Africa would veer right to attack the rear of British XIII Corps. The Italian XX Army Corps was to follow the German divisions and deal with the Qattara box, while the Littorio and German reconnaissance units would protect the right flank advances right flank.[8] The battalions of the Littorio were heavily engaged during the First Battle of El Alamein, with the XII Tank Battalion down to seven tanks by the end of the battle.[6]

Battle of Alam el Halfa

Rommel's second attempt to outflank the British positions at El Alamein commenced on 30 August 1942. The Battle of Alam el Halfa was started with an attack by the GermanAfrika Korps at dawn, which was quickly stopped by a flank attack from the British 8th Armoured Brigade. The Germans suffered little, as the British were under orders to spare their tanks for the coming offensive, but they could make no headway and were heavily shelled.[9] Meanwhile the Littorio and Ariete had moved up on the left of the Afrika Korps and the 90th Light Division and elements of Italian X Army Corps had drawn up to face the southern flank of the New Zealand box.[10] Under constant air raids throughout the day and night and on the morning of 2 September, Rommel realized that his offensive had failed and that staying in the salient would only add to his losses and ordered his forces to withdraw.[11]

Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein is usually divided into five phases, consisting of the break-in (23 to 24 October), the crumbling (24 to 25 October), the counter (26 to 28 October), Operation Supercharge (1 to 2 November) and the breakout (3 to 7 November). No name is given to the period from 29 to 31 October when the battle was at a standstill.

25 October 1942

Initially the Littorio was held in reserve behind the infantry divisions to the rear of Miteirya Ridge. On the 25 October the Axis forces launched a series of attacks using the 15th Panzer and Littorio divisions. The Panzer Group Africa was probing for a weakness, but found none. When the sun set the Allied infantry went on the attack and around midnight the British 51st (Highland) Division launched three attacks, but lost its way in the dark. The 15th Panzer and Littorio divisions held off the Allied armored units, but this proved costly and most units were severely depleted.[12] Rommel was convinced that the main assault would be in the north[13] and was determined to retake Point 29. He ordered a counterattack against Point 29 by 15th Panzer, 164th Light Africa Divisions and elements of XX Army Corps to begin at 1500 Hrs but under heavy artillery and air attack this came to nothing.[14] During the day he also started to draw his reserves to what was becoming the focal point of the battle: 21st Panzer and part of the Ariete moved north during the night to reinforce the 15th Panzer and Littorio and 90th Light Division at El Daba were ordered forward, while the Trieste division was ordered to move from Fuka to the front to replace them. 21st Panzer and the Ariete made slow progress during the night as they were heavily bombed.[15]

German records from 28 October 1942 reveal that the three divisions most affected were the 15th Panzer, 21st Panzer and Littorio divisions, which had lost 271 tanks since the start of the battle on the 23 October. This figure includes tanks out of action through mechanical failure as well as through mines or other battle damage, but by this time repairs and replacements were hardly keeping pace with daily losses. The surviving enemy tank states indicate that from the 28th to the 31st the two German divisions found it difficult to muster 100 tanks in running order between them, while Littorio had between 30 and 40.[16]

2 November 1942

At 1100Hrs on 2 November the remains of 15th Panzer, 21st Panzer and Littorio counterattacked the British 1st Armoured Division and the remains of British 9th Armoured Brigade, which were dug in with a screen of anti-tank guns and artillery, and had intensive air support. The counter-attack failed under a blanket of shells and bombs, resulting in a loss of some 100 tanks.[17] Fighting continued throughout 3 November and the British 2nd Armoured Brigade was stopped by the remnants of the Afrika Korps and last few tanks of the Littorio.[18]

4 November 1942

On 4 November the Littorio, Ariete and Trieste were destroyed in an attack by the British 1st Armoured Division and 10th Armoured Division. When it became obvious to Rommel that there would be little chance to hold anything between El Daba and the frontier he ordered a retreat, with the Italian units left behind to fight a rear-guard action.[19] The Littorio division was declared lost due to wartime events on 25 November 1942 and its remaining personnel was assigned to the Tactical Group "Ariete".[1]

Organization

Organization in Italy

133rd Armored Division "Littorio", in Parma[1]

133rd Armored Division "Littorio", in Parma[1]

- 12th Bersaglieri Regiment, in Reggio Emilia[7]

- Command Company

- XXI Bersaglieri Motorcyclists Battalion (reorganized as XXI Bersaglieri Support Weapons Battalion in September 1941)

- XXIII Auto-transported Bersaglieri Battalion

- XXXVI Auto-transported Bersaglieri Battalion

- 12th Anti-tank Company (47/32 anti-tank guns; entered the XXI Bersaglieri Support Weapons Battalion in September 1941)

- 12th Bersaglieri Motorcyclists Company (formed in September 1941)

- 33rd Tank Infantry Regiment, in Parma (replaced by the 133rd Tank Infantry Regiment on 27 November 1941)

- Command Company

- I Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- II Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- III Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- IV Tank Battalion "L" (L3/35 tankettes)

- 133rd Tank Infantry Regiment, in Pordenone (joined the division on 27 November 1941)

- Command Company

- X Tank Battalion "M" (M14/41 tanks)

- XI Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40 tanks)

- XII Tank Battalion "M" (M14/41 tanks)

- 133rd Artillery Regiment "Littorio", in Mantova (formed on 18 September 1939 by the depot of the 3rd Army Corps Artillery Regiment in Cremona)[20]

- Command Unit

- I Group (75/27 mod. 06 field guns)

- II Group (75/27 mod. 06 field guns)

- III Group (105/28 cannons; joined the regiment in August 1941)

- IV Mixed Group

- 2x Anti-aircraft batteries (90/53 anti-aircraft guns mounted on Breda 51 trucks)

- 2x Anti-aircraft batteries (20/65 mod. 35 anti-aircraft guns)

- Ammunition and Supply Unit

- III Anti-tank Battalion (formed in September 1941)

- 133rd Anti-tank Company (47/32 anti-tank guns; autonomous unit until September 1941)

- 143rd Anti-tank Company (47/32 anti-tank guns; autonomous unit until September 1941)

- 133rd Mixed Engineer Company (expanded to the XXXIII Mixed Engineer Battalion in September 1941)

- 133rd Medical Section

- 133rd Supply Section

- 133rd Transport Section (replaced by the 43rd Transport Section in September 1941)

- 85th Carabinieri Section

- 86th Carabinieri Section (left the division in September 1941)

- 133rd Field Post Office

- 12th Bersaglieri Regiment, in Reggio Emilia[7]

Organization in Libya

133rd Armored Division "Littorio"[1][6]

133rd Armored Division "Littorio"[1][6]

- 12th Bersaglieri Regiment[7]

- Command Company

- XXI Bersaglieri Support Weapons Battalion

- XXIII Auto-transported Bersaglieri Battalion

- XXXVI Auto-transported Bersaglieri Battalion

- 12th Bersaglieri Motorcyclists Company

- 133rd Tank Infantry Regiment

- Command Company

- IV Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40 tanks; arrived from the 31st Tank Infantry Regiment in June 1942)

- X Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40 tanks; transferred on 27 January 1942 to the 132nd Armored Division "Ariete")

- XI Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40 tanks; transferred on 2 April 1942 to the 101st Motorized Division "Trieste")

- XII Tank Battalion "M" (M14/41 tanks)

- LI Tank Battalion "M" (M13/40 tanks; arrived from the 31st Tank Infantry Regiment in May 1942)

- 133rd Artillery Regiment "Littorio"[20]

- Command Unit

- I Group (75/27 mod. 06 field guns)

- II Group (75/27 mod. 06 field guns)

- III Group (105/28 cannons)

- IV Mixed Group (renumbered DIII Anti-aircraft Group)

- 2x Anti-aircraft batteries (90/53 anti-aircraft guns mounted on Lancia 3Ro trucks)

- 5th Anti-aircraft Battery (20/65 mod. 35 anti-aircraft guns)

- 406th Anti-aircraft Battery (20/65 mod. 35 anti-aircraft guns)

- V Self-propelled Group (75/18 self-propelled guns; renumbered DLVI Self-propelled Group)

- VI Self-propelled Group (75/18 self-propelled guns; renumbered DLIX Self-propelled Group)

- DLIV Self-propelled Group (75/18 self-propelled guns; transferred in August 1942 from the 131st Artillery Regiment "Centauro")

- Ammunition and Supply Unit

- III Squadrons Group/ "Lancieri di Novara" (L6/40 tanks, armored reconnaissance)

- XXIX Anti-aircraft Group (8.8 cm Flak 37 anti-aircraft guns; formed by the 3rd Anti-aircraft Artillery Regiment and attached to the division)

- CCCXXI Artillery Group (100/17 mod. 14 howitzers; attached to the division)

- 133rd Mixed Engineer Company

- 133rd Medical Section

- 133rd Supply Section

- 85th Carabinieri Section

- 133rd Field Post Office

- 12th Bersaglieri Regiment[7]

Commanding officers

The division's commanding officers were:[1]

- Generale di Divisione Gervasio Bitossi (6 November 1939 - 7 July 1942)

- Generale di Brigata Emilio Becuzzi (8-31 July 1942)

- Generale di Divisione Carlo Ceriana-Mayneri (1 August 1941 - October 1942)

- Generale di Divisione Gervasio Bitossi (October - 25 November 1942)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bollettino dell'Archivio dell'Ufficio Storico N.II-3 e 4 2002. Rome: Ministero della Difesa - Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito - Ufficio Storico. 2002. p. 332. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Bennighof, Mike (2008). "Littorio at Gazala". Avalanche Press. Archived from the original on 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2009-04-06.

- ^ Iron Arm – Sweet, John Joseph Timothy; Stackpole Books, 2007, Page 84

- ^ Jowett, Philip S. The Italian Army 1940–45 (1): Europe 1940–1943. Osprey, Oxford – New York, 2000, pg. 5, ISBN 978-1-85532-864-8

- ^ Bocca, Giorgio (1996). Storia d'Italia nella guerra fascista 1940-1943. Milan: Mondadori. pp. 156–157. ISBN 88-04-41214-3.

- ^ a b c d e Del Pozo, Enzo. ""Littorio" - Una sintesi di pura gloria" (PDF). Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "12° Reggimento Bersaglieri". Regio Esercito. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Playfair Vol. III, p. 340

- ^ Fraser, p. 359.

- ^ Playfair, p. 387.

- ^ Carver, p. 67.

- ^ Playfair, P. 50.

- ^ Watson (2007), p.23

- ^ Playfair, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Playfair, p. 51.

- ^ "Alam Halfa and Alamein, Chapter 27 — The Fourth Day of Battle, pp 356–357". New Zealand electronic text centre.

- ^ Watson, p. 24.

- ^ Playfair, p. 71.

- ^ Zinder, Harry (16 November 1942). "A Pint of Water per Man". Time Magazine (16 November 1942). Archived from the original on September 26, 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ a b F. dell'Uomo, R. di Rosa (1998). L'Esercito Italiano verso il 2000 - Vol. Secondo - Tomo II. Rome: SME - Ufficio Storico. p. 166.

- Citations

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2000) [1962]. El Alamein (New ed.). Ware, Herts. UK: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 978-1-84022-220-3.

- Playfair, Major-General I.S.O.; and Molony, Brigadier C.J.C.; with Flynn R.N., Captain F.C. & Gleave, Group Captain T.P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1966]. Butler, J.R.M (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East, Volume IV: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

Bibliography

- George F. Nafziger – Italian Order of Battle: An organizational history of the Italian Army in World War II (3 vol)

- John Joseph Timothy Sweet – Iron Arm: The Mechanization of Mussolini's Army, 1920–1940

- Paoletti, Ciro (2008). A Military History of Italy. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-98505-9.