Sucralose

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

1,6-Dichloro-1,6-dideoxy-β-

D-fructofuranosyl-4-chloro- 4-deoxy-α-D-galactopyranoside | |

| Other names

1',4,6'-Trichlorogalactosucrose

Trichlorosucrose E955 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.054.484 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E955 (glazing agents, ...) |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H19Cl3O8 | |

| Molar mass | 397.64 g/mol |

| Melting point | 130 °C |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Sucralose is a no-calorie artificial sweetener which does not promote tooth decay, and is sold under the brand names Splenda and SucraPlus.[2][3] In the European Union, it is also known under the E number (additive code) E955. Sucralose is approximately 600 times as sweet as sucrose (table sugar),[4] twice as sweet as saccharin, and four times as sweet as aspartame. Unlike aspartame, it is stable under heat and over a broad range of pH conditions and can be used in baking or in products that require a longer shelf life. Since its U.S. introduction in 1999, sucralose has overtaken Equal in the $1.5 billion artificial sweetener market, holding a 62% market share.[5] According to market research firm IRI, as reported in the Wall Street Journal, Splenda sold $212 million in 2006 in the U.S. while Equal sold $48.7 million.[6] The success of sucralose-based products stems from its favorable comparison to other low calorie sweeteners in terms of taste, stability, and safety.[7]

History

Sucralose was discovered in 1976 by scientists from Tate & Lyle, working with researchers Leslie Hough and Shashikant Phadnis at Queen Elizabeth College (now part of King's College London).[8] The duo were trying to test chlorinated sugars as chemical intermediates. On a late-summer day, Phadnis was told to test the powder. Phadnis thought that Hough asked him to taste it, so he did.[8] He found the compound to be exceptionally sweet (the final formula was 600 times as sweet as sugar). They worked with Tate & Lyle for a year before settling down on the final formula.

It was first approved for use in Canada (marketed as Splenda) in 1991. Subsequent approvals came in Australia in 1993, in New Zealand in 1996, in the United States in 1998, and in the European Union in 2004. As of 2008, it had been approved in over 80 countries, including Mexico, Brazil, China, India and Japan.[9]

Production

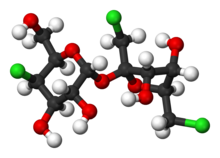

Tate & Lyle manufactures sucralose at a plant in McIntosh, Alabama, with additional capacity under construction in Jurong, Singapore. It is manufactured by the selective chlorination of sucrose (table sugar), in which three of the hydroxyl groups are replaced with chlorine atoms to produce sucralose. In May 2008, Fusion Nutraceuticals launched a brand called SucraPlus to compete against Tate & Lyle's Splenda. Sucralose is now also manufactured in India using the same technology as described in Tate & Lyle's now-expired patents.

Product uses

Sucralose can be found in more than 4,500 food and beverage products. Sucralose is used as a replacement for, or in combination with, other artificial or natural sweeteners such as aspartame, acesulfame potassium or high-fructose corn syrup. Sucralose is used in products such as candy, breakfast bars and soft drinks. It is also used in canned fruits wherein water and sucralose take the place of much higher calorie corn syrup based additives. Sucralose mixed with maltodextrin or dextrose (both made from corn) as bulking agents is sold internationally by McNeil Nutritionals under the Splenda brand name. In the United States and Canada, this blend is increasingly found in restaurants, including McDonalds, Tim Hortons and Starbucks, in yellow packets, in contrast to the blue packets commonly used by aspartame and the pink packets used by those containing saccharin sweeteners; though in Canada yellow packets are also associated with the SugarTwin brand of cyclamate sweetener.

Cooking

Sucralose is a highly heat-stable artificial sweetener, allowing it to be used in many recipes with little or no sugar. Sucralose is available in a granulated form that allows for same-volume substitution with sugar. This mix of granulated sucralose includes fillers, all of which rapidly dissolve in liquids.[citation needed] Unlike sucrose which dissolves to a clear state, sucralose suspension in clear liquids such as water results in a cloudy state. For example, gelatin and fruit preserves made with sucrose have a satiny, near jewel-like appearance, whereas the same products made with sucralose (whether cooked or not) appear translucent and marginally glistening.[citation needed] While the granulated sucralose provides apparent volume-for-volume sweetness, the texture in baked products may be noticeably different. Sucralose is non-hygroscopic, meaning it does not attract moisture, which can lead to baked goods that are noticeably drier and manifesting a less dense texture than baked products made with sucrose. Unlike sucrose which melts when baked at high temperatures, sucralose maintains its granular structure when subjected to dry, high heat (e.g., in a 350 °F (177 °C) oven). Thus, some baking recipes that require sugar sprinkled on top to partially or fully melt and crystallize (e.g., creme brulee), when substituting sucralose will not have the same surface texture, crispness, or crystalline structure.

Cooking strategies

- In 2008, McNeil Nutritionals in its Splenda granulated brand products recommended to home bakers to alter their recipes to replace one cup of sucrose with 3/4 cup granulated sucralose and 1/4 cup sucrose, in order to give a more authentic texture, moisture, and mouth feel to baked goods made with sucralose.

- The caloric load of traditional Southern sweet tea can be offset by substituting Splenda for 1/3 of the sugar ingredient typically used, thus adding a 2:1 sugar-sucralose mixture that preserves the integrity of traditional recipes.[10]

Packaging and storage

Most products that contain sucralose add fillers and additional sweetener to bring the product to the approximate volume and texture of an equivalent amount of sugar. This is because sucralose is nearly 600 times as sweet as sucrose (table sugar). Pure sucralose is sold in bulk, but not in quantities suitable for individual use, although some highly concentrated sucralose-water blends are available online, using 1/4 tsp per 1 cup of sweetness or roughly 1 part sucralose to 2 parts water.[11] Pure dry sucralose undergoes some decomposition at elevated temperatures. When it is in solution or blended with maltodextrin, it is slightly more stable.

Energy (caloric) content

Though marketed in the U.S. as a “No calorie sweetener,” Splenda products that also include bulking agents contain 12.4% the calories of the same volume of sugar.[12] When sucralose is added to commercial products such as diet drinks, the bulking agent is not present and no caloric energy is added.

Although the “nutritional facts” label on Splenda’s retail packaging states that a single serving of 1 gram contains zero calories, each individual, tear-open package or 1 gram serving contains 3.31 calories. Such labeling is appropriate in the U.S. because the FDA’s regulations permit a product to be labeled as “zero calories” if the “food contains less than 5 calories per reference amount customarily consumed and per labeled serving.”[13] Because Splenda contains a relatively small amount of sucralose, little of which is metabolized, virtually all of Splenda’s caloric content derives from the highly fluffed dextrose or maltodextrin bulking agents that give Splenda its volume. Like other carbohydrates, dextrose and maltodextrin have 3.75 calories per gram.

Health and safety regulation

Sucralose has been accepted by several national and international food safety regulatory bodies, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Joint Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization Expert Committee on Food Additives, The European Union's Scientific Committee on Food, Health Protection Branch of Health and Welfare Canada and Food Standards Australia-New Zealand (FSANZ). Sucralose is the only artificial sweetener ranked as "safe" by the consumer advocacy group Center for Science in the Public Interest.[14][15] According to the Canadian Diabetes Association, one can consume 15 mg/kg/day of Sucralose "on a daily basis over a ... lifetime without any adverse effects".[16] For a 150 lb person, 15 mg/kg is about 1 g, equivalent to about 75 packets of Splenda or the sweetness of 612 g or 2500 kcal of sugar.

“In determining the safety of sucralose, the FDA reviewed data from more than 110 studies in humans and animals. Many of the studies were designed to identify possible toxic effects including carcinogenic, reproductive and neurological effects. No such effects were found, and FDA's approval is based on the finding that sucralose is safe for human consumption.”[17] For example, McNeil Nutritional LLC studies submitted as part of its U.S. FDA Food Additive Petition 7A3987, indicated that "in the 2-year rodent bioassays...there was no evidence of carcinogenic activity for either sucralose or its hydrolysis products...."[18]

Splenda usually contains 95% dextrose (the "right-handed" isomer of glucose - see dextrorotation and chirality), which the body readily metabolizes. Splenda is recognized as safe to ingest as a diabetic sugar substitute.[19][20]

Public health and safety concerns

Results from over 100 animal and clinical studies in the FDA approval process unanimously indicated a lack of risk associated with sucralose intake.[8] However, some adverse effects were seen at doses that signficantly exceeded the estimated daily intake (EDI), which is 1.1 mg/kg/day.[21] When the EDI is compared to the intake at which adverse effects are seen, known as the highest no adverse effects limit (HNEL), at 1500 mg/kg/day,[21] there is a large margin of safety. The bulk of sucralose ingested does not leave the gastrointestinal tract and is directly excreted in the feces while 11-27% of it is absorbed.[4] The amount that is absorbed from the GI tract is largely removed from the blood stream by the kidneys and excreted in the urine with 20-30% of the absorbed sucralose being metabolized.[4]

Thymus

Some concern has been raised about the effect of sucralose on the thymus. A report from NICNAS cites two studies on rats, both of which found "a significant decrease in mean thymus weight" at high doses.[22] The sucralose dose which caused the effects was 3000 mg/kg/day for 28 days. For a 150 lb (68.2 kg) human, this would mean an intake of nearly 205 grams of sucralose a day, which is equivalent to more than 17,200 individual Splenda packets/day for approximately one month. The dose required to provoke any immunological response was 750 mg/kg/day,[23] or 51 grams of sucralose per day, which is nearly 4,300 Splenda packets/day.

Environmental effects

According to one study, sucralose is digestible by a number of microorganisms and is broken down once released into the environment.[24] However, measurements by the Swedish Environmental Research Institute have shown that wastewater treatment has little effect on sucralose, which is present in wastewater effluents at levels of several μg/L. [25]There are no known eco-toxicological effects at such levels, but the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency warns that there may be a continuous increase in levels if the compound is only slowly degraded in nature.[26]

Organochlorides

The basis for some of the concern about sucralose derives from the class of chemical to which it belongs. Sucralose is an organochloride (or chlorocarbon), some of which are known to cause adverse health effects in extremely small concentrations. Although some chlorocarbons are toxic, sucralose is not known to be toxic in small quantities and is extremely insoluble in fat; it cannot accumulate in fat like chlorinated hydrocarbons. In addition, sucralose does not break down or dechlorinate.[27] In contrast to these concerns, many organochlorides occur naturally in food sources such as seaweed.[28]

Other potential effects

One report suggests sucralose is a possible trigger for some migraine patients.[29] Another study published in the Journal of Mutation Research linked high doses (2000 mg/kg/day or 136 grams per day, which is more than 11,450 packets per day for the 150 lb person in the above example) of sucralose to DNA damage in mice.[30]

Allergic reactions to sucralose have not been documented, but individuals sensitive to either maltodextrin or dextrose should consult a physician about using any sweeteners containing these fillers.

Marketing controversy

In 2006 Merisant, the maker of Equal, filed suit against McNeil Nutritionals in federal court in Philadelphia alleging that Splenda's tagline "Made from sugar, so it tastes like sugar" is misleading. McNeil argued during the trial that it had never deceived consumers or set out to deceive them, since the product is in fact made from sugar. Merisant asked that McNeil be ordered to surrender profits and modify its advertising. The case ended with an agreement reached outside of court, with undisclosed settlement conditions.[31] The lawsuit was the latest move in a long-simmering dispute. In 2004, Merisant filed a complaint with the Better Business Bureau regarding McNeil's advertising. McNeil alleged that Merisant's complaint was in retaliation for a ruling in federal court in Puerto Rico, which forced Merisant to stop packaging Equal in packages resembling Splenda's. McNeil filed suit in Puerto Rico seeking a ruling which would declare its advertising to not be misleading. Following Merisant's lawsuit in Philadelphia, McNeil agreed to a jury trial and to the dismissal of its lawsuit in Puerto Rico.[6]

In 2007, Merisant France won a significant victory in the Commercial Court of Paris against subsidiaries of McNeil Nutritionals LLC, the American company that markets Splenda. The court awarded Merisant $54,000 in damages and ordered the defendants to cease advertising claims found to violate French consumer protection laws, including the slogans "Because it comes from sugar, sucralose tastes like sugar" and "With sucralose: Comes from sugar and tastes like sugar", giving it four months to comply.[32]

A Sugar Association complaint to the Federal Trade Commission points out that "Splenda is not a natural product. It is not cultivated or grown and it does not occur in nature."[33] McNeil Nutritionals, the manufacturer of Splenda, has responded that its "advertising represents the products in an accurate and informative manner and complies with applicable advertising rules in the countries where Splenda brand products are marketed."[34] The U.S. Sugar Association has also started a web site where they put forward their criticism of sucralose.[35]

Natural alternatives

Critics of sucralose often favor natural alternatives, including xylitol, maltitol, thaumatin, isomalt, stevia and siraitia. However, some natural substances are also accused of causing other potential problems,[36][37][38] and natural products generally do not undergo controlled trials before being allowed in food.[39]

See also

References

- ^ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 8854.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (2006). "Food labeling: health claims; dietary noncariogenic carbohydrate sweeteners and dental caries". Federal Register. 71 (60): 15559–15564.

- ^ Facts About Sucralose, American Dietetic Association, 2006.

- ^ a b c Michael A. Friedman, Lead Deputy Commissioner for the FDA, Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Sucralose Federal Register: 21 CFR Part 172, Docket No. 87F-0086, April 3, 1998

- ^ Browning, Lynnley, "Makers of Artificial Sweeteners Go to Court", New York Times Business section, April 6, 2007

- ^ a b Johnson,Avery, "How Sweet It Isn't", Wall Street Journal, Marketplace Section, April 6, 2007 p.B1

- ^ A Report on Sucralose from the Food Sanitation Council, The Japan Food Chemical Research Foundation

- ^ a b c Sucralose: An Overview, by Genevieve Frank, Penn State University

- ^ Splenda No Calorie Sweetener Fact Sheet, splenda.com

- ^ Extreme Lo-Carb Cuisine: 250 Recipes With Virtually No Carbohydrates, by Sharron Long, ISBN 978-1593370077

- ^ Sweetzfree is a clear liquid syrup base, highly concentrated, and made from 100% pure Sucralose in a purified water concentrate.

- ^ USDA’s Nutrient Data Laboratory

- ^ Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Volume 2, Pg. 95 – 101, Web version here.

- ^ Nutrition Action Health Letter, Center for Science in the Public Interest, May 2008

- ^ Which additives are safe? Which aren't?, Center for Science in the Public Interest

- ^ Diabetes.ca Acceptable daily intake of sweeteners

- ^ FDA Talk Paper T98-16

- ^ FDA Final Rule, Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption; Sucralose

- ^ Everything You Need to Know About Sucralose, International Food Information Council

- ^ Sweeteners & Desserts, American Diabetes Association

- ^ a b Baird, I. M., Shephard, N. W., Merritt, R. J., & Hildick-Smith, G. (2000). "Repeated dose study of sucralose tolerance in human subjects". Food Chemical Toxicology. 38 (Supplement 2): S123–S129. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00035-1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Report from NICNAS, The Australian Government regulator of industrial chemicals (PDF document)

- ^ USFDA Department of Health and Human Services, 1998

- ^ Labare, Michael P.; Alexander, Martin (1993). "Biodegradation of sucralose in samples of natural environments". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 12 (5): 797–804. doi:10.1897/1552-8618(1993)12[797:BOSACC]2.0.CO;2.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Measurements of Sucralose in the Swedish Screening Program 2007, Part I; Sucralose in surface waters and STP samples

- ^ Sötningsmedel sprids till miljön - Naturvårdsverket

- ^ Daniel JW, Renwick AG, Roberts A, Sims J. The metabolic fate of sucralose in rats. Food Chem Tox. 2000;38(S2): S115-S121.

- ^ Natural organochlorines in living organisms: chlorinated compounds, biosynthesized

- ^ Patel, Rajendrakumar M. (2006). "Popular Sweetner Sucralose as a Migraine Trigger". Journal of Head and Face Pain. 46: 1303. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00543_1.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Journal of Mutation Research - August 2002

- ^ Artificial Sweetener Makers Reach Settlement on Slogan, New York Times, May 12, 2007

- ^ Splenda ad slogans banned in France, Food Navigator, May 14, 2007

- ^ Splenda Ads Condemmed as Misleading to Consumers by International Advertising Boards, Sugar Farmers and Processors, Sugar Association Press Release, November 2, 2006

- ^ Sugar industry files complaint over Splenda, Reuters article at MSNBC.com, Nov. 2, 2006

- ^ "The Truth About Splenda" website by the Sugar Association

- ^ Lynch BS, Tischler AS, Capen C, Munro IC, McGirr LM, McClain RM (1996). "Low digestible carbohydrates (polyols and lactose): significance of adrenal medullary proliferative lesions in the rat". Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 23 (3): 256–97. doi:10.1006/rtph.1996.0055. PMID 8812969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nunes AP, Ferreira-Machado SC, Nunes RM, Dantas FJ, De Mattos JC, Caldeira-de-Araújo A (2007). "Analysis of genotoxic potentiality of stevioside by comet assay". Food Chem. Toxicol. 45 (4): 662–6. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2006.10.015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Canimoğlu S, Rencüzoğullari E (2006). "The cytogenetic effects of food sweetener maltitol in human peripheral lymphocytes". Drug Chem Toxicol. 29 (3): 269–78. doi:10.1080/01480540600651600.

- ^ Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994, Public Law 103-417, 103rd Congress

External links

- Tate & Lyle's Official Website for Sucralose

- U.S. FDA Code of Federal Regulations Database, Sucralose Section, As Amended Aug. 12, 1999

- Splenda truth - rebuttal site run by McNeil Nutritionals LLC, makers of Splenda

Science

Press Releases

- FDA press announcement - FDA report on its approval of Splenda

- £97m Investment to Significantly Boost Splenda Sucralose Output (PDF) - describes new manufacturing plant in Singapore