Tautog

| Tautog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Labriformes |

| Family: | Labridae |

| Genus: | Tautoga Mitchill, 1814 |

| Species: | T. onitis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tautoga onitis (Linnaeus, 1758)

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Genus:

Species:

| |

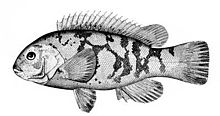

The tautog (Tautoga onitis), also known as the blackfish, is a species of wrasse native to the western Atlantic Ocean from Nova Scotia to South Carolina. This species inhabits hard substrate habitats in inshore waters at depths from 1 to 75 m (5 to 245 ft). It is currently the only known member of its genus.[2]

Barlett (1848) wrote, "[Tautaug] is a Native American word, and may be found in Roger Williams' Key to the Indian Language." The name is from the Narragansett language, originally tautauog (pl. of taut). It is also called a "black porgy" (cf. Japanese black porgy), "chub" (cf. the freshwater chub), "oyster-fish" (in North Carolina) or "blackfish" (in New York/New Jersey, New England).

Description

[edit]Tautog are brown and dark olive, with white blotches, and have plump, elongated bodies. They have a typical weight of 0.5 to 1.5 kg (1 to 3 lb) and reach a maximum length and weight of 90 cm (3 ft) and 13.1 kg (28 lb 14 oz), respectively.

Tautog have many adaptations to life in and around rocky areas. They have thick, rubbery lips and powerful jaws. The backs of their throats contain a set of teeth resembling molars. Together, these are used to pick and crush prey such as mollusks and crustaceans. Their skin also has a rubbery quality with a heavy slime covering, which helps to protect them when swimming among rocks.[3]

Cuisine

[edit]Goode (1884) said, "The tautog has always been a favorite table fish, especially in New York, its flesh being white, dry, and of a delicate flavor."[4]

Davidson recommends grilling, baking, and using it in fish chowder.[5]

Sports fishing

[edit]Popular among fishermen, tautog have a reputation for being a particularly tricky fish to catch. Part of this is because of their tendency to live among rocks and other structures that can cause a fisherman's line to get snagged. The favorite baits for tautog include green crabs, Asian shore crabs, fiddler crabs, clams, shrimp, mussels, sandworms, and lobsters. Tautog fishing may also be difficult due to the tendency of fishermen to try to set the hook as soon as they feel a hit, rather than waiting for the tautog to swallow the bait. Rigs with minimal beads, swivels, and hooks should be used to prevent entanglement with the rocks, reefs, or wrecks that tautog frequent.[citation needed]

Because they are found in wrecks, they are often seen by scuba divers. They are also popular with spearfishermen.[citation needed]

Life cycle

[edit]

Spawning occurs offshore, in late spring to early summer. The eggs hatch and develop while drifting. All of the young take residence in shallow, protected waters and live and hide in seaweed, sea lettuce, or eelgrass beds for protection, and are green in color to camouflage themselves. During the late fall, they move offshore and winter in a state of reduced activity.

Management

[edit]Slow reproduction and growth make tautog more vulnerable to overfishing. The species is managed by focusing on reducing fishing mortality rates, as well as restrictions on gear, size limits, possession limits, and limited fishing seasons. At present, the Blue Ocean Institute recommends that consumers avoid eating this fish because the populations are at low levels that are not considered sustainable.[6]

Around 1920, 750 tons were harvested annually off the New England coast.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Choat, J.H.; Pollard, D. (2010). "Tautoga onitis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010: e.T187479A8547027. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T187479A8547027.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Tautoga onitis". FishBase. October 2013 version.

- ^ McClane, A.J., McClane's Field Guide to Saltwater Fishes of North America, 1978, ISBN 0-8050-0733-4

- ^ G. Brown Goode, et al., The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, 1884-7, quoted in Davidson, 1979.

- ^ Alan Davidson, North Atlantic Seafood, 1979, ISBN 0-670-51524-8.

- ^ "Tautog". Seafood Choices. Blue Ocean Institute. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

External links

[edit]- Dixon, M. S. "The Use of SCUBA and Punctuated Transects to Count a Temperate Reef Fish". In: Maney, E. J. Jr. & Ellis, C. H. Jr. (Eds.) the Diving for Science...1997. Seventeenth annual Scientific Diving Symposium. Northeastern University, Boston, MA: Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS). Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.