Oglala

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Oglála Lakhóta Oyáte | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 46,855 enrolled tribal members (2013)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Lakota, English[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Sun Dance,[3] Native American Church, Christianity[4] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Lakota peoples, Dakota, Nakota[5] |

The Oglala (pronounced [oɡəˈlala], meaning "to scatter one's own" in Lakota language[5]) are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires). A majority of the Oglala live on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the eighth-largest Native American reservation in the United States.

The Oglala are a federally recognized tribe whose official title is the Oglala Lakota Nation. It was previously called the Oglala Sioux Tribe of the Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota. However, many Oglala reject the term "Sioux" due to the hypothesis (among other possible theories) that its origin may be a derogatory word meaning "snake" in the language of the Ojibwe, who were among the historical enemies of the Lakota. They are also known as Oglála Lakhóta Oyáte.

History

[edit]Oglala elders relate stories about the origin of the name "Oglala" and their emergence as a distinct group, probably sometime in the 18th century.

Conflict with the European settlers

[edit]In the early 19th century, Europeans and American passed through Lakota territory in increasing numbers. They sought furs, especially beaver fur at first, and later bison fur. The fur trade changed the Oglala economy and way of life.

In 1868, the United States and the Great Sioux Nation signed the Fort Laramie Treaty.[6] In its wake, the Oglala became increasingly polarized over how they should react to continued American encroachment on their territory. This treaty forfeited large amounts of Oglala land and rights to the United States in exchange for food and other necessities.[7] Some Lakota bands turned to the Indian agencies — institutions that later served Indian reservations – for rations of beef and subsistence foods from the US government. Other bands held fast to Indigenous lifeways. Many Lakota bands moved between these two extremes, coming in to the agencies during the winter and joining their relatives in the north each spring. These challenges further split the various Oglala bands.

The influx of white settlers into the Idaho Territory often meant passing through Oglala territory, and, occasionally, brought with it its perils, as Fanny Kelly described in her 1871 book, Narrative of My Captivity among the Sioux Indians.[8]

Early reservation

[edit]The Great Sioux Reservation was broken up into five portions. This caused the Red Cloud Agency to be moved multiple times throughout the 1870s until it was relocated and renamed the Pine Ridge Reservation in 1878. By 1890, the reservation included 5,537 people, divided into a number of districts that included some 30 distinct communities.

2022 temporary Christian missions suspension

[edit]In July 2022, the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council effected a temporary suspension of Christian missions on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The council called for an investigation into the financial practices of the Dream Center Missionary, and the Jesus is King Mission was ejected from the reservation for spreading pamphlets that the tribe saw as hateful.[9]

Social organization

[edit]

The respected Oglala elder Left Heron once explained that before the coming of the White Buffalo Calf Woman, "the people ran around the prairie like so many wild animals," not understanding the central importance of community. Left Heron emphasized that not only did this revered spirit woman bring the Sacred Pipe to the tribe but she also taught the Lakota people many valuable lessons, including the importance of family (tiwahe) and community (tiyospaye). The goal of promoting these two values then became a priority, and in the words of Dakota anthropologist Ella Cara Deloria, "every other consideration was secondary—property, personal ambition, glory, good times, life itself. Without that aim and the constant struggle to attain it, the people would no longer be Dakotas in truth. They would no longer even be human."[11] This strong and enduring connection between related families profoundly influenced Oglala history.

Community (Tiyóšpaye)

[edit]Dr. John J. Saville, the U.S. Indian agent at the Red Cloud Agency, observed in 1875 that the Oglala tribe was divided into three main groups: the Kiyuksa, the Oyuĥpe and the True Oglala. "Each of these bands are subdivided into smaller parties, variously named, usually designated by the name of their chief or leader."[12] As the Oglala were settled on the Pine Ridge Reservation in the late 1870s, their communities probably looked something like this:

Oyuȟpe Tiyóšpaye

Oglala Tiyóšpaye

- True Oglala

- Caŋkahuȟaŋ (He Dog's band). Other members include: Short Bull; Amos Bad Heart Bull.

- Hokayuta (Black Twin's band)

- Huŋkpatila (Little Hawk and Crazy Horse's band)

- Ité šíčA (Red Cloud's band)

- Payabya (They Even Fear His Horses's band)

- Wagluȟe (Chief Blue Horse, American Horse and Three Bear's band)

Kiyaksa Tiyóšpaye

- True Kiyaksa

- Kuinyan (Little Wound's band)

- Tapišleca (Yellow Bear's band)

Population

[edit]By 1830, the Oglala had around 3,000 members. In the 1820s and 1830s, the Oglala, along with the Brulé, another Lakota band, and three other Sioux bands, formed the Sioux Alliance. This Alliance attacked surrounding tribes for territorial and hunting reasons.

Culture

[edit]Gender roles

[edit]Historically, women have been crucial to the family's life: making almost everything used by the family and tribe. They have cultivated and processed a variety of crops; prepared the food; prepared game and fish; worked skins to make clothing and footwear, as well as storage bags, the covering of tipis, and other items. Women have historically controlled the food, resources and movable property, as well as owned the family's home.[13]

Typically, in the Oglala Lakota society, the men are in charge of the politics of the tribe. The men are usually the chiefs for political affairs, war leaders and warriors, and hunters. Traditionally, when a man marries, he goes to live with his wife with her people.

Oglala flag

[edit]

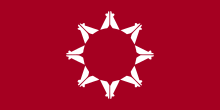

The Oglala flag's red field symbolizes the blood shed by the Sioux in defense of their lands and the very idea of the "red men". A circle of eight white tepees, tops pointing outward, represents the eight districts of the reservation: Porcupine, Wakpammi, Medicine Root, Pass Creek, Eagle Nest, White Clay, LaCreek, and Wounded Knee (FBUS, 260-262). When used indoor or in parades, the flag is decorated with a deep-blue fringe to incorporate the colors of the United States into the design.".[14]

"The flag was first displayed at the Sun Dance ceremonies in 1961 and officially adopted on 9 March 1962. Since then it has taken on a larger role, perhaps because of its age, clear design, and universal symbolism. The Oglala flag is now a common sight at Native American powwows, not just Sioux gatherings, and is often flown as a generic Native American flag."[15]

The flag pictured is the original not the current OST Flag.

Notable Oglala

[edit]

Leaders

[edit]- American Horse (The Younger)

- American Horse (The Elder)

- Ohitika (Brave)

- Bryan Brewer

- Crazy Horse

- Crow Dog (Kangisanka)

- Kicking Bear

- Little Wound

- Old Chief Smoke (Šóta)

- Red Cloud

- Iron Tail

- Flying Hawk

- Big Mouth

- Cecilia Fire Thunder

- Theresa Two Bulls

- They Even Fear His Horses (Tȟašúŋke Kȟokípȟapi)

- Black Elk

- Red Shirt (Oglala)

- Luther Standing Bear

- Henry Standing Bear

- Russell Means (Oyate Wacinyapin)

- John Yellow Bird Steele

- Steve Livermont

Military personnel

[edit]- Ed McGaa – Korean and Vietnam War veteran

- Ola Mildred Rexroat – WASP, World War II[16]

Artists

[edit]- Imogene Goodshot Arquero, beadwork artist

- Arthur Amiotte, mixed-media artist

- Amos Bad Heart Bull

- Kicking Bear, ledger artist

Poets

[edit]Storytellers

[edit]Lame Deer - Medicine Man https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Fire_Lame_Deer

Athletes

[edit]- Billy Mills, Olympic champion (1964)

- Teton Saltes, professional football player signed by the New York Jets of the NFL (2021)

- SuAnne Big Crow, basketball player for Pine Ridge High School

Performers

[edit]- Albert Afraid of Hawk – member of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show who died and was buried in Danbury, Connecticut, while on tour in 1900. His remains were exhumed and re-interred on Pine Ridge Reservation in 2012.[17]

Culinary activists

[edit]See also

[edit]- Sicaŋǧu, Brulé (Burned Thighs)

- Itazipco, Sans Arc (No Bows)

- Huŋkpapa (End of Village)

- Miniconjou (Swamp Plant)

- Sihasapa (Blackfoot Sioux)

- O'ohenuŋpa (Two Kettles)

- Four Guns

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Pine Ridge Agency." Archived 2013-02-17 at the Wayback Machine US Department of the Interior Indian Affairs. Retrieved 25 Feb 2013.

- ^ Pritzker 329

- ^ Pritzker 331

- ^ Pritzker 335

- ^ a b Pritzker 328

- ^ Soulek, Lauren (January 12, 2024). "Native American treaty law 101". KELOLAND. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Means, Jeffrey D. (Autumn 2011). "'Indians SHALL DO THINGS in Common': Oglala Lakota Identity and Cattle-Raising on the Pine Ridge Reservation". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 61 (3): 3–21, 91–93. JSTOR 23054756.

- ^ Fanny Kelly on her captivity among the Sioux Indians, Narrative of My Captivity Among the Sioux Indians by Fanny KELLY read by Tricia G. | Full Audio Book on YouTube, LibriVox Audiobooks.

- ^ Thompson, Darren (July 28, 2022). "Oglala Sioux Tribe Temporarily Suspends All Christian Missionary Work". Native News Online. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ "Get Involved: Sarah Eagle Heart on How to Support Native Communities". Voices Magnified. A&E. March 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ Deloria, Ella (1944). Speaking of Indians. New York: Friendship Press. p. 25.

- ^ Saville, John J. (August 31, 1875). "To Commissioner of Indian Affairs". Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Indian Affairs, Government Printing Office: 250. Dr. Saville also listed a fourth band, the Wajaje, in his report, but while they were closely associated with the Oglala at that time, they were in fact Brulé.

- ^ LaFromboise, Teresa D.; Heyle, Anneliese M.; Ozer, Emily J. (1990). "Changing and diverse roles of women in American Indian cultures". Sex Roles. 22 (7–8): 455–476. doi:10.1007/bf00288164. S2CID 145685255.

- ^ [1], CRW Flags

- ^ [2], CRW Flags

- ^ "American Indian Heritage Month – Native American Women Veterans". Department of Defense.

- ^ "Albert Afraid of Hawk". Albert Afraid of Hawk. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Sioux Chef". The Sioux Chef. Retrieved January 13, 2019. From website ("Sean Sherman: Founder / CEO Chef"): "The Sioux Chef team continues with their mission statement to help educate and make indigenous foods more accessible to as many communities as possible."

References

[edit]- Oglala Sioux Tribe: A Profile

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Ruling Pine Ridge: Oglala Lakota Politics from the IRA to Wounded Knee Texas Tech University Press

- Black Elk Speaks: Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux University of Nebraska Press