The Broken Column

| The Broken Column | |

|---|---|

| Spanish: La Columna Rota | |

| |

| Artist | Frida Kahlo |

| Year | 1944 |

| Type | Oil on masonite |

| Dimensions | 39.8 cm × 30.6 cm (15.7 in × 12.0 in) |

| Location | Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico City, Mexico |

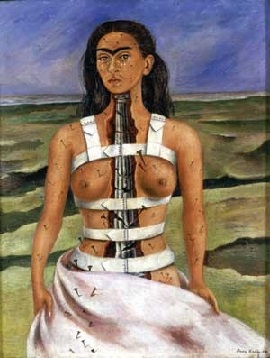

The Broken Column (La Columna Rota in Spanish) is an oil on masonite painting by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, painted in 1944 shortly after she had spinal surgery to correct on-going problems which had resulted from a serious traffic accident when she was 18 years old. The original is housed at the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Xochimilco, Mexico City, Mexico.[1]

As with many of her self-portraits, pain and suffering is the focus of the work,[2] though unlike many of her other works, which include parrots, dogs, monkeys and other people,[3] in this painting, Kahlo is alone. Her solitary presence on a cracked and barren landscape symbolizes both her isolation[2] and the external forces which have impacted her life. As an earthquake might fissure the landscape, Kahlo's accident broke her body.[4]

In the painting Kahlo's nude torso is split, replicating the ravine-laced earth behind her and revealing a crumbling, Ionic column in place of her spine. Her face looks forward, unflinchingly, though tears course down her cheeks. In spite of the brokenness of her internal body, her external sensuality is unmarred. The cloth which wraps the lower part of her body and is grasped in her hands, is not a sign of modesty[4] but instead mirrors the Christian iconography of Christ's sheet, as do the nails which are piercing her face and body.[5] The nails continue down only her right leg which was left shorter and weaker from contracting polio as a young child.

The metal corset, which depicts a polio support, rather than a surgical support,[6] may refer to her history of polio[3] or symbolize the physical and social restrictions of Kahlo's life.[4] By 1944, Kahlo's doctors had recommended that she wear a steel corset instead of the plaster casts she had worn previously. The brace depicted is one of many that Frida actually used throughout her life time and is now housed in her home and museum, Casa Azul.[7] In The Broken Column this corset holds together Kahlo's damaged body.[5][8][9]

Kahlo as a martyr

[edit]

One can draw a parallel from Kahlo’s portrayal of herself to that of the “Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian.”[10] In Sebastian's legend, he was discovered to be a Christian and tied to a tree and used as an archery target. Despite being left for dead he survives, only to later perish for his religion by the hands of the Imperial Roman. He is often portrayed tied to a tree, body littered with arrows. The American poet Bruce Bond writes, “pain is an arrow that pins a body to the bone” in a 2013 poem named after the Saint.[11] Frida aligns herself with the martyr visually, and being raised in a Catholic home she would have been familiar with the patron saint of soldiers.

Desmond O’Neill, a physician writing for the British Medical Journal, describes Frida’s work as a vital tool in the understanding of pain in patients. The doctor commends Frida’s ability to portray the intangible feeling of chronic pain. In this way she becomes a martyr for those plagued by chronic pain. In her willingness to bare her soul to the viewer allows for a greater understanding of what it means to live with constant and intense pain. Though pain is all around us we lack the ability to “grasp or express it,” Frida Kahlo is the exception to the problem of portraying pain.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Stavans, Ilan. "Art: The Broken Column". Annenberg Learner. St. Louis, Missouri: Annenberg Foundation. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b Finger et al. 2013, p. 246.

- ^ a b Griffiths, Jay (26 March 2014). "Frida Kahlo: a life of hope and defiance". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Lindauer 2011, p. 68.

- ^ a b Kettenmann 2000, p. 67.

- ^ Collins, Amy Fine (3 September 2013). "Diary Of A Mad Artist". New York City, New York: Vanity Fair. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Kardos, "Casa Azul," A City A Month.

- ^ Staff writer. "Frida Kahlo: Room Guide: Room 11: Achieving Equilibrium". Tate Modern. Tate Modern. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Grosenick, Uta, ed. (2001). Women artists in the 20th and 21st century. Köln: Taschen. p. 252. ISBN 9783822858547.

- ^ a b O’Neill, The Broken Column, 1031.

- ^ Bond, "Saint Sebastian," 679.

Sources

[edit]- Bond, Bruce. "Saint Sebastian." The Southern Review, no. 4 (2013): 679.

- Finger, Stanley; Zaidel, Dahlia W.; Boller, Françoise; Bogousslavsky, Julien (2013). The Fine Arts, Neurology, and Neuroscience: Neuro-Historical Dimensions. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-62736-0.

- Kardos, Michael. "Casa Azul - Frida Kahlo's Home." A City a Month. Last modified November 15, 2015. http://acityamonth.com/casa-azul-frida-kahlos-home-for-life/.

- Kettenmann, Andrea (2000). Frida Kahlo, 1907-1954: Pain and Passion. Hohenzollernring, Germany: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5983-4.

- Lindauer, Margaret A. (2011). Devouring Frida: The Art History and Popular Celebrity of Frida Kahlo. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-7209-7.

- O’Neill, Desmond. “The Broken Column by Frida Kahlo.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 342, no. 7805 (May 7, 2011): 1031.